Jacobus Cilliers

Georgetown University

Blog

Two field experiments in South Africa demonstrate that improving teaching of mother tongue literacy boosted both mother tongue and English reading skills, while improving teaching of English literacy negatively impacted mother tongue literacy for struggling students.

This blog was originally published on the Center for Global Development website on 20 June 2023.

The theoretical and empirical case for mother tongue instruction is compelling. The theory of cognitive development suggests that children learn better when they can associate new concepts with familiar words and phrases from their home language. Empirically, numerous studies have shown that children who start learning in their mother tongue tend to perform better academically. They demonstrate a deeper understanding of the subject matter and develop superior comprehension skills compared to their peers who start their education in a second language. Furthermore, learning in a familiar language can help students build confidence and self-esteem, leading to a more positive educational experience overall.

However, despite the solid rationale for mother tongue instruction, policymakers in developing countries face a challenging task of reconciling this with the strong demand from parents for their children to be educated in international languages such as English or French. This desire often stems from a belief that proficiency in these languages will lead to better job opportunities and economic prospects in the future. This trend has led to a significant shift in language policy over the past few years, with more countries moving towards an international language as the medium of instruction. The economic implications of language proficiency, therefore, play a crucial role in shaping educational policies.

The majority of evidence supporting bilingual education and mother-tongue instruction comes from developed nations in the global north. However, the situation in developing countries, and African countries, in particular, presents a unique set of challenges due to their high degree of linguistic diversity and larger linguistic differences between the mother tongue and the second language. In these settings, the transition from learning in a mother tongue to a second language that is linguistically very different can be daunting for students. Evidence on when it is most efficient to make this transition is often theoretical with limited empirical data.

A unique pair of field experiments allows us to examine the reciprocal causal relationship between literacy in a mother tongue (L1) and a second language (L2). We evaluated two very similar structured pedagogy programs aimed at improving teaching of early grade literacy in poor public schools in South Africa, called the Early Grade Reading Studies (EGRS). The programs were implemented by the same organization, and were very similar in design and quality of implementation. A key difference is that one program (EGRS I) focused on the teaching of the home language, and the other (EGRS II) centered on English as a second language. We assessed and tracked a group of incoming primary school students over a period of four years, and also surveyed teachers and observed their teaching in the classrooms.

We find the following:

First, both programs were well-implemented, and succeeded in meeting their primary objectives of improving teaching practices and student literacy. For example, almost all teachers in both programs reported to have received the additional materials provided by the program, and participated in the training at the start of the program. There were also similarly-sized effects on teaching practices. For example, the probability that a child received individual attention from a teacher increased by between 33 and 40 percent in the two studies. The program that targeted L1 instruction improved L1 literacy1 —by 0.25 standard deviations (SDs) after two years—and the program that targeted L2 instruction improved L2 vocabulary by 0.34 SDs and decoding skills by 0.13 SDs, after three years.

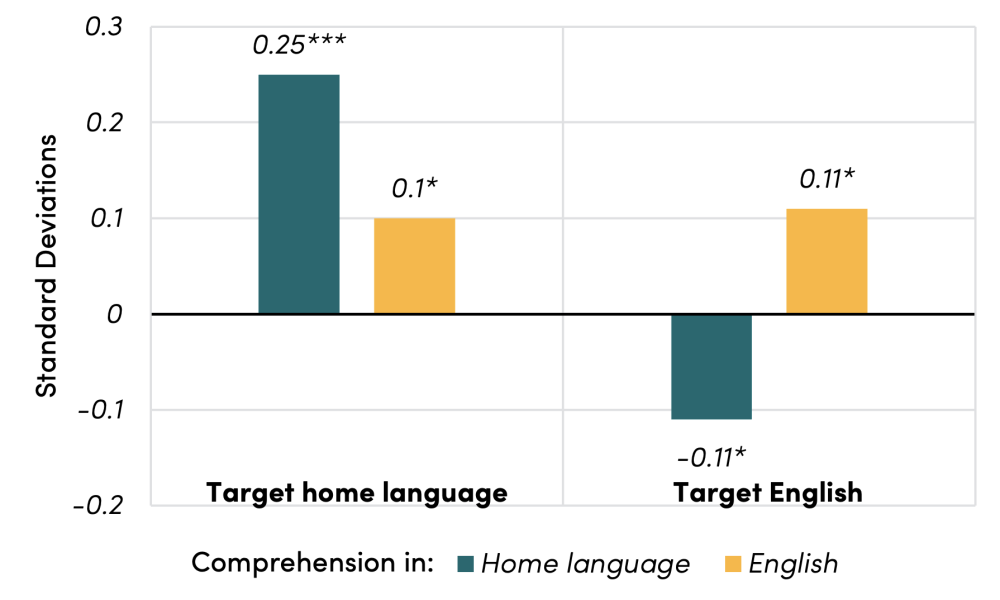

Second, targeting home language instruction improved students’ English Oral Reading Fluency (ORF) and reading comprehension, by 9 and 15 percent (or 0.09 and 0.1 SDs), respectively (See Figure 1). Moreover, targeting L1 instruction had similarly-sized impact on L2 reading comprehension and caused larger gains in L2 ORF, compared to targeting L2.

Notes. Each bar indicates the magnitude of the treatment effect in terms standard deviations. The left two bars indicate the impact of EGRS I, which targeted teaching of home language literacy; right two bars show the impact of EGRS II, which targeted teaching of English literacy. The color of the bars denotes the dependent variable: home language (green) and English (yellow) reading comprehension.

Third, targeting English instruction reduced L1 ORF and comprehension, by 11 and 7 percent (or 0.15 and 0.11 SDs). These negative effects were concentrated in students at the bottom of the performance distribution. Interestingly, the program caused a positive transfer in L1 letter recognition, but only for students in the top half of the distribution.

These results are consistent with the simple view of reading (SVR), which argues that reading comprehension requires both strong decoding skills and oral vocabulary skills. A weakness in either will lead to weakness in reading for meaning. For EGRS I the improved decoding skills in L1 were probably transferred to the L2. Most learners had sufficiently high levels of vocabulary in L1 and thus improved their word decoding skills in their L1 when teachers were supported by a structured pedagogical program. But for EGRS II students were learning a new language at the same time as learning to read. Consequently, there was less of an improvement in decoding skills, and since L1 decoding skills were also weak, there was limited improvements in reading fluency.

The negative impact of EGRS II on L1 literacy for the weaker-performing students is a bit of a puzzle. It might be due to the large linguistic distance between indigenous South African languages and English. Teachers might have applied the same sequencing of decoding skills—i.e., the same sounding out syllables and letter blends—that they received for L2 to their L1 classes. But this is the wrong starting point, given the different orthographic rules in the different languages. This could have confused students who are already struggling with basic decoding skills. It might also be due to the fact that the program improved curriculum adoption, but the curriculum was too ambitious for the weaker students, and they learnt less as a result. We can only speculate on this interpretation, and more research is required to fully understand the result.

Taken together, these results suggest that decoding skills are best taught in the L1, since children already possess sufficient oral language comprehension. Moreover, decoding skills are more easily transferable across languages with similar orthographies, whereas oral language skills, such as vocabulary, do not transfer in the same way. Furthermore, teaching of decoding skills in L2 may worsen students’ decoding skills in L1, especially if there is a large orthographic distance between languages and students have not sufficiently mastered L1 decoding skills.

These results have important policy implications for multilingual settings where children do not enter school with sufficient prior exposure to the L2. First, students should be taught in their home language, especially in the early grades. Second, programs aimed at improving early grade reading should not prioritize L2 literacy instruction.

One caveat is that our results are drawn from two experiments in two different populations. Even though the interventions themselves were equivalent, the different populations might have had different responses to the treatment. The populations are very similar in terms of socio-economic status and education outcomes, but a key difference is the students’ home language. Theoretically, the extent of language transferences from L2 to L1 might depend on the degree of similarity between the two languages. These are only conjectures, of course, and future studies comparing L1 and L2 interventions within the same language or the same language group would provide further insights.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.