Louise Yorke

University of Cambridge

Insight Note

In this Insight Note, we set out the importance of focusing on students’ socio-emotional learning, especially in the context of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. We first consider the role of socio-emotional learning in students’ education and development and also their mental health and wellbeing, and then identify specific areas that we suggest have particular importance in supporting students’ education and development during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Following the rapid expansion of education access across many Southern contexts, the importance of students’ learning outcomes has gained much attention in recent years, exemplified by the focus on the learning crisis. Yet, less attention has been paid to students’ socio-emotional learning (SEL) in research policy and practice, aimed at improving students’ education and development. This is a significant shortcoming, given the integral role that SEL is found to have on students’ outcomes in the Global North, where more research in this area has been undertaken. Such evidence identifies the important role of SEL for students’ development, both inside and outside of school. It also finds that improving students’ SEL can help to remediate for deficits in academic learning and outcomes. In addition, evidence suggests that SEL may also help to improve students’ mental health and wellbeing. More evidence is urgently needed from the Global South to better understand the role played by SEL in students’ education and development, and the factors that influence SEL in such contexts. Incorporating SEL in our understanding of students’ education and development can help to provide a more expansive and accurate definition of learning.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the essential role of SEL into focus and has drawn attention to the need to take a more holistic approach to students’ learning and development. SEL may have particular relevance in the context of the Global South, both during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic where even greater challenges have been faced in supporting students’ distance learning. Specifically, there is an urgent need to understand how students’ learning (academic and SEL) was impacted during the COVID-19 school closures, while also taking account of the impact of the school closures on students’ mental health and wellbeing. In addition, a better understanding of how SEL has helped to mitigate the impact of the school closures, and the role of students’ SEL beyond the pandemic, are important areas for further investigation.

The pressing need to bring SEL, mental health, and wellbeing to the fore in children’s learning and development in the Global South, stems from the following consequences of the global pandemic:

In summary, understanding more about the integral role of SEL provides the opportunity for a more expansive definition of learning, that has greater relevance for students’ education and development, both during, and beyond the pandemic. Enhancing the evidence-base on this broader definition of learning will further provide national and global policy actors with important information with which to develop effective strategies, particularly for those children who are most at risk of being left behind.

Socio-emotional learning (SEL) broadly refers to the acquisition of a wide range of skills and attributes, which are considered critical to students’ development, with myriad terms used interchangeably to refer to this conceptual space (Duckworth & Yaeger, 2015).1

Although precise definitions vary, SEL generally refers to a set of skills and attributes that are both different from, but also integral to, students’ academic learning.

In addition to the range of definitions and terms used to describe SEL, the frameworks for understanding and discussing SEL also vary. The Ecological Approaches to Social Emotional Learning (EASEL) Laboratory at the Harvard Graduate School of Education has created a taxonomy of outcomes, which maps skills from 40 international SEL frameworks to enable their effective comparison.2 This includes, for example, the widely used Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) framework, which describes SEL as comprising self-management, self-awareness, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making (CASEL, 2020). Another commonly recognised framework draws on the ‘Big Five’ factors of (i) task performance; (ii) emotional regulation; (iii) collaboration; (iv) engaging with others; and (v) open-mindedness (OECD, 2018). Across the different frameworks, there are both crossovers and divergences, but generally, they capture three broad areas which can be understood as: the ability to regulate and manage one’s emotions; the ability to set and achieve goals; and the ability to develop interpersonal skills that are vital for school, work, and success in life (Elias et al., 1997).

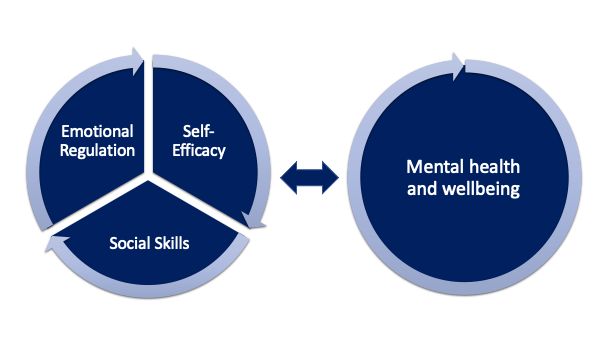

While the availability of different frameworks can provide flexibility when seeking to operationalise research in this area, it can also pose difficulties for meaningful discussions between stakeholders—including researchers, policy makers, and practitioners—and for putting the various theories into practice. Cognisant of these challenges, in this Insight Note we focus on the three broad aspects of students’ SEL, linked to the aforementioned three broad domains identified by Elias et al. (1997) as noted in Figure 1 below (i.e., emotional regulation, self-efficacy, and social skills). These broad areas are also linked to many of the existing frameworks as illustrated by the EASEL taxonomy. As we will further demonstrate, these areas are particularly important for students’ academic learning, mental health, and wellbeing in the time of COVID-19.

Socio-emotional learning is important for students’ education and development and has been shown to further influence an individual’s achievement and outcomes. This includes the level of education that students achieve, their academic progress while they are in school, their pathways beyond education including entry into the labour market, and future earnings (INEE, 2016; Brunello and Schlotter, 2010; Caspi, 1998; Dercon and Krishnan, 2009). Although researchers have avoided identifying direct causality between academic learning and SEL, it is widely accepted that SEL has a mutually reinforcing relationship with academic learning, whereby gains in one domain are said to bring about gains in the other (Brunello and Schlotter, 2010; Dercon and Krishnan, 2009; Gutman and Schoon, 2013; Heckman, 2007). From this perspective, improving students’ SEL is regarded as a potential area of intervention for improving students’ academic learning, and it may even help to remediate for deficits in academic outcomes (Borghans et al., 2008). While more evidence is needed to understand the role of students’ SEL in the Global South, suffice to say that focusing only on students’ numeracy and literacy, while no doubt important, almost certainly limits our understanding of student’s learning and development.

Box 1: Potential benefits of focusing on socio-emotional learning (SEL)

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), “mental health is a state of well-being in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community.”3 An individual’s mental health and wellbeing are believed to be determined by a range of social, psychological, and biological factors; and, as such, can be actively promoted through specific actions and interventions, including through the creation of an enabling and supportive environment both inside and outside of school. For example, the Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) has emphasised the importance of education in providing children with a stable environment in the midst of crises, and in providing a channel through which to provide support for children’s SEL, mental health, and wellbeing.4

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, evidence suggests that mental health problems affected around 20 percent of children and adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa (Atilola, 2017; Cortina et al., 2012). However, children’s mental health and wellbeing are often not given priority in the Global South in research policy and practice. Although more evidence is urgently needed, there are strong indications that improving children’s socio-emotional skills may also help to improve their mental health and wellbeing, and help to prevent adverse outcomes (Figure 2). Specifically, building social and emotional learning skills can help children respond to difficult and unexpected situations in a calm and emotionally regulated manner, enabling them to set out and develop strategies for dealing with difficult circumstances, and to interact and work with others to address problems (Arslan and Demirtas, 2016; Education Links, 2018).

Recognising the limited attention that students’ SEL, mental health, and wellbeing have received to date, in this section we identify three specific aspects of SEL—emotional regulation, self-efficacy, and social skills—together with students’ mental health and wellbeing, which we believe are of particular relevance in the time of COVID-19 (see Table 1).

| Definition | Relevance in the context of COVID-19 | |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional Regulation | Emotional regulation refers to the process by which individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express them (Gross, 1998). | May have relevance for how students cope with unexpected and difficult circumstances such as school closures, and may also impact their motivation for returning to school and learning. |

| Self-Efficacy | This refers to an individual’s belief in his or her capacity to execute behaviours necessary to produce specific performance attainments (Bandura, 1977). | May have relevance for students’ return to school and catching up on lost learning, but may also have relevance in the context of future school closures. |

| Social Skills | These are the tools we use to communicate our thoughts and feelings to others, and which guide our interaction with each other (Gresham, Sugai and Horner, 2001). | The lack of interaction caused by school closures may affect students’ social skills. Social skills may be important for eliciting support from others in times of crisis. |

| Mental Health | Mental health is a state of well-being in which an individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community (WHO, 2018) |

May be negatively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Addressing students’ mental health needs is important to enable them to engage with education and learning. |

Although we do not focus on methodological issues in this paper, it is important to note the importance of contextualising approaches to students’ SEL, mental health, and wellbeing, especially in the context of crises (e.g., INEE, 2016; Banati, Jones and Youssef, 2020; Savina and Wan, 2017; UNESCO, 2020). As such, we plan to explore the role of the family, the school environment, the community, and the wider socio-economic and political context, to help understand students’ SEL, mental health, and wellbeing. Further discussion of the challenges and approaches to measuring students’ SEL, mental health, and wellbeing in the Global South will feature in an upcoming methodological paper, including insights and lessons learned from recent research in Ethiopia.

During the COVID-19 school closures, evidence suggests that support for distance learning did not reach all students. Following the onset of the pandemic, the closure of schools was a nearly universal response across countries, affecting approximately 1.6 billion students worldwide.5 Education systems attempted to mitigate the effects of these closures through remote learning, including online teaching/lessons, educational programmes being broadcast on radio and television, and the use of take-home packages for those who do not have access to technology. However, the effectiveness of these measures has been questioned and it is estimated that around 40 percent of the poorest countries struggled to support at-risk learners during the COVID-19 crisis (UN, August 2020). Any interruption in schooling will ultimately lead to some level of learning loss and the six-month closures are estimated to have had a significant impact on students’ learning outcomes. Azevedo et al. (2020) suggest that globally, COVID-19 could result in a loss of between 0.3 and 0.9 years of school (depending on the mitigation strategies adopted), thus reducing the overall level of education that students achieve and will no doubt have serious consequences for students’ learning. Understanding the level of support that students received during the school closures and the impact of the school closures on their learning and development will be imperative.

It is likely that the school closures have impacted different students differently, with those who are most marginalised experiencing the most adverse effects. Emerging evidence suggests that the pandemic may have exacerbated existing inequalities and created new inequalities. Students who are disadvantaged—including children from poor families, girls, children with disabilities, and those living in rural and disadvantaged regions—may have faced the biggest challenges in terms of continuing their learning. In Ethiopia, emerging evidence indicates that many students, especially those living in rural remote areas where access to basic resources and infrastructure is limited, were not supported during the school closures (Kim et al., 2020; Wieser et al., 2020; Yorke et al., 2021). School principals and teachers in Ethiopia and Rwanda reported difficulties in reaching disadvantaged students (Carter et al., 2021; Yorke et al., 2021). Moreover, teachers in Ethiopia were not confident in the ability of parents and caregivers to provide support for students due to factors such as parents’ and caregivers’ high work demands and low literacy levels (Yorke et al., 2021). More generally, students whose education was interrupted at a critical stage of their learning may fare much worse, with possible impacts on their long-term learning outcomes (Azevedo et al., 2020; UN, August 2020). It will be crucial to take account of the differential impact of the school closures on students who face multiple disadvantages, while also taking account of the age and development stage of students.

Students’ mental health and wellbeing are a pressing concern, which has become even more urgent in the context of the current crisis. However, this is often missing from research, policy, and practice in the Global South. Crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, can have an adverse impact on children’s mental health and wellbeing and can provoke strong, negative emotional responses, such as panic, stress, anxiety, anger, and fear (Education Links, 2018; UNESCO, 2020). Education can be a major protective factor for children and their families in crisis and conflict situations, while the loss of education can be a significant stressor (INEE, 2016). According to the United Nations, the COVID-19 crisis is also a mental health crisis, which has both immediate and long-term impacts. In Ethiopia, it is suggested that mental health issues have increased as a result of the pandemic (UN, May 2020). Along with numerous difficulties that students may have faced due to the pandemic (e.g., food insecurity, work burden, etc.), the loss of the support received in the school environment is a compounding factor, and it is likely that their mental health and wellbeing may have been impacted (Banati, Jones and Youssef, 2020; UN, May 2020; World Bank, 2020). This in turn can have a negative impact on students’ learning and development and may limit students’ ability to focus and re-engage in learning (Immordino-Yang and Damasio, 2007; UNESCO, 2020). Understanding more about how students’ mental health and wellbeing has been affected during the pandemic—including both the risk and protective factors—is critical, and efforts must be made to prioritise students’ mental health both during and beyond the current pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the important role that schools play in supporting children’s development beyond the acquisition of academic learning. The closures of schools have helped to illustrate how many students rely on the physical setting of the school to support their essential needs, including food and nutrition, materials, and emotional and psychosocial support (ICFE, 2020; Srivastava et al., 2020; UN, Aug 2020). According to school principals and teachers in Ethiopia, some of the additional support that disadvantaged students are likely to have missed out on include school-feeding for students from low-income families,6 emotional support for girls and children with disabilities, and peer-to-peer support for low-performing students and rural students (Yorke et al., 2021). At home, especially during times of confinement or quarantine, it is likely that some children may have faced various forms of abuse and violence (ICFE, 2020). Going forward, while much of the focus has been on the loss of student’s academic learning, such as numeracy and literacy, it will be vital to consider the additional support that students have missed out on, such as social interaction and the support from teacher and peers, who in turn ensure students’ safety, health, nutrition, and wellbeing (ICFE, 2020). As schools reopen it will be critical to focus on the multiple roles that schools play in students’ development and to adopt a holistic approach to students’ learning.

As schools reopen, they are likely to face additional challenges. Considerable effort will be needed to ensure that students a) return to school, b) catch-up on lost learning, and c) adapt to new circumstances. Given the twin shocks of the school closures and the resulting economic crisis, it is estimated that dropout rates will increase as a result of the pandemic, although estimates vary by region and level of education (Akmal et al., 2020: Azevedo et al., 2020; UNESCO, 2020). In addition, students may experience reduced educational aspirations and disengagement from school, which may make it less likely for them to return and harder to catch up on the learning that they lost (UN, Aug 2020; UNESCO, 2020). Disadvantaged groups may face the biggest challenges due to the limited support they received during school closures and the likelihood that they will face additional economic pressures (UN, Aug 2020). Moving ahead, significant attention will be needed to help students catch up on lost learning and efforts will be needed to identify the individual needs of different groups of students, and to adapt responses for these groups. Considering that many countries have seen a resurgence of the COVID-19 virus, it is likely that going forward, there may be successive closures and reopenings that require shifting between in-person and remote learning, or a combination of both approaches (Dreesen et al., 2020; UNESCO, 2020; UN, Aug 2020; Srivastava et al., 2020). This will require ensuring that students themselves have important skills that can help them to benefit from distance learning and to catch-up on what they missed. For example supporting students’ self-efficacy may help to boost their belief in their ability to catch up on lost learning. In addition, it will be imperative to ensure that students receive the support that they require, especially those who were not supported during the school closures.

The COVID-19 crisis has revealed the significant shortcomings of education systems around the world and has revealed the deeply entrenched, and often hidden inequalities that different groups of students face (UN, August 2020; UNESCO, 2020). In particular, it has highlighted the range of factors that influence students’ learning and development at different levels, including with respect to individuals, the family, the school and community, and the wider context (UNICEF, 2020). More generally, the COVID-19 pandemic prompts us to assess the value and purpose of education, including what sort of skills and capabilities we are expecting education and learning to deliver (ICFE, 2020; UN, Aug 2020). Part of improving the resilience and effectiveness of education systems going forward will be ensuring that education is more flexible and can respond to, and accommodate, the needs of all students (UNICEF, 2020). There will also be a need to strengthen the education system and support students’ SEL, mental health, and wellbeing, in the effort to improve equitable and quality learning, and reduce the negative impacts of the crisis.

Akmal, M., Fry, L., Ghatak, H., Hares, S., Jha, J., Minardi, A. L. and Nyamweya, N. 2020. Who is Going Back to School? A Four-Country Rapid Survey in Ethiopia, Inidia, Nigeria and Pakistan. Available at: https://www.cgdev.org/blog/who-going-back-school-four-country-rapid-survey-ethiopia-india-nigeria-and-pakistan [Accessed: 3rd March 2021]

Arslan, S., and Demirtas, Z. 2016. Social Emotional Learning and Critical Thinking Disposition. Studia Psychologica, 58(4), 276.

Atilola, O. 2017. Child Mental-Health Policy Development in Sub-saharan Africa: Broadening the Perspectives Using Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model. Health Promotion International, 32(2), 380-391.

Azevedo, J. P., Hasan, A., Goldemberg, D., Iqbal, S. A. and Geven, K. 2020. Simulating the Potential Impacts of COVID-19 School Closures on Schooling and Learning Outcomes: A Set of Global Estimates. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 9284. Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33945 [Accessed: 3rd March 2021]

Banati, P., Jones, N. and Youssef, S. 2020. Intersecting Vulnerabilities: The Impacts of COVID-19 on the Psycho-Emotional Lives of Young People in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. The European Journal of Development Research, 32(5), 1613-1638.

Bandura, A. 1977. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191.

Borghans, L., Meijers, H. and Ter Weel, B. 2008. The Role of Noncognitive Skills in Explaining Cognitive Test Scores. Economic Inquiry, 46(1), 2-12.

Bottrell, D. and Armstrong, D. 2012. Local Resources and Distal Decisions: The Political Ecology of Resilience. The Social Ecology of Resilience (pp. 247-264). Springer, New York, NY

Bronfenbrenner, U. 1977. Toward an Experimental Ecology of Human Development. American Psychologist, 513-531.

Brunello, G. and Schlotter, M. 2010. The Effect of Non-cognitive Skills and Personality Traits on Labour Market Outcomes. Analytical report for the European Commission prepared by the European Expert Network on Economics of Education.

Carter, E., Leonard, P., Nzaramba, S. and Rose, P. 2021. Effects of School Closures on Secondary School Teachers and School Leaders in Rwanda: Results from a Phone Survey. Available at: https://www.educ.cam.ac.uk/centres/real/publications/School%20closures_brief.pdf [Accessed 1st March 2021]

CASEL. 2020. Leveraging the Power of Social and Emotional Learning. Available at: https://casel.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CASEL_Leveraging-SEL-as-You-Prepare-to-Reopen-and-Renew.pdf [Accessed 29th January 2021].

Caspi, A. 1998. Personality Development Across the Life Course. In W. Damon & N. Eisenberg (Eds.). Handbook of Child Psychology: Social, Emotional, and Personality Development (pp. 311–388). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Cortina, M. A., Sodha, A., Fazel, M. and Ramchandani, P. G. 2012. Prevalence of Child Mental Health Problems in Sub-saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166(3), 276-281.

Dercon, S. and Krishnan, P. 2009. Poverty and the Psychosocial Competencies of Children: Evidence from the Young Lives Sample in Four Developing Countries. Children, Youth and Environments 19(2): 138-163.

Dreesen, T., Akseer, S., Brossard, M., Dewan, P., Giraldo, J.P., Kamei, A., Mizunoya, S. and Correa, J.S.O. 2020. Promising Practices for Equitable Remote Learning Emerging Lessons from COVID-19 Education Responses in 127 Countries. Innocenti Research Briefs. Available at: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/1090-promising-practices-for-equitable-remote-learning-emerging-lessons-from-covid.html [Accessed 18th January 2021].

Elias, M.J., Zins, J.E., Weissberg, R.P., Frey, K.S., Greenberg, M.T., Haynes, N.M., Kessler, R., Schwab-Stone, M.E. and Shriver, T.P. 1997. Promoting Social and Emotional Learning: Guidelines for Educators. ASCD.

Duckworth, A. L. and Yeager, D. S. 2015. Measurement Matters: Assessing Personal Qualities Other Than Cognitive Ability for Educational Purposes. Educational Researcher, 44(4), 237-251.

Education Links. 2018. Social and Emotional Learning in Crisis and Conflict Settings. Available at: https://www.edu-links.org/learning/social-and-emotional-learning-crisis-and-conflict-settings [Accessed 29th January 2021].

Gresham, F. M., Sugai, G. and Horner, R. H. 2001. Interpreting Outcomes of Social Skills Training for Students with High-Incidence Disabilities. Exceptional Children, 67(3), 331-344.

Gross, J. J. 1998. The Emerging Field of Emotion Regulation: An Integrative Review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271-299

Gutman, L. M. and Schoon, I. 2013. The Impact of Non-cognitive Skills on Outcomes for Young People. Education Endowment Foundation, 59(22.2), 2019.

Heckman, J.J. 2007. The Economics, Technology, and Neuroscience of Human Capability Formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(33), 13250-13255.

Immordino-Yang, M.H. and Damasio, A. 2007. We Feel, Therefore We Learn: The Relevance of Affective and Social Neuroscience to Education. Mind, Brain, and Education, 1(1), 3-10.

International Network for Education in Emergencies [INEE], (2016). Psychosocial Support and Social and Emotional Learning for Children and Youth in Emergency Settings. INEE Education Policy Working Group (EPWG) and INEE Standards and Practice Working Group (SPWG). New York, NY: Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE). Available at: https://inee.org/system/files/resources/INEE_PSS-SEL_Background_Paper_ENG_v5.3.pdf [Accessed: 3rd March 2020].

International Commission on the Futures of Education [ICFE]. 2020. Education in a Post-COVID World: Nine Ideas for Public Action. Paris, UNESCO. Available at: https://en.unesco.org/news/education-post-covid-world-nine-ideas-public-action [Accessed 29th January 2021]

Kim, J., Araya, M., Ejigu, C., Hagos, B., Rose, P. and Woldehanna, T. 2020. The Implications of COVID-19 on Early Learning Continuity in Ethiopia: Perspectives of Parents and Caregivers. Research and Policy Paper No. 20/11. REAL Centre, University of Cambridge.

Organisation for Econoimc Co-Operation and Development [OECD]. 2018. Social and Emotional Skills for Student Success and Well-Being: Conceptual Framework for the OECD Study on Social and Emotional Skills. OECD Education Working Paper No. 173. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=EDU/WKP(2018)9&docLanguage=En [Accesssed: 3rd March 2021].

Savina, E., and Wan, K. P. 2017. Cultural Pathways to Socio-Emotional Development and Learning. Journal of Relationships Research, 8.

Srivastava, P. Cardini, A. Matovich, I., Moussy, H., Gagnon, A. A., Jenkins, R., Reuge, N., Moriarty, K. and Anderson, S. 2020. Policy Brief: COVID-19 and the Global Education Emergency: Planning Systems for Recovery and Resilience Task Force 11 COVID-19: Multidisciplinary Approaches to Complex Problems. Available at: https://inee.org/system/files/resources/T20_TF11_PB6.pdf [Accessed 18th January 2021].

United Nations [UN]. 2020. Policy Brief: COVID-19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health. Available at: https://unsdg.un.org/download/2158/32179 [Accessed 3 March 2021]

United Nations [UN]. 2020. Policy Brief: Education During COVID-19 and Beyond. Available at: https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-education-during-covid-19-and-beyond [Accessed 29th January 2021]

UNESCO. 2020. How Many Students Are at Risk of Not Returning to School? UNESCO COVID-19 Education Response. UNESCO. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373992 [Accessed 18th January 2021].

UNICEF. 2020. Building Resilient Education Systems beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic: Considerations for Education Decision-Makers at National, Local and School Levels. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/romania/reports/building-resilient-education-systems-beyond-covid-19-pandemic [Accessed: 3rd March 2021].

Wieser, C., Ambel, A. A., Bundervoet, T. and Haile, A. 2020. Monitoring COVID-19 Impacts on Households in Ethiopia. Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33824 [Accessed 1 March 2021]

World Bank. (2020). The COVID-19 Pandemic: Shocks to Education and Policy Responses. The World Bank, Washington D.C. Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33696 [Accessed 18th January 2021].

World Health Organisation [WHO]. 2018. Mental Health: Strengthening Our Response. World Health Organisation. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response [Access 3rd March 2021].

Yorke, L., Rose, P., Woldehanna, T. and Hagos, B. 2021, in press. Primary School-Level Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Ethiopia: Evidence from Phone Surveys of School Principals and Teachers. Perspectives in Education.

This research is funded by the Lego Foundation and Research for Improving Systems of Education (RISE) programme. We would like to thank members of the RISE Ethiopia team at Addis Ababa University for feedback into the design of this work, including Professor Tassew Woldehanna, Dr Belay Hagos, Professor Amare Asegdom, Professor Tirussew Tefera, and Professor Girma Lemma. Particular thanks to Chanie Ejigu for co-ordinating the research. We are also grateful to Professor Sileshi Zeleke and Professor Belay Kibret for their input. We are very grateful to Amy Jo Dowd, Eve Hadshar, and Celia Hsiao from the Lego Foundation for their helpful input into this paper, as well as members of the RISE Directorate for their feedback.

Yorke, L., Rose, P., Bayley, S., Wole, D. and Ramchandani, P. 2021. The Importance of Students’ Socio-Emotional Learning, Mental Health and Wellbeing in the time of COVID-19. 2021/025. https://doi. org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-RI_2021/025