Michelle Kaffenberger

Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

Blog

A new source of global learning data shines a timely light on the size and dynamics of the learning crisis.

“Are children really learning?” A new source of foundational learning data gives a fresh perspective on this question. The answer (and the data) are explored in a new UNICEF report, which finds that, tragically, children are not learning nearly enough. We contributed to the report, using the new data to analyse learning trajectories and potential learning loss resulting from Covid-induced school closures. Here we highlight our five main takeaways from the report on the depth of the learning crisis and how to tackle it.

The report draws on the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) from 32 low- and middle-income countries. MICS began assessing children’s reading and numeracy in the surveys’ most recent/6th round of data collection (dubbed MICS6). The surveys are household-based, which means the assessments include both in- and out-of-school children and youth.

The assessments are calibrated to measure progress on SDG 4.1, assessing reading and numeracy skills that the SDGs—and many national curricula—expect children to master by Grade 2. Figure 1 shows the percentage of Grade 3 students in each country who have actually mastered these skills:

In the median country, only 30 percent of children have reached early grade reading targets, and only 18 percent have mastered basic math. This reaffirms data from elsewhere showing that children often do not gain even foundational skills in the early primary school grades. Low learning in early grades suggests a need for education systems, including politicians, policymakers, administrators, teachers, families, and donors alike, to prioritise foundational learning.

The report analyses learning trajectories which visualise learning as children progress from one grade to the next (Figure 2). The learning trajectories from the MICS6 data show slow progress. At the current rate of learning per year, it would take a child in the average county more than seven years to learn the skills they are expected to master by Grade 2.

This echoes other policy simulations (by Kaffenberger and Pritchett and Pritchett and Sandefur) showing that more years of schooling alone will be insufficient to address the learning crisis—learning per year is just too shallow. Instead, children must learn more in each year they spend in school. This is especially critical in the early grades since this is when the data show children start to fall behind. As the report says: “Greater investment is needed, therefore, to steepen the learning trajectories so that children enter Grade 3 knowing how to read and handle basic numeracy, thereby enabling them to fully engage in increasingly complex curriculum as they advance through school.”

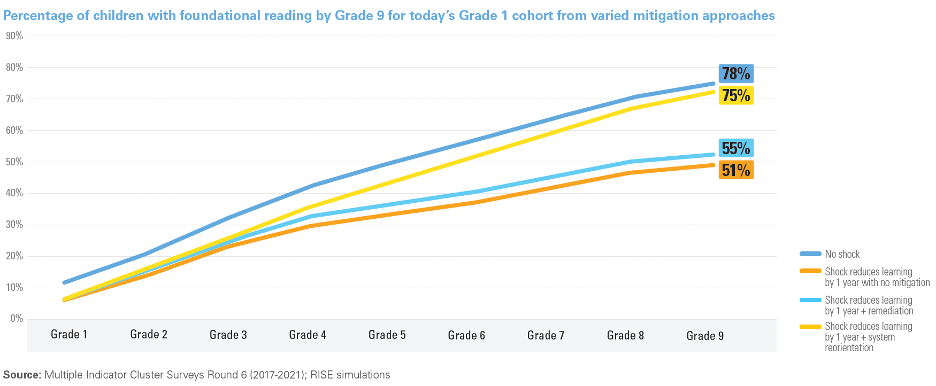

The need to think about learning as a cumulative process is driven home by the simulations of COVID-19 related learning loss. These simulations, applying a methodology from earlier RISE work, show how small initial losses caused by school closures—which thus far have ranged from a few weeks to two full school years—can continue to grow even after children return to school. The intuition is that as children fall further and further behind the level assumed by the curriculum, they have an increasingly difficult time benefitting from instruction.

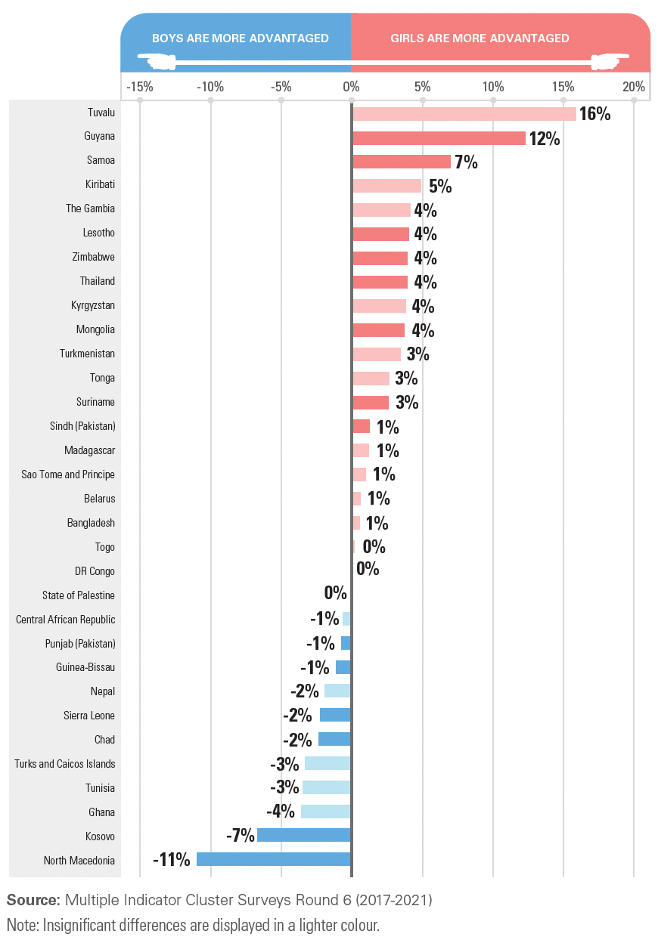

The report also does a thorough analysis of differences in learning between groups within countries, such as comparisons between the rich and poor and girls and boys. For us, the most striking results are the relatively small gaps between demographic groups. When 70 percent of all children cannot read by Grade 3, it puts in perspective the fact that children from the richest quintile are 16 percentage points more likely to be able to read than their peers in the poorest quintile (p.21). In a similar vein, the results for gender show that “in most countries there is not a notable difference in learning outcomes by gender” (p.28).1

Next to the modest differences in learning within countries, the differences in learning between countries are huge. For example, Bangladesh and Ghana have similar GDP per capita, and Ghana has historically spent more on education. However, nearly five times as many children in Bangladesh learn to read and twice as many gain numeracy by Grade 3 than in Ghana (Figure 1). This does not mean that Ghana should simply do what Bangladesh does, but it does show that very different outcomes are often possible even at similar levels of development.

Make no MICS-take, the 6th MICS survey round is a much-needed boost to globally scarce data on learning. MICS6:

Like any dataset, it also has certain limitations in keeping with how it was designed. For example, its test for foundational skills is relatively stringent (to pass the reading test, students had to correctly read aloud 90 percent of the words in an approximately 70-word story, and then correctly answer all five comprehension questions). It was also designed to be a binary measure—pass/fail —rather than allowing for more fine-grained analysis of different student learning levels. However, we have already found the dataset to yield rich insights (which we set out in a working paper and Insight Note), and we hope it will receive increasing scholarly and policy attention in the years to come.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.