Michelle Kaffenberger

Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

Blog

A new working paper from the RISE Indonesia Country Research Team has the incredible benefit of having panel data on learning—tracking the same children on what they know over time—a rarity in the development space. By assessing children over time, we can see the gains and also whether or not skills are retained.

Members of the RISE Indonesia team take up skill acquisition and retention with the Indonesia Family Life Surveys data, looking at skills on some simple arithmetic questions. They use data on children in 2007 and 2014 which includes questions ranging from quite simple (e.g., 49 - 23) to slightly more difficult (e.g., reducing 56/84 and 1/3 -1/6), to more difficult (0.76 - 0.4 - 0.23 and 5% interest on Rp75,000). All of these represent skills that should be gained during a student’s primary education—and hopefully retained into adulthood. The authors use Item Response Theory to generate a score for numeracy skills for each child in each testing year that is the mean probability that the child answered any given question correctly.

They analyze two groups: those who were 7 to 9 years old in 2007 (and hence 14 to 16 years old in 2014), and those who are 10 to 12 years old in 2007 (and hence 17 to 19 years old in 2014). What they find is astounding. Over the seven years most of these children see almost no gain in their ability to complete math problems. Those who are 7 to 9 years old in 2007 on average had about a 30 percent probability of answering a question correctly in 2007. By 2014 that probability had increased by only a few percentage points—despite seven years of potential learning.

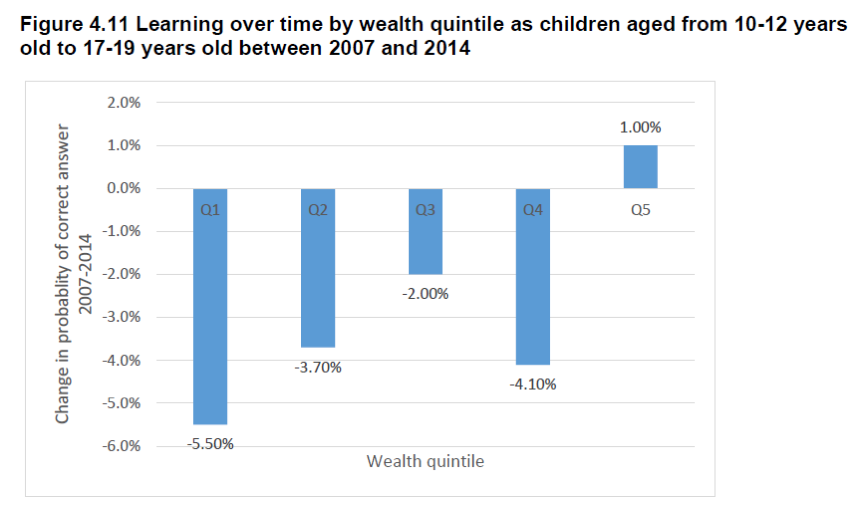

The findings for those aged 10 to 12 in 2007 are even more drastic—their likelihood of answering a math question correctly declined by 2014. They were actually less likely to answer correctly than seven years earlier. To dig deeper, the authors divide this cohort into their household’s wealth quintiles, using an asset index. They find (Figure 4.11) that numeracy scores declined for all but the wealthiest income group. Among the poorest quintile in this cohort, the likelihood that children could answer a question correctly declined by 5.5 percentage points—from a low base of less than 30 percent to begin with. And, because these are the average changes across lots of children, this means some children surely gained skills over those seven years, while some children’s ability declined even more than the graph indicates.

These findings have multiple implications:

As international goals shift to addressing the learning crisis, we may need to address a learning retention crisis as well.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.