Amare Asgedom

Addis Ababa University

Insight Note

- Both federal government and donor stakeholders have had a high level of involvement in the design process of General Education Quality Improvement for Equity (GEQIP-E), with their priorities generally converging. However, these stakeholders acknowledge that it has generally been a top down process, with more limited engagement and knowledge at the woreda (district) and school level.

- The increased focus on equity in GEQIP-E has been welcomed by both government and donor stakeholders, and is seen to reflect the priorities of both groups. However, questions were raised as to whether the approach is expansive enough to bring about meaningful improvements in equity.

- The new Performance for Results (PforR) financing approach designed to strengthen the education system has been received with a mixture of optimism and scepticism amongst stakeholders, with identified barriers - including the lack of sufficient knowledge amongst those implementing GEQIP and the perceived inflexibility of the approach.

Education has remained high on the agenda of the Ethiopian government, with the 1994 Education and Training Policy setting out a transformative approach for the education sector. This included a focus on access and quality, both with an equity perspective. Since this time, primary school access has expanded rapidly in Ethiopia, increasing threefold over a 20 year period. More recently, the considerable and sustained commitment of the government to improving education quality is reflected in its investment in the General Education Quality Improvement Programme (GEQIP). The GEQIP programme has been implemented since 2008, with the third and current round (2018-2022) having an explicit focus on equity, namely that it aims to ensure that all children in Ethiopia have the opportunity to reach their full potential and achieve at least a basic level of good quality education, no matter their gender, family background, or disability status (Box 1).

Despite the continued efforts of the government and donor stakeholders, low learning levels present a major challenge, with huge numbers of students leaving school without having acquired basic skills in reading, writing, and numeracy. In addition, meaningful improvements have been particularly slow for disadvantaged groups, many of whom remain out of school (particularly girls), children with disabilities, and children from pastoralist communities. Questions have been raised as to why the quality of education has remained so poor and learning levels remain low despite the early and sustained commitment of the government and other stakeholders to education quality in Ethiopia.

Since February 2018, the RISE Ethiopia research team has been undertaking a system diagnostic of the education system with relation to GEQIP, coinciding with the end of GEQIP-II and the beginning of GEQIP-E. An important part of this system diagnostic is understanding how the design of the GEQIP reforms in particular might have affected slow progress in quality and learning. The system diagnostic has involved analysis of government policy, plans, and programme, and actor mapping, which has informed key stakeholder interviews. The key informant interviews, which took place between February and December 2018, were conducted with 184 donors and government officials (Table 1). Government officials included individuals from the Ministry of Education (MoE) and the Ministry of Finance (MoF) at the different levels of the Ethiopian education system, including the federal, regional, and woreda (district) level, across the seven regions in Ethiopia that are included in the RISE research.1 Donors interviewed included those who provide financial and/or technical assistance to GEQIP. Interviews were conducted in the preferred language of the participants where possible, and interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed. Thematic analysis was used to code the data, facilitated by NVivo software.

The General Education Quality Improvement Programme for Equity (GEQIP-E) (2018-2022) is the third phase of the Ethiopian Government’s largest education quality reform programme, designed to support the government’s existing education policy and plans. It is funded by multiple donors including the World Bank, the Department for International Development (DFID), the Embassy of Finland, and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The main goal of GEQIP-E is to improve student learning outcomes by improving the quality of education with an explicit focus on equity, building on the strengths and challenges of previous phases of the reforms. The scope of the current phase of GEQIP-E has shifted in three main ways:

Table 1: Stakeholders included in the RISE Ethiopia System Diagnostic

| Stakeholder Group | Organisations/Offices | No. | |

|---|---|---|---|

Stage 1, Feb 2018 |

Federal Level Government Donors/Development Partners |

Directorates in the Ministry of Education (MoE); Ministry of Finance (MoF) World Bank; DFID; Finland; USAID; JICA; Norway; UNICEF |

29 17 |

| Stage 2, May 2018 | Regional Level and Zonal (Addis Ababa, Amhara, Afar, Benishangul-Gumuz, Oromia, SNNPR, Somali) | Experts from Regional Education Bureaus; Regional Finance Bureau; Colleges of Teacher Education and Centres of Excellence | 66 |

| Stage 3, Dec 2018 | Woreda Level (RISE survey sites in each region) | Woreda Education Offices; Woreda Finance Offices; schools | 72 |

As a follow up to the interviews, in February 2019, the RISE Ethiopia team brought together key stakeholders in two dialogue workshops, aimed at exploring emerging insights from the ongoing analysis of data from the RISE Ethiopia system diagnostic. One workshop was held with federal and regional government stakeholders (23) and one was held for donors (7) who are involved in the GEQIP-E programme. The majority of the workshop participants had also participated in the key stakeholder interviews. The workshops provided the opportunity to triangulate findings from the interviews (especially where there were divergences in views emerging in the data), to help to inform the ongoing data analysis and to contribute to subsequent recommendations that emerge from this study, ensuring that they are relevant for stakeholders working in the education system.

This paper draws on data from the interviews and workshops with stakeholders to address the following questions:

A mapping exercise was undertaken to identify who the main actors are in relation to GEQIP, including donors, government officials, and local level stakeholders (including school principals, teacher, students, and parents). The actor mapping was an iterative process and, from the initial broad list of actors, we identified those who are most relevant to the GEQIP-E reforms and their roles and responsibilities in relation to this programme (Table 2).

Table 2: Roles and Responsibilities of Key Actors within the Education System

| Actor | Main Responsibilities in Relation to GEQIP-E |

|---|---|

| World Bank | Overall programme coordination, providing financial assistance (FA) and technical assistance (TA). |

| DFID | Pool partner. Provide TA. |

| Embassy of Finland | Pool partner. Provide TA. |

| UNICEF | Pool partner. Provide TA. |

| USAID | Pool partner. |

| Norway | Pool partner. |

| JICA | Provide TA. |

| Italian Cooperation for Development | Pool partner in GEQIP II. |

| Ministry of Finance (Channel One Programmes Coordination Directorate) | Responsible for financial coordination of the programme and consolidation of the financial reports. |

| Ministry of Education (MoE) | Responsible for overall coordination of the Programme as well as providing overall leadership and guidance. |

| Programme Steering Committee, MoE | Oversee coordination and monitoring to verify progress of the implementation of the programme. |

| Planning and Resource Mobilisation Directorate (PRMD), MoE | Implementing agency of the Programme, responsible for the overall implementation of the programme. |

| Other directorates and agencies, MoE | Will coordinate programme activities and support the PRMD in the planning, management, monitoring and reporting on the programme implementation. |

| Regional Education Bureau (REB) | Responsible for coordinating and implementing the programme at the regional level, and are responsible for the overall quality and timeliness of the programme implementation in their respective jurisdictions. |

| Bureau of Finance and Economic Development (BoFED) | In close coordination with REBs, will be responsible for financial coordination in the region. |

| Woreda Education Office | Responsible for implementing the programme at the woreda level. Responsible for monitoring the programmes implementation in schools and reporting to REBs. |

| Woreda Finance Office | Responsible for implementing the programme at the woreda level. |

| School | Responsible for implementing the programme at the woreda level. Programme beneficiaries. |

| Teachers | Programme beneficiaries. |

| Parents | Programme beneficiaries. |

| Students | Programme beneficiaries. |

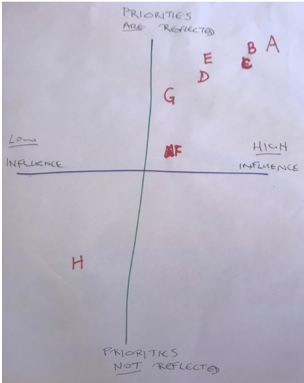

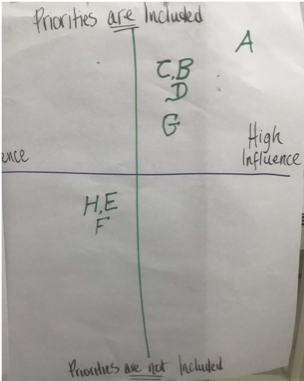

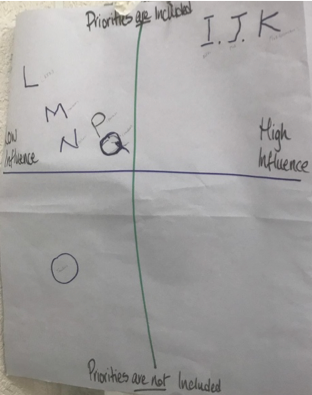

The design of GEQIP-E was coordinated by the Planning and Resource Mobilisation Directorate at the Ministry of Education with close support from the World Bank. During interviews, it was identified that multiple federal government and donor stakeholders took part in the design process and reported having a high level of participation in the design process, albeit to varying degrees, and their priorities were perceived as being included in GEQIP-E. During the stakeholder dialogue workshops, this was explored further through a mapping exercise with groups of donors and government officials separately (see Figure 1 for the mapping exercise).

Overall, both the government and donors expressed having strong ownership of GEQIP-E, although with some variation. Both government officials and donors identified donors as having a high level of influence in the design process of GEQIP-E, and their priorities were generally viewed by both groups to have been well reflected in GEQIP-E. Amongst donors, the level of influence and degree to which their priorities were included varied somewhat. There was broad agreement that the World Bank had the highest level of influence, followed by the Department of International Development (DFID) and the Embassy of Finland. Other donors, including Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and the Italian Agency for Cooperation and Development, were perceived as having lower levels of influence in the design process (Figure 2 a-c). To some extent, this pattern reflects the extent of financial contribution to GEQIP-E, with the World Bank and DFID being the largest contributors. Even so, it is worthwhile noting that while Finland is a smaller contributor, it has had important influence in the inclusion of disability within GEQIP-E.

Critically reflecting on their own processes, donors viewed that government stakeholders had less influence than they did in the design process of GEQIP-E, although their priorities were largely seen as being reflected in the design of GEQIP-E (Figure 3a-c). One donor suggested that this disparity is due to the fact that donors are in control of finance:

“The biggest influence is supposed to be the Ministry of Education. But we also know that the ones who dig deeper into their pockets sometimes have a real final say.” - donor representative

This was also perceived to be the case amongst some government officials, as described by one stakeholder from the Ministry of Education:

“We are [a] very poor country. We need every single penny to be used for the intended purpose. So we accept all, as a government. That has to be handled as, you know […] the Ministry of Education is co-chairing the Working Group and has to balance the interventions coming from the World Bank, DFID and other donors.” - federal government representative

More generally, however, government stakeholders had the view that they did have a strong influence over the process, more so than donors appeared to realise, although this varied amongst the different types of government officials.

In terms of different government stakeholders, the Ministry of Finance (MoF) was identified as having the highest level of influence by both government and donors. High levels of influence were also attributed to the Ministry of Education (MoE), particularly the Planning and Resource Mobilisation Directorate. Other directorates within the Ministry of Education were viewed as having a slightly lesser influence, but an important influence nonetheless. One donor representative described how the high level of participation of the government was a necessary precondition to their support of the GEQIP programme:

“The role of the Ministry [of Education] is that they are the most important partner, and if they were not the most important partner to the World Bank, we wouldn’t support it; because this is our way of working directly with the government, instead of having a bilateral agreement.” - donor representative

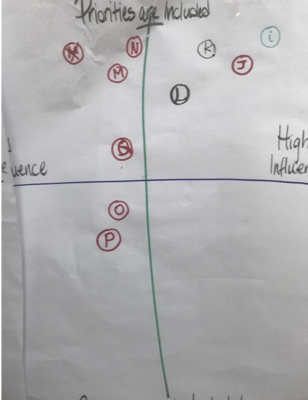

A particular shortcoming of the design process of GEQIP-E identified by donors and government stakeholders at federal and regional levels of the system was the top-down nature in which it occurred. Efforts were made by the Ministry of Education and donors to consult regional and woreda level stakeholders during the design process, including a number of consultation and validation workshops. However, a few individual stakeholders, at the regional level in particular, felt that these consultations did not have a large impact on the design:

“In the Regional Education Bureau, they consulted only selected groups.” - regional government stakeholder

“No one has participated in the design process from this region. After [GEQIP-E] is designed we were invited to a workshop to familiarize us with GEQIP-E…but the design was already prepared by consultants and we were invited to the workshops. We gave comments on issues which are not considered in the design and which are not emphasised.” - regional government stakeholder

Local level stakeholders - including the woreda education bureau, schools, teachers, parents, and students – were identified by all as having the lowest level of influence in the design of GEQIP-E. In particular, teachers and parents were seen as having extremely limited involvement, which both government and donor stakeholders saw as a cause for concern for successful implementation. With respect to the woreda education bureau officials and students, while they were seen to have low influence, government officials indicated that they felt their priorities were included in the GEQIP-E design. This could be because federal and regional representatives considered that priorities at woreda and student levels were aligned with theirs.2

Finally, it is of interest to note that, across all of the groups, none identified either government or donor stakeholders who had high influence not having their priorities included – as such, influence did appear to be important.

According to the stakeholders interviewed, key shifts that have occurred in GEQIP-E, namely the increased focus on equity and the inclusion of PforR financing, have been influenced by a number of factors (Table 3). This includes a combination of international and national priorities. At the international level, both government and donor stakeholders referred to the Sustainable Development Goals as a motivation for the equity focus. At the national level, GEQIP-E priorities were viewed by federal government and donor stakeholders as being aligned with the fifth Education Sector Development Plan. With respect to the shift towards payment for results, both donors and government officials suggested that this occurred as a result of the need to address problems and challenges of previous phases of GEQIP. Interestingly, they each viewed that they suggested the approach (with MoF in particular proposing this from the government perspective).

Table 3: Stakeholder perspectives of factors influencing the design of GEQIP-E

| Equity Focus | Programme for Results (PforR) | |

|---|---|---|

| Donor |

|

|

| Federal Government |

|

|

| Regional |

|

*Italics represent the common perceived factors identified across donor and federal government stakeholders

In GEQIP-E, explicit focus is given to issues of equity, including for girls, children with disabilities, and children living in pastoralist communities. Both donors and government officials at all levels of the education system welcome the increased focus on equity in GEQIP-E which they saw as reflecting their priorities, although some stakeholders had influence over particular aspects. For example, the increased focus on children with disabilities was largely seen to have been driven by the Embassy of Finland (one of the smaller financial contributors to GEQIP-E), who have had a long-term interest in supporting this area in Ethiopia. At the same time, the government indicated that the equity focus reflected the priorities of the government outlined in the Education Sector Development Plans (ESDPs). For example, education for children with disabilities has also been a continuing priority of the government as outlined in these plans.

Although both donors and federal government officials were in agreement of the need to prioritise equity issues, there was less consensus (both within and between these groups) regarding how this should be done. For example, while there was broad agreement amongst stakeholders that there was a need to focus on marginalised groups, there was less agreement on how this should be achieved. One area of contention was school feeding, which was not ultimately included in GEQIP-E. Government stakeholders at all levels of the system (federal, regional and woreda) emphasised the importance of school feeding for supporting children from poor families citing it as an important factor in attracting students to pre-primary school (O-Class) and as a major protective factor against school dropout, particularly in climate vulnerable locations. However, ultimately the decision came down to donors who were funding the programme and considered the school feeding programme as too expensive. Another challenge described by some donors, was that the government was more concerned about geographical equality (i.e., giving the same to all) rather than equity (i.e., giving more to those who need the most):

“I think that there was focus on equity in Ethiopia, which was doing the same thing everywhere. That was an Ethiopian sense of equity . . . doing the same in all the regions." - donor representative

This was identified by donors as a barrier to identifying effective interventions at the grassroots level.

In terms of girls’ education, GEQIP-E focuses on girls’ upper primary education (Grades 5-8) in the emerging regions (Afar, Benishangul Gumuz, and Somali). Interventions to improve girls’ education include the empowerment of girls through girls’ clubs, life-skills training, and gender-sensitive school improvement planning, while the need to address cultural barriers to ensure that girls are sent to school is noted. For children with disabilities, GEQIP-E focuses on increasing the number of Inclusive Education Resource Centres (IERCs) in Ethiopia for children with disabilities (from 113 to 800) alongside other complementary activities (awareness raising, training, provision of reference materials, and creating a suitable learning environment). However, amongst both donors and government there was concern as to whether this focus was sufficient and capable of meaningfully addressing inequity in the education system. For example, both groups recognised that GEQIP-E was falling short in its ability to address multiple forms of disadvantage, such as for the poorest girls living in rural communities. For girls, a more comprehensive approach was considered to be important, for example to also address issues such as gender-based violence and menstrual hygiene. While the focus on children with disabilities in GEQIP-E was seen as representing positive progress towards inclusive and equitable education, focusing on IERCs alone was viewed as too narrow as this would only reach a small portion of children with disabilities, and some local level stakeholders viewed that current IERCs were providing inadequate support. Donors in particular stressed the need for a smarter and more integrated range of initiatives that would include other markers of difference, such as location (across and within region) and differences between high-performing and low-performing schools.

One of the key shifts of GEQIP-E is the introduction of Performance for Results (PforR) financing. This new financing approach means that the release of GEQIP-E funds depends on the achievement of a pre-defined set of results, related to the four GEQIP-E areas (efficiency, equity, quality, and system strengthening). The introduction of PforR financing is intended to strengthen the education system, which in turn is expected to improve quality and contribute to increased student learning outcomes. Individuals from both government and donor stakeholder groups believed that the PforR financing mechanism would help to address problems of previous phases of GEQIP. Some donors believed that PforR originated with them, driven by the need to demonstrate results and value for money, and so needed to convince government of the benefits:

“It took a lot of time to convince them …Partners are also not happy with this, putting money without seeing results. So, it is best convincing them in terms of, their focus should be accountable, but also pressuring them. Unless we do that, they might not be able to support.” - donor representative

At the same time, others suggested that this approach was initiated by the government (particularly MoF). While it is new for the education system, it was seen as being used successfully within a number of other sectors within Ethiopia:

“…it is not new for Ethiopia…in health system, in land management system and I think in water supply system, they have the same modality…but in education sector it is a new modality.” - federal government representative

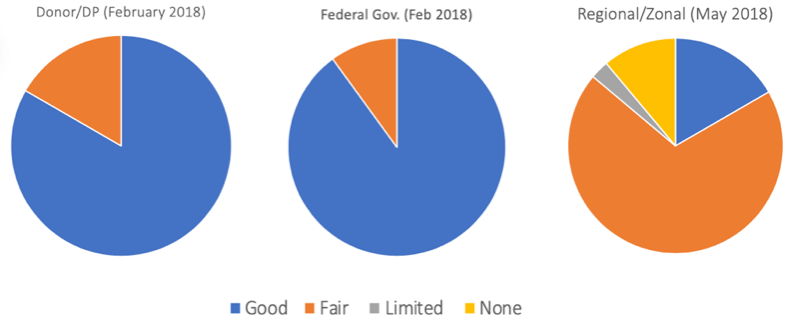

Through the interviews, a significant gap in stakeholder knowledge of the existence of the PforR financing approach of the GEQIP-E programme was identified, with stakeholders at regional level, unlikely in particular to be aware of this new approach at the time of data collection (Figure 4).3

At the federal level, stakeholders had good levels of knowledge about the PforR financing approach of the GEQIP-E. However, at the regional and zonal level, this substantially decreased with only a few stakeholders having a good understanding:

“I informally heard about it. I heard that the next GEQIP will be result-oriented. The information has not been communicated very well in the Region.” - regional government representative

“I have no clear awareness but I heard that ’P’ for ’R’ means Program for Result.” - regional government representative

At the woreda level there was a very limited understanding of the new PforR financing approach. This limited understanding was viewed by donors and federal and regional government officials as a significant challenge, especially due to the fact that the main implementation activities of GEQIP-E occurred at the woreda level:

“The other challenge may be if all parties (stakeholders) that implement the change are not aware of it, awareness creation should be done. Otherwise, the money may not be utilized based on the standards established in the shift (or new modality).” - regional government representative

The knowledge gap was viewed as being related to the way in which information on GEQIP-E was communicated, including:

While efforts had been made to disseminate information about GEQIP-E throughout the system, it was found that these efforts had not brought about the desired results. It was suggested by both donors and government stakeholders alike that urgent action was needed to address the communication gap, to help ensure the effective implementation of GEQIP-E. Suggestions for strategies to address the communication gap included the use of different types of media to communicate information, providing the information in the relevant languages where possible, and communicating with all stakeholders on a regular basis.

Concerns were raised about the type of PforR that was used and its suitability for the Ethiopian context. A number of both donor and government stakeholders viewed the type of PforR to be very rigid and have very little flexibility - either the results are achieved and funds are released or the results are not achieved and funds are not released. This was seen to be unsuitable for the Ethiopian context, given the significant diversity of the country as well as its susceptibility to shocks. This was further hampered by the lack of sufficient risk assessment carried out prior to the design of GEQIP-E. As such, some donors described the type of PforR introduced as an ‘out-dated model’:

“…as we know all the regions do not have same capacity…within the region all the woredas do not have same capacity, so ignoring the difference and expecting all the regions or woredas to achieve same performance is not fair and some of the woredas and schools may not perform up to the expectations due to the capacity problem.” - regional government representative

Further issues were identified with the Disbursement Linked Indicators (DLIs) that are being used to measure results, with some DLIs being seen as inconsistent with the overall objectives of GEQIP-E (for example, the ability of narrow indicators to achieve meaningful improvements in equity in the system). Concerns were also raised about the quality of data available which would potentially impact the ability to assess progress effectively.

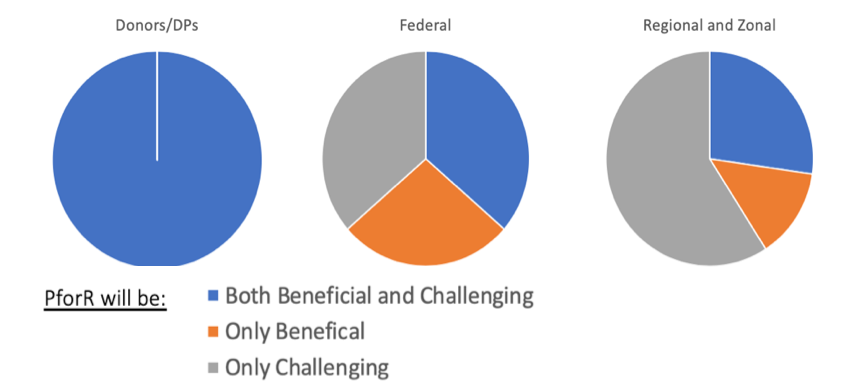

Amongst the stakeholders who were aware of the shifts to PforR financing, their expectations regarding the potential impact of this new financing modality were explored (Figure 5).

Expectations of the potential of this approach to improve the education system varied amongst different types of stakeholders, with stakeholders at the regional level of the education system less likely to be optimistic about this approach. Donors perhaps had a more realistic view of the shift to PforR financing believing that there would be both benefits and challenges in implementing this approach in the education system in Ethiopia. At the very least it was suggested that the new approach would bring about a needed shift in the attitudes of government stakeholders implementing the programme. However, concerns were also voiced by donors, with one donor suggesting that the PforR approach may undermine sustainable change within the system:

“…the whole implementation has been driven by ticking boxes and identifying targets and I don’t think it necessarily balanced that with building capacity for the longer term. I wish GEQIP II had focused a bit more on real measures of outcomes than the more input sides of things, you know.” - donor representative

Federal government officials revealed more mixed expectations regarding this approach, with some indicating that it would be only beneficial, and other seeing the new approach as only having challenges without brining benefits to the system:

“They (World Bank) feel like it was very much effective because they have tried in the health sector in Ethiopia. They said that very much effective….Personally, I believe it is very, very effective, because at least we delivered these deliverables so that to get the fund. Therefore the system will work in fact we are working more than that one even the World Bank is expecting us to work more than that one.” - federal government representative

At the regional and zonal level, government officials were most likely to view this approach as mostly challenging, although some did also suggest that they saw benefits. The different expectations of stakeholders towards PforR may have been influenced by differing levels of information amongst stakeholders about this approach, or may be due to the fact that regional and zonal government officials are more aware of implementation challenges on the ground:

“However, the challenge may be not having a common understanding. For instance, if there is difference in the feelings of donors, MOE and REBs, then this will be a challenge. So lack of common understanding will be a challenge” - regional government representative

“It may have a positive and negative impact. The positive impact will be that it encourages schools to work hard. On the contrary they may lose the budget, and without this the schools cannot operate.” - woreda government representative

An important issue that emerges from the discussions related to payment for results is whether insufficient knowledge, particularly at the local level where implementation occurs, could have consequences for meeting the DLIs. In addition, it appeared that there was a lack of clarity about the implications of not achieving the results – to the extent that this would mean the government would not receive funds for services that had already been delivered, how would shortfalls be covered? And at whose expense?

While a high level of participation amongst donors and federal government officials in the design process of GEQIP-E was found in our stakeholder interviews and dialogue workshops, one of the main criticisms of the design process has been the top down manner in which participation was elicited. In terms of the main shifts occurring in GEQIP-E, the increased focus on equity in GEQIP-E has been welcomed by both donor and government stakeholders alike, and is seen to reflect the priorities of both groups. However, questions were raised as to whether the approach is expansive enough to bring about meaningful improvements in equity. The new PforR financing approach, designed with the intention to strengthen the education system’s focus on outcomes, was received with a mixture of both optimism and scepticism amongst stakeholders, with identified barriers - including the lack of sufficient knowledge amongst those implementing GEQIP and the perceived inflexibility of the approach - requiring urgent action to ensure the success of the GEQIP-E programme.

As such, the RISE research has helped to identify potential barriers to the implementation of GEQIP-E, hopefully providing useful information for stakeholders at the early stages, which can potentially help to address these challenges and bring about greater success of GEQIP-E. The participation of key stakeholders in interviews and subsequent workshops has helped not only to validate emerging insights provided through the RISE Ethiopia research, but also to engage these stakeholders in the research process, and better ensure that the results are useful.

1 Addis Ababa, Amhara, Benishangul Gumuz, Ethio-Somali, Oromia, SNNP, and Tigray.

2 It will also be important to assess the perspectives of woreda bureau officials, as well as of school and community stakeholders. This will be undertaken in the next phase of the research.

3 During the key informant interviews participants were asked whether they had any knowledge of the new PforR financing mechanism of GEQIP-E. Responses of government officials at federal and regional/zonal level and donors were categorised as follows: ‘None’ - had not heard of PforR; ‘Limited’ – had heard of PforR but did not know what it entailed; ‘Fair’ – had heard of PforR and had some information of what it entailed; ‘Good’ – had heard of PforR and were aware of what it entailed and the potential implications for the education system.

We would like to extend our sincere thanks to all the stakeholders who shared their views with us, including government officials in the Ministry of Education and Ministry of Finance and donors including the World Bank, DFID, Embassy of Finland, JICA and UNICEF. Thank you specifically to those who provided feedback on this work including key individuals at the Ministry of Education, particularly Elias Wakjira, other government officials and donors who attended RISE Ethiopia workshops, and other members of the RISE Ethiopia team including Tassew Woldehanna (Principal Investigator), Ricardo Sabates, Padmini Iyer, Chanie Ejigu, and Shelby Carvalho, as well as members of the RISE Directorate.

Asgedom et al. 2019. Whose Influence and Whose Priorities? Insights from Government and Donor Stakeholders on the Design of the Ethiopian General Education Quality Improvement for Equity (GEQIP-E) Programme. RISE Insight Series. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-RI_2019/012.