Michelle Kaffenberger

Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

Blog

That learning in many developing countries is in crisis has been well-established. The learning crisis was the focus of the World Bank’s World Development Report 2018, and UN global education goals highlight the need for improved learning. Yet, we are still learning much about the contours of the learning crisis, with important implications for how to address it. Recent research and analysis conducted by the RISE Programme sheds light on the severity and scale of the crisis, showing that dramatic improvements are needed to address it.

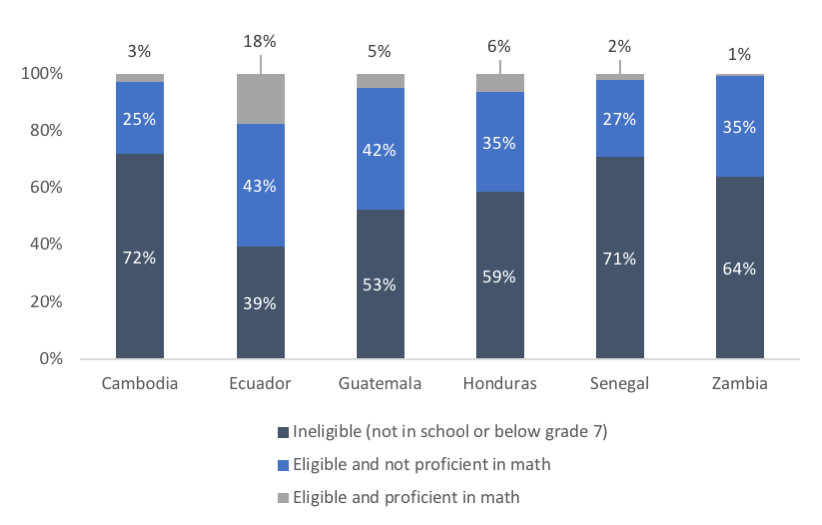

PISA for Development (PISA-D), a new effort to include more low- and middle-income countries in the internationally comparable PISA assessments, released its first results in late 2018. Test results revealed shockingly low learning levels. Across the seven countries participating, only 12 percent of children who were tested met minimum proficiency levels for math, and 23 percent for reading, compared with 77 percent and 80 percent in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, respectively. Further, the test is only administered to 15-year-olds who are in school and in at least grade seven. When children who were ineligible for the test are taken into account, only six percent of all15-year-olds on average across the PISA-D countries demonstrated proficiency in math (Figure 1). In Zambia, it was only one percent. These measures of minimal proficiency correspond with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) for literacy and numeracy, meaning these countries are far from achieving this basic goal.

The assessment includes 15-year-olds who are in school and in at least grade seven. On average only 43 percent of 15-year-olds across participating countries were eligible to participate. Source

Much focus in the global discourse is on equality of schooling and learning across groups, such as across girls and boys or the poor and the well-off, and there is indeed large variation in learning within countries. However, recent analysis shows that in many cases, achieving even perfect equality across groups would leave many without basic skills as the learning crisis affects even the more advantaged groups in low- and middle-income countries.

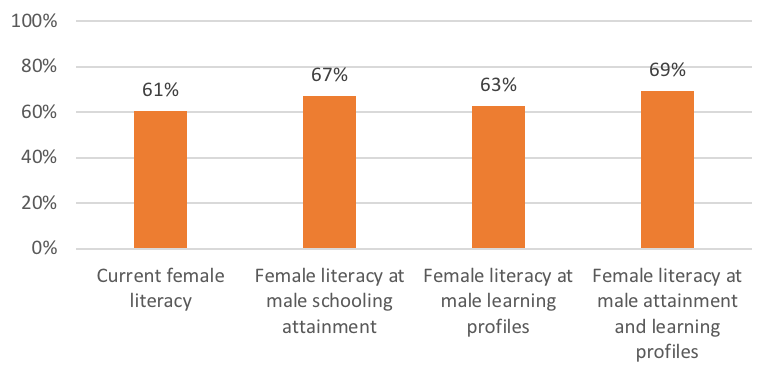

For example, analysis of nationally representative surveys from 10 countries across Africa and Asia examined equality of schooling and learning for girls with boys. It found that achieving equality in terms of years of schooling, learning per year, or both would all leave more than 30 percent of girls illiterate at completion of primary school, as literacy was low even among boys (Figure 2).

Large-scale assessments conducted by the ASER Centre in India and Pakistan and the NGO Uwezo in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda show similar results for wealth quintiles. They show that indeed learning varies by wealth, with the poor on average about 20 percentage points less likely to be numerate than the well-off. However, achieving equality in learning across wealth quintiles would still leave more than 30 percent of the poor innumerate, as even the more economically advantaged have relatively low learning outcomes. This new analysis underscores the need to improve learning outcomes, or raise the tide, for all—not just equalize currently low rates of learning across the board.

Average results across 10 countries. Source: Financial Inclusion Insights data

Finally, a new data source, the Harmonized Learning Outcomes (HLOs) developed by the World Bank, allows analysis of how learning has changed over time. The HLOs harmonize learning measures from international assessments, regional assessments, and Early Grade Reading Assessments, providing the largest set of internationally comparable learning measures available. The data show that changes in learning outcomes in recent decades have been excruciatingly slow. Across the 95 non-OECD countries with data from more than one point in time, the average score is 405 (compared to an OECD average of 500), and the median change in HLO points per year is 0.93 points. At this snail’s pace, it would take 102 years for these countries to reach the OECD average of 500. And, there is much variation within this group. Higher-performing Peru, for example, would require only 18 years to reach the OECD average, while Colombia, with an average change per year of only 0.1 point would need more than 700 years at its current trajectory to reach OECD levels (Figure 3).

Not only is progress in many countries slow, in some it is moving backwards. A recent paper on learning profiles in Indonesia found that during a period of major schooling reform, including large increases in spending, Indonesia actually saw learning decline slightly.

Small tweaks will not be sufficient to address the severity of the learning crisis, nor to increase the pace of learning enough to reach universal basic skills in the foreseeable future. The scale of the problem suggests education systems, which have successfully achieved high levels of schooling attainment in most places, now need to be reoriented to be coherent not just for schooling but also for learning. The RISE Programme is conducting research to shed light on how to accomplish this. Other efforts are working to understand how approaches that achieve learning can be dramatically scaled, such as the Center for Universal Education at Brookings’s Millions Learning Real-time Scaling Labs, Pratham and JPAL’s Teaching at the Right Level, and RTI and USAID’s Tusome Early Grade Reading Program in Kenya. New data make it abundantly clear that profound improvements are urgently needed if we are serious about achieving learning for all.

This blog was originally posted on the Brookings website on 17 May 2019 and has been cross-posted with permission.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.