Pauline Rose

Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre, University of Cambridge

Blog

In Ethiopia, strong political will for improving the quality of education with equity is found at the highest level of government, which in turn is reflected in the government’s education policy and plans. While this is important, a question arises as to whether it is sufficient for ensuring real progress. Ambitious intentions are translated into action only through the stakeholders working within the system, which particularly requires the involvement of those at the local level. Sufficient capacity and motivation of these stakeholders is needed to effect meaningful and sustainable change. This requires, for instance, making sure the stakeholders are consulted in the design of the reforms they will be implementing. In turn, their engagement helps to ensure that local knowledge informs the success of the design itself.

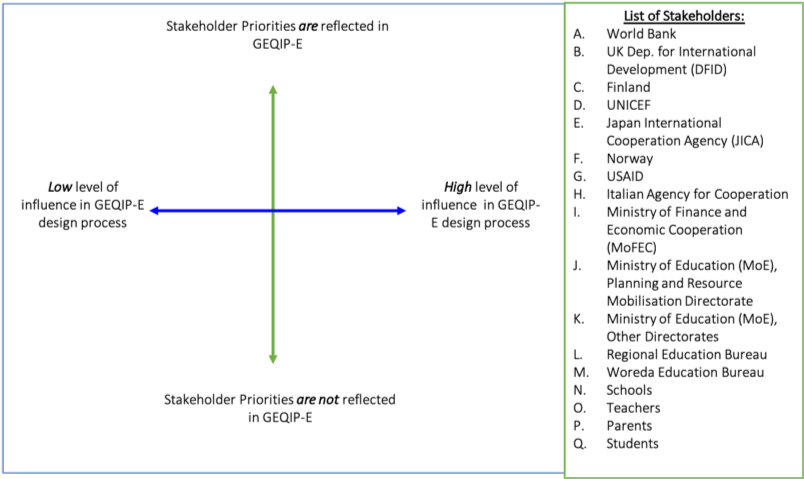

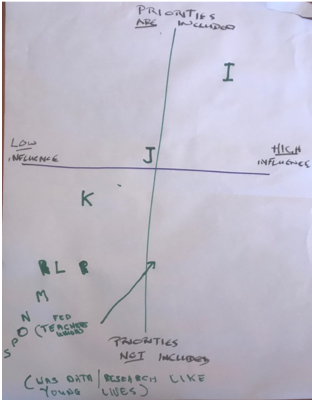

In order to explore these issues in the Ethiopian context, over the past 18 months, RISE Ethiopia has been charting the design process of the General Education Quality Improvement Programme for Equity (GEQIP-E) through the eyes of government officials from federal, regional and woreda (district) level, as well as donor stakeholders. As part of this process, the team conducted a stakeholder mapping exercise of donor and government stakeholders that explored the perceived level of influence that different stakeholders have had in the design process, and the extent to which they believe their and others priorities have been included in the design of GEQIP-E (Figure 1).

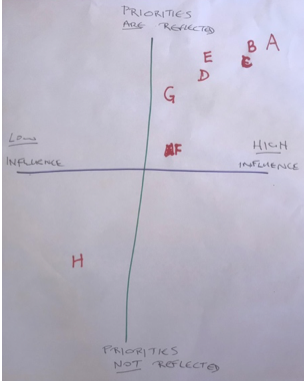

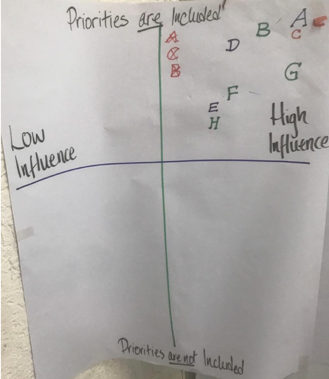

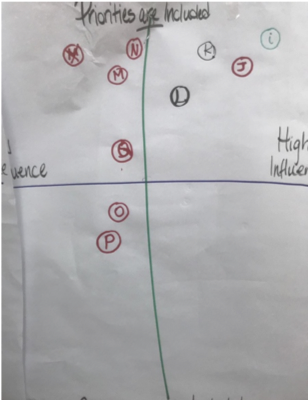

Multiple federal government and donor stakeholders noted that they had taken part in the design process of GEQIP-E, which was coordinated by the Ministry of Education (Planning and Resource Mobilisation Directorate) with close support from the World Bank. However, donors themselves viewed that the level of influence was skewed towards them. Donors viewed that the World Bank was particularly influential in the design, which was largely seen to be linked to the amount of financing that they contributed to the programme (Figures 2a-c).

|

|

|

| Figure 2a: Donor Group | Figure 2b: Government Group 1 | Figure 2c: Government Group 2 |

“The biggest influence is supposed to be the Ministry of Education. But we also know that the ones who dig deeper into their pockets sometimes have a real final say.” - donor representative

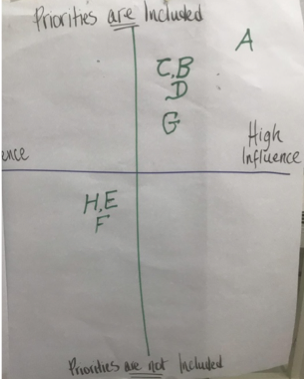

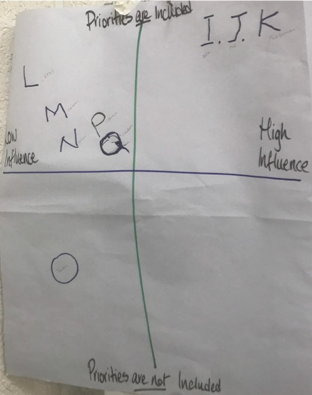

Interestingly, government stakeholders perceived that they had more influence than donors credited them with, although this varied amongst different government stakeholders. Within the government stakeholder group, it was the Ministry of Finance, rather than the Ministry of Education who were identified overall as having a higher level of influence during the design process (Figures 3a-c).

|

|

|

| Figure 3a: Donor Group | Figure 3b: Government Group 1 | Figure 3c: Government Group 2 |

One of the main criticisms of the design process—made by both donors and government stakeholders—was the top-down manner in which it occurred, with stakeholders at lower levels of the education system having significantly less participation including the woreda education office, schools, teachers, parents, and students (Figures 3a-c). While it was noted that efforts were made to consult regional and woreda level stakeholders, it was felt that this was done more on a consultative basis, rather than having a real impact on the design of the programme.

“No one has participated in the design process from this region. After [GEQIP-E] is designed we were invited to a workshop to familiarize us with GEQIP-E…but the design was already prepared by consultants . . . We gave comments on issues which are not considered in the design and which are not emphasized.” - regional government stakeholder

While the influence of the design process tipped towards donors rather than government at the federal level, the regional and woreda level stakeholders, for the most part, felt excluded from the design process.

Transforming the education system requires the participation of stakeholders at all levels of the education system. While this may not solve all problems, it may help to ensure that they are engaged in the process and help to increase the fidelity of programme implementation. Currently this has not yet been found to be sufficiently the case in Ethiopia, and raises a question as to whether the ambitious package of GEQIP-E reforms will bring about the intended results. However, as the programme is still in the early stages of implementation, a concerted effort to increase the information and knowledge of stakeholders could help to redress this shortcoming and ensure success of the GEQIP-E programme.

A more detailed report of the emerging findings of the design process of GEQIP-E is also available.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.