Michelle Kaffenberger

Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

Blog

Guaranteeing quality education for every girl requires a two-pronged approach: bailing out the boat and fixing the hole in its hull. We need to invest in today’s primary school girls—who are future adolescents—to ensure that they gain the foundational skills they need to start and stay on a strong learning trajectory. Programmes aimed at girls who have already reached adolescence need to focus on closing learning gaps, not just inducing greater attendance, so that girls reap the full benefit of additional time spent in school.

You only have to look at modern-day heroines Malala Yousafzai and Greta Thunberg to appreciate the power that adolescent girls have to change the world. Their potential is limitless. But tragically, too many adolescent girls struggle to reach their full potential, often because education systems are failing them. Many stakeholders blame early marriage, pregnancy, or entry into the workforce for pulling girls out of school, and propose solutions to tackle these. But these pulls are often symptoms of dropout. The deeper cause is often low learning pushing girls out.

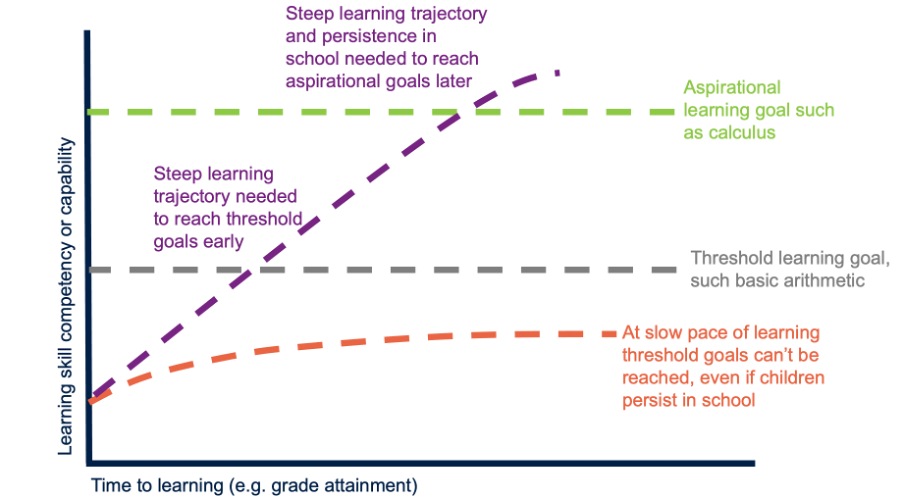

A new RISE Insight Note discusses how insights from learning trajectories (analysis of how much children learn over time) can inform approaches to supporting today’s and tomorrow’s girls. For many children in developing countries, learning trajectories are too shallow and flatten out far too quickly. The illustration in Figure 1 shows how damaging flat learning trajectories can be. The purple line shows a learning trajectory that makes enough progress to reach threshold goals, like basic arithmetic, early and sets girls up to reach aspirational goals (like advanced calculus) by the end of school. But the orange learning trajectory is too flat, meaning that children learn little and fall behind the level of instruction. Even if a girl whose learning follows this trajectory persists all the way to the end of school, she can’t reach even the threshold goal at this slow learning pace.

Source: Adapted from Belafi, Hwa, and Kaffenberger, 2020.

Evidence suggests that these flat learning trajectories themselves are a cause of dropout. Girls—and boys—often drop out of school because they realise they are learning too little for education to provide a secure future. They report low learning driving them to seek other ways to provide for themselves, such as through marriage or employment. In other words, girls who are learning little make (often rational) choices to find alternative routes to stability.

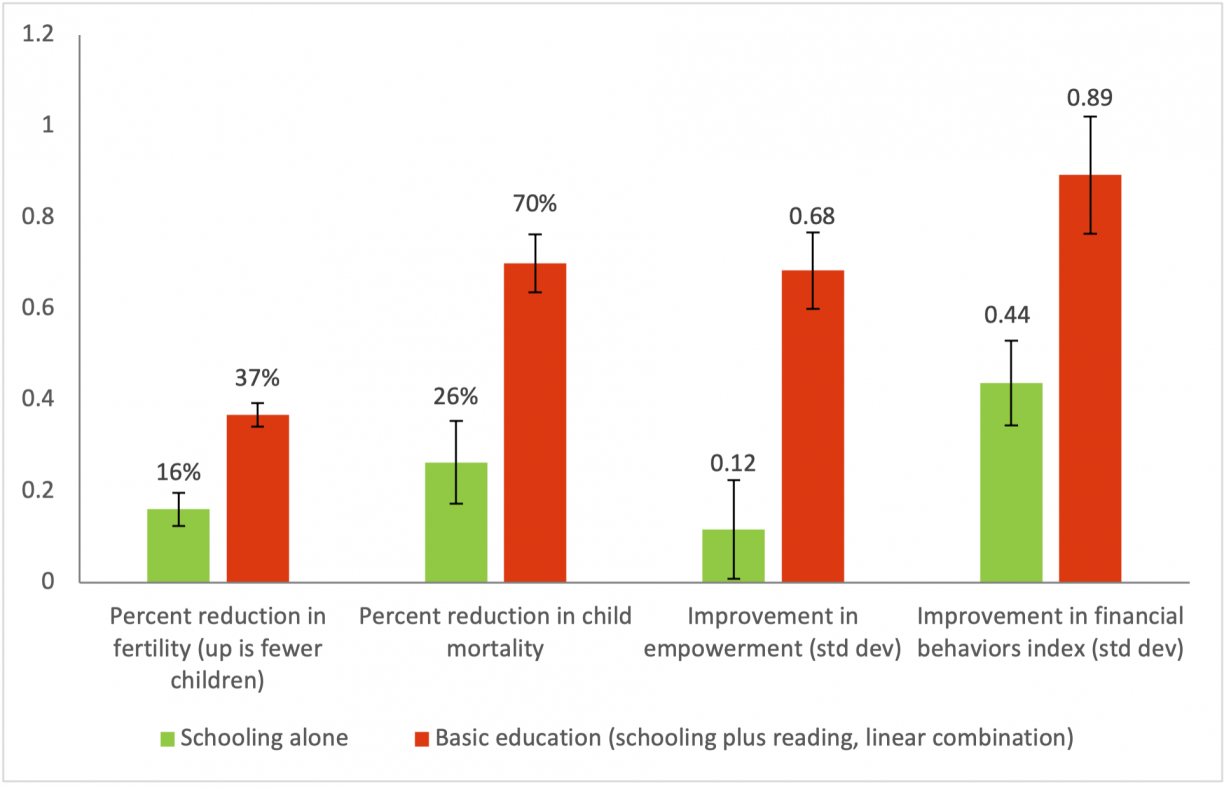

While an extensive literature documents the benefits of girls’ schooling for their later life outcomes, more recent work shows the gains are much larger when girls learn while they are in school. One recent RISE paper estimates that achieving literacy, just one aspect of learning, accounts for one-third to one-half of the benefit of education to some later life outcomes. Moreover, if, as the evidence discussed above suggests, girls are making a rational decision to drop out based on their own perceived progress in school, then it is the education system that has failed, not the girl. Forcing or inducing girls to stay in school without offering them support to make the best use of their time there is unfair and unproductive. Programmes should aim at preparing adolescent girls to be as successful as possible in life, not simply at keeping them in school longer.

Source: Kaffenberger & Pritchett, 2021.

Today’s 5- or 10-year-old will be the adolescent of the future. If we want to improve the learning of adolescent girls over the coming 10-20 years, the most effective way to do this will be to ensure that the young children who are in primary school now receive a quality education. This is ‘fixing the hole in the boat’. We have much more knowledge now than we did 10 or even 5 years ago about how to get young children learning both at a classroom level and at the whole system level, and we owe it to these adolescents-of-the-future to translate this knowledge into better teaching for all.

The cumulative impacts of getting a 5-year-old on a steep learning trajectory are impressive. When children master foundational skills early in life, they are on a course for better learning outcomes. Conversely, children who don’t master the basics often struggle to catch up.

Guaranteeing the future of tomorrow’s adolescent girls need not come at the expense of today’s adolescent girls, but we must be clear-eyed about the best way to support them. Programmes to help girls who have already reached adolescence should focus on not only supporting them to stay in school, but also ensuring that they are learning while they are there. This means aligning curriculum and instruction to their learning needs and offering them support to catch up.

The challenges facing today’s and tomorrow’s adolescent girls are significant, but so is these girls’ potential. A strategy aimed at giving every girl the best shot possible at a productive and fulfilled life must be anchored around the learning of both young and adolescent girls. A two-pronged approach—one that invests in tomorrow’s adolescents by ensuring universal mastery of foundational skills and supports today’s adolescents by meeting them where they are on their learning trajectories—can help every girl reach her full potential.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.