Lant Pritchett

Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

Blog

As usual Ludger Woessmann and Eric Hanushek (this time with Annika Bergbauer) have written an interesting, provocative, and relevant paper—this time on testing. If you haven’t read Eric on teachers and his classic JEL review paper; Ludger on declining productivity in the OECD or on class size (an appreciation of this paper would have saved a decade of debate on external validity); or their joint work (with others) on autonomy, education systems, and learning outcomes; or on economic growth and learning (here and here), well, you should (have already).

Their new paper “Testing” uses PISA data over time to investigate what types of assessment systems affect learning. That is, they don’t ask, “Does assessment improve performance?”, which is too broad a question to be amenable to a sensible answer, but are able to compare external versus internal assessments and ones that make school comparisons and ones that do not.

Since this blog post is really just a loss-leader to get you to read the paper, I just want to make two points.

First, the question of “testing” in education often begins with a heated debate (or lack thereof, just strong positions) about the experience with the American approach to assessment and accountability under the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) of 2001. While that debate is fascinating and informative, it is not at all obvious that it is relevant to India or Nigeria or Indonesia.

One can easily imagine reasons why the impact of introducing standardized testing with external comparisons across schools would be wildly different in India and the United States. In the United States, one might imagine schools are somewhere near an efficiency frontier and hence any reform that placed more emphasis on accountability of schools for results on standardized tests might necessarily imply less time and attention to other elements of schooling that parents and educators find equally important. Any debate about NCLB in the United States therefore has to ask not just whether assessment of the NCLB type actually improves performance on the skill sets it measures, but also whether this is a priority and what is sacrificed in achieving those gains.

But on outcomes, efficiency, and accountability one can easily see that the United States and India are at very different places. On the MCAS (Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System), sixth graders have to read and respond to paragraphs—long passages with sentences like: “The flying frog is a fascinating example of an animal that has taken its family traits to extremes in adapting to its special environment.” In a national survey of adult women in India, only 35 percent of those who had completed grade 6 could read a single simple sentence like: “Farming is hard work.” The ASER survey suggests that in rural India less than half of those in grade 5 can read a simple grade two story of a few simple sentences. Two India states participated in PISA (like) assessments, Himachal Pradesh (HP) and Tamil Nadu. In HP, only 2.1 percent of students were above level 2 in reading proficiency versus 58.1 percent in the USA and in the USA only .6 percent were “below level 1b” (essentially so low they could not be reliably tested)—in HP this was 22.5 percent of students aged 15.

Direct measures of teacher attendance and activity find that in unannounced visits in rural India, about 23.6 percent of teachers are absent during school time—and even more were not in class or engaged in any instructional activity. A household survey in India in 2005 found that in government schools more children were “beaten or pinched” by the teacher (29 percent) than were praised (25 percent).

On measures of the efficiency of public school spending in India, on average, about 2.5 times more is spent per pupil than private schools and yet, on average, produce much lower levels of learning. Even correcting for student selection using an experiment, the estimates in one Indian state (Andhra Pradesh) are that the private sector produces the same learning outcomes (actually the same in many subjects and better in one) at a third of the per pupil cost of government schools. In contrast, in the United States the debate about efficiency gains from private (or charter) schools is so heated in part because all agree the differences are modest—no one suggests that in the United States the private schools are factor multiples more cost efficient at producing measured learning as they appear to be in India.

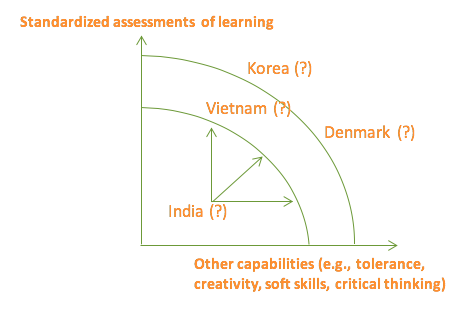

Figure 1 places countries in their (roughly) known position of outcomes on standardized assessments of reading and mathematics across countries on the vertical axis and at hypothesized, conjectured, positions on “other elements” of education on the horizontal axis (the figure has question marks because there are no widely accepted measures of these other elements). For instance, we know that on standardized estimates of mathematics like PISA, South Korea’s average is much higher than Denmark’s (in 2012, 554 versus 500). But perhaps these high achievements of Korean students are the result of very high stakes in the student examination system that causes enormous effort and focus on the kinds of skills and capabilities the PISA mathematics assesses. In Denmark, there is consensus that they trade-off higher mathematics performance for other valued outputs of education and hence there is no appetite for a reallocation along an efficiency frontier towards higher scores in mathematics. Vietnam’s participation in PISA surprised nearly everyone when their results were near (or above) those of OECD countries, hence achieving learning results far above the level “expected” for their income per capita. Vietnam’s 2009 PISA reading score was 487, the USA was 500, and Himachal Pradesh’s 2009 PISA-plus score was 319—over 150 points behind Vietnam. Do Denmark and Vietnam have roughly similar scores and perhaps Denmark is producing lots of other outputs or perhaps it isn’t (no one can say for sure)? It is hard to believe that India isn’t just wildly inside its possibility frontier in producing all outcomes of schooling.

Figure 1. At an efficiency frontier the choices are about trade-offs of outputs; when countries are inefficient there is the possibility of (much) more of all outputs

All of this is just to set up what I believe is one of the most important findings and figures in Woessmann et al.’s “Testing” working paper: the interactionmakes a big difference to the results. Figure 2 (Figure 3 in the paper’s numbering) shows the interaction of the estimated impact of introducing testing of various types, which distinguishes between standardized external comparisons, standardized monitoring, internal testing, and internal teaching monitoring.

Figure 2. Effect of student assessments on math performance by initial achievement levels

For countries that begin very far behind, at a PISA score of 350, the estimated impacts of introducing either standardized external comparisons or standardized monitoring are huge—a country “effect size” on the order of 1 or larger (as the typical country student standard deviation in PISA is around 70 to 80). Whereas for countries that start with OECD level performance (the PISA, as an instrument of the OECD, was normed to a mean of 500 for the OECD and OECD student standard deviation of 100) the impact of the other types of testing is much smaller (though still statistically significant for three of the types of testing).

All of this emphasizes the importance of a system approach to education and to evidence about what to do to improve education. If high-performing systems are high performing precisely because they have created mechanisms that create accountability for education results—including learning—then one would rightly expect introducing new modes of accountability would have relatively small impacts. In contrast, if low-performing systems are low performing precisely because they have not developed modes of accountability that are coherent for learning and which result in massive inefficiencies (as seems plausible), then introducing new modes of accountability via testing and assessments (of the right type, shared in the right way) could potentially have massive impact.

On a methodological note, this also suggests that although using cross-national evidence makes it much harder to produce clean and convincing causal identification, extrapolating results from one context to another may have even bigger problems by ignoring systematic differences (see Pritchett and Sandefur 2015 showing an instance with higher mean square error of prediction of impact from using “rigorous” but non-contextual estimates over contextual estimates, even if not well-identified). Even if perfectly rigorous, unassailable evidence from multiple studies in multiple states suggested that NCLB had small, zero, or even negative impacts in the United States, this would, with the existing cross-national evidence (and the obvious cross national differences in measures of system outcomes, efficiency, and accountability) be completely and totally irrelevantfor assessing the likely impacts of introducing standardized external comparisons or standardized monitoring in a low-performing country like India (or many others). Rigorous evidence isn’t when it is extrapolated outside the conditions in which it was generated.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.