Rastee Chaudhry

Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

Blog

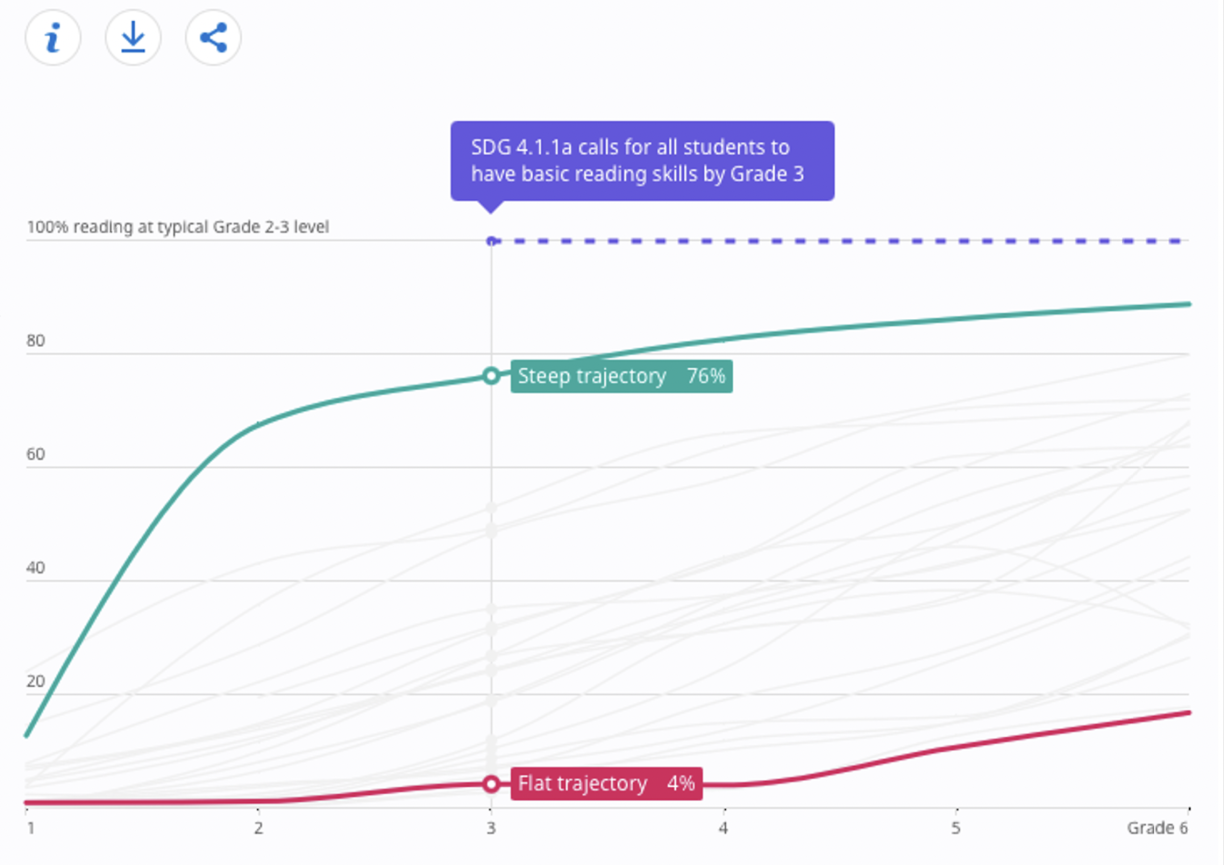

Learning trajectories are graphs that show how many children achieve a certain level of minimum proficiency at each grade. While learning trajectories have previously been used for research, two new efforts show that they can also serve as practical tools to analyse the learning crisis and take informed action.

First, the Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) Programme, in partnership with the GEM Report, have created a webpage offering a one-stop resource on learning trajectories. This webpage introduces learning trajectories and what they offer through a series of interactive data visualisations and a data explorer which allows users to build and analyse their own learning trajectories. Second, RISE and the Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa (CSEA) have partnered to train around 75 policymakers and government officials in West Africa on the use of learning trajectories for informed policymaking.

This online tool, which shows the learning trajectories for 23 low- and lower-middle-income countries is part of the SCOPE website and was launched at the ADEA 2022 Triennale. It shows the percentage of children in each grade who have mastered foundational reading or mathematics skills, typically at grade 2 or 3 level, which roughly correspond to Sustainable Development Goal indicator 4.1.1a.

Unlike conventional ways of assessing learning, which measure skills students have acquired at a certain point in time (e.g., end of primary school), learning trajectories track how many children achieve a minimum standard at each grade to offer key insights into the process of learning.

What are the key insights from these trajectories?

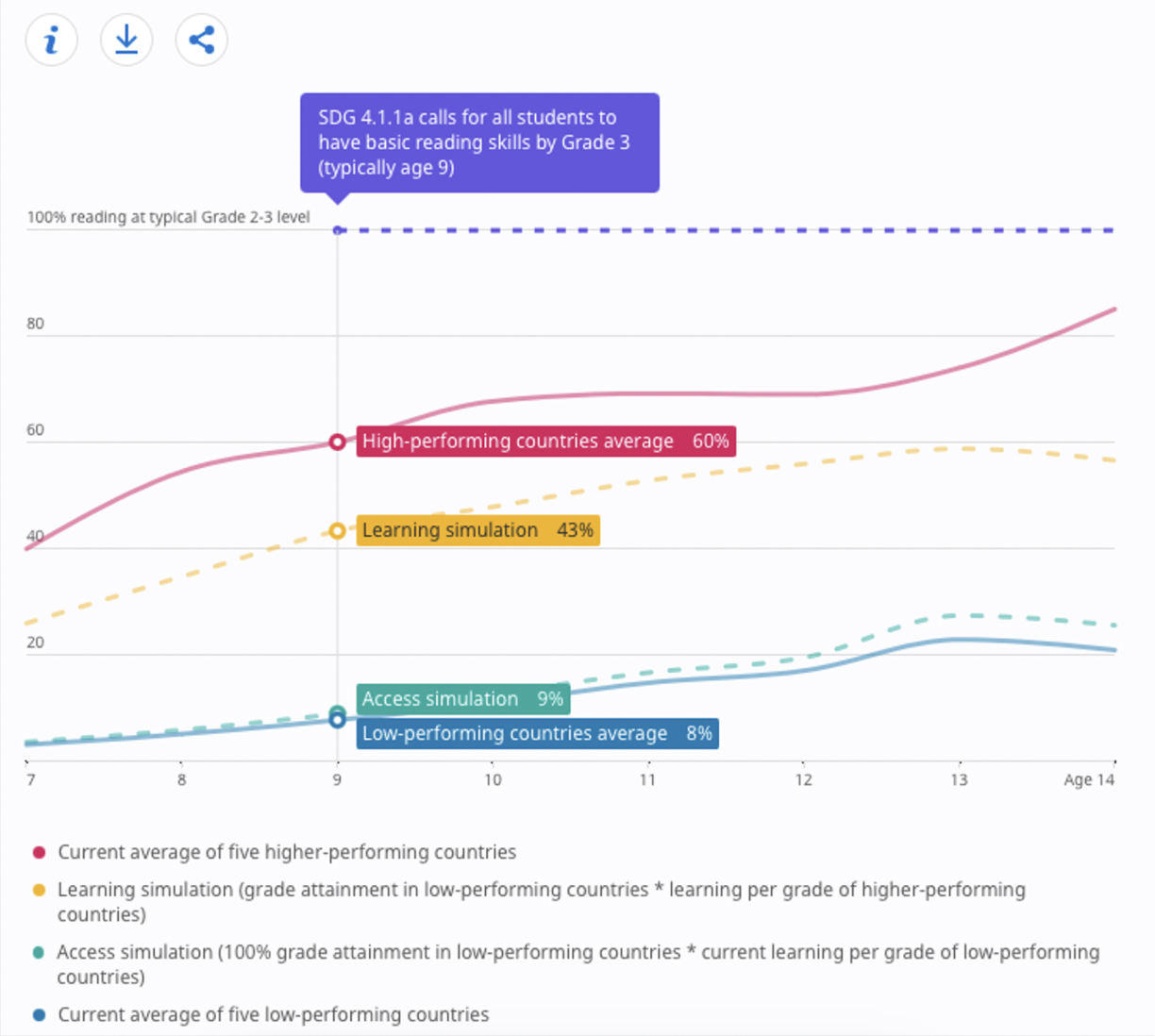

The tool simulates the impact of pursuing different high-level policy agendas in different countries. The first simulation compares the impact of access-oriented policies (green dotted line), and learning-oriented policies (yellow dotted line).

It shows that:

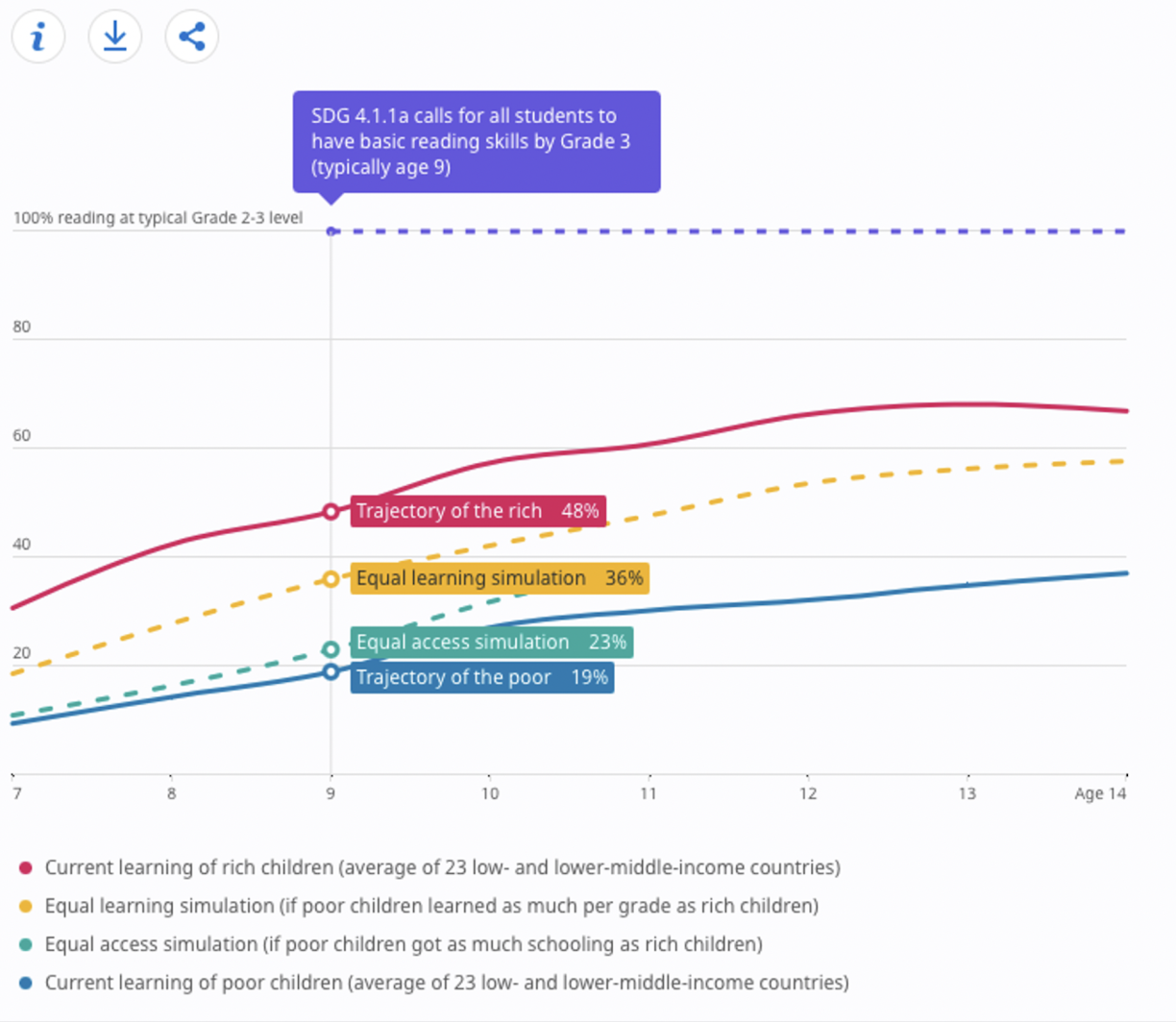

The second simulation compares the impact of equity-oriented policies. It shows that while policies aimed at increasing equity are important, they will do little to resolve the learning crisis.

Users can create their own trajectories on the SCOPE website and run policy simulations using actual data for countries of their choice. The data explorer has data on foundational reading and mathematics for 31 countries and 6 demographic groups per country (rich/ poor, boys/girls, urban/rural), sourced from the UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey. Bespoke graphs and simulations can be exported as images or datasets and shared on social media.

Over the past year, researchers from RISE and CSEA have implemented three iterations of a capacity development training based on learning trajectories, twice in Abuja and once in Accra. Each training had around 25 participants, which included government officials, school administrators, teachers, and education NGO practitioners. The two-day training focused on an overview of the global learning crisis, the host country context, learning trajectories and their use, and two tools:

Learning trajectories can support non-researchers in better understanding the learning crisis and in informing policy design. The training has:

I would improve on my formative assessment in my school and capture data to support any deductions we will be making henceforth about the extent of learning that is taking place.” – School administrator from Nigeria

“Modelling helps provide a better graphical representation of real issues or pertinent situations. In this regard, policymakers and influencers could make meaning and be armed with informed backgrounds in order to make needful informed sessions.” – Policymaker from Ghana

“Lessons from the training will help me to contribute to policy issues on how to balance access and learning outcomes through curriculum development.” – Policymaker from Nigeria

“The tools will help me and my institution collect data for education interventions and analysis. I learnt that there is a need to pay attention to learning achievement rather than years of schooling.” – Policymaker from Ghana

To learn more about learning trajectories, the new online tool, and the different use cases of learning trajectories, join an upcoming webinar by GEM and RISE on December 6th 2022.

This blog was originally published on World Education Blog on 10 November and has been re-posted with permission.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.