Pauline Rose

Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre, University of Cambridge

Blog

Last week, I was privileged to join a gathering of around 800 experts and advocates in London at the Global Disability Summit. The Summit has marked a step change in the commitment to promoting the importance of better data and evidence to inform policy and practice. This commitment is clearly articulated in the Summit’s Charter for Change. It is further elaborated in the Statement for Action to Accelerate Equitable and Quality Inclusive Education for Children and Youth with Disabilities, signed by over 30 global organisations. The Statement promotes the generation and use of “robust data and evidence for inclusive planning, programming and for ensuring accountability” in the effort to achieve transformational education for children with disabilities. At the Summit, a number of governments and international organisations committed to collecting disability-disaggregated data in their surveys.

It is vital that these commitments are acted upon through continued momentum beyond the Summit. There is a growing evidence base that can be built on: research funded through the ESRC-DFID Raising Learning Outcomes programme provides a snapshot of key messages that can inform policy. As part of this, our work in the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre uses the questions developed by the Washington Group on Disability Statistics to identify whether children with disabilities in rural Punjab, Pakistan are in school and learning.

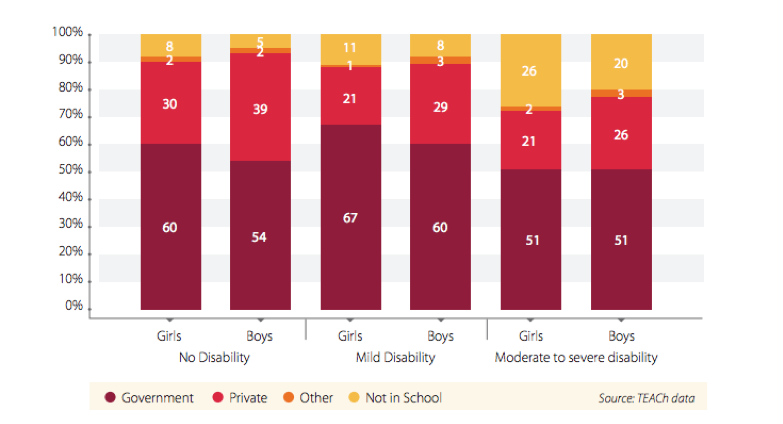

The results are perhaps surprising: many more children with moderate to severe disabilities are in mainstream schools than we anticipated. Moreover, a sizeable proportion are in private schools, suggesting their parents are willing to invest in the education of their children with disabilities where they can: poverty is a greater constraint to attending a private school than disability (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Type of school attended by disability and gender

As in many other contexts, overall learning levels in rural Punjab are low. Importantly though, those with disabilities who make it to school are learning at similar (if slightly lower) levels than their peers. The biggest difference in learning for those with and without disabilities comes when access and learning are looked at together. This suggests that schooling does make a difference, although more can be done (and needs to be done) to ensure schools and teachers have the support needed to promote an inclusive learning environment.

As part of the RISE Programme, we will shortly be starting our fieldwork in Ethiopia to identify the influence of the government’s third national General Education Quality Improvement Package, referred to as GEQIP-E as it now has an explicit focus on equity and supporting children with Special Education Needs. To date, reliable data on the education of children with disabilities in Ethiopia is lacking. Drawing on experience from our work in Pakistan, we will be using the Washington Group questions to identify children with disabilities and find out whether they are in school. For those in school, we will assess their learning to gauge whether they have the same chance to learn as their peers—and, ultimately, the effect that the GEQIP-E programme is having.

We hope that the evidence generated will provide a strong basis for informing strategies to accelerate equitable and quality inclusive education for children and youth with disabilities in Ethiopia and beyond, as promoted in the Statement for Action at the Global Disability Summit.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.