Jonathan London

Leiden University

Insight Note

- Many features of Vietnam’s education system and its performance around learning can be traced to specific features of the country's political settlement and an extraordinary and sustained societal commitment to promoting education

- Public spending on education exceeds 5.5 percent of Vietnam's rapidly expanding GDP, outpacing other countries in the region and in the same income group

- Despite international test results, the general consensus in Vietnam is that the education system is underperforming and the knowledge, learning, and skills that Vietnamese children need (and want) remains lacking

- Although many efforts have been made to reduce inequality in the school system, there is an increasing sense that it is not what you know, but who you know and whether individuals can afford the informal costs associated with quality education in Vietnam

- Vietnam displays high levels of public engagement around education, with extensive coverage and debate on education policy

- Vietnam’s education system, like education systems in all countries, is deeply embedded in its social context

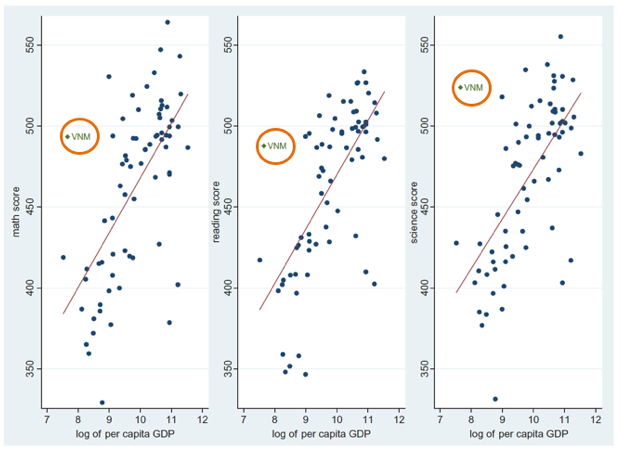

Vietnam’s record of expanding access to education, and especially its performance on international assessments such as PISA, has raised questions about what Vietnam got right, how, and why and what insights Vietnam’s experiences might offer for efforts at improving the performance of education systems around learning worldwide.

However impressive, Vietnam’s achievements in education are in key respects unsurprising. This is a country that reflects an extraordinary societal commitment to education forged through centuries of anti-imperial and anti-colonial struggle and decades of efforts to promote access to education to all citizens. To this day, education policy in Vietnam is conducted with patriotic zeal. The veneration of learning in Vietnamese culture has been widely noted, as has Vietnamese families’ willingness to invest time and resources into their children’s learning.

But that is not all. The Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) continues to place education at the center of its political agenda and has redistributed resources to poorer regions more than states in most other developing countries. This has permitted rapid expansion in enrollment and in average years of schooling nationwide and a narrowing of gaps in enrollment across regions and urban and rural zones. Gaps in enrollment between boys and girls in secondary education have been eliminated. Further, though ruled within a Leninist framework, Vietnam displays high levels of public engagement around education, reflected in the extensive coverage education receives in state-run media and in the more spirited debates that animate discussions of education policy across a range of social media platforms.

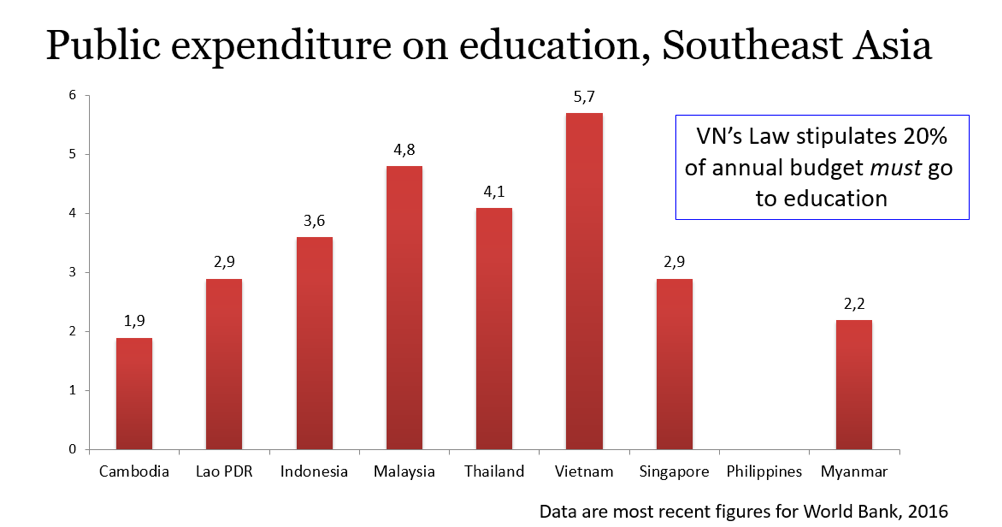

Nor did Vietnam’s “all in for education” spirit cease with the country’s transition to a market economy. On the contrary, Vietnam’s growing economy promises returns to education and the expectation of expanded economic opportunity and has thus incentivised household investments in education. Public spending in education exceeds 5.5 percent of a rapidly expanding GDP, outpacing other countries in the region and in Vietnam’s same income group. Taken together, these factors provide an understanding of the sources of Vietnam’s impressive achievements.

As difficult as it is for international observers to grasp, the sentiment within Vietnam—among Party leaders, policymakers, and more resoundingly still among the general population—is that Vietnam’s education system is underperforming.

While Vietnam’s education system has performed admirably with respect to expanding enrollments, increasing average years of schooling, and generating eye-popping test results, its effectiveness in promoting the types of knowledge, learning, and skills that Vietnamese children need and want remains lacking. This is a point on which virtually all Vietnamese agree.

While the CPV has worked consistently and commendably to promote more equitable access to quality education, progress on this front has slowed amid intensifying inequalities and an increasing sense and reality that in the contemporary Vietnamese labour market what matters most is not what you know or how well you learn, but rather who you know or how much you are willing to pay to for grades, a diploma, extra-tutoring, opportunities to re-sit exams, the chance to sit in a “high quality” classroom within a public school, and other institutionalised and pervasive informal costs attached to education in Vietnam. Such trends call into question the principle of quality education for all and effectively undermines the values of social solidarity and equity to which the CPV has long pledged its allegiance.

More recently, rapid expansion in foreign investment-driven, low-skilled, labor-intensive manufacturing and services has been associated with declining enrollment in upper-secondary education and declining returns to education in some provinces.

Additional problems concern the uneven quality of education across regions and, as will be observed below, a decentralised system of state finance that at times supports and at other times appears to undermine the achievement of laudable national development goals around equity and quality education for all.

Despite Vietnam’s education system’s many effective aspects and its famous PISA results notwithstanding, it is the questions about the system’s underperformance with respect to learning, skills acquisition, equity, and quality (and what to do about it) that are of greatest interest to the Vietnamese. Indeed, education in Vietnam is a “lightning rod” issue, especially given Vietnam’s high levels of public and household education spending, the tremendous energy and expense Vietnamese children and their families devote to learning, and Vietnam’s apparently lackluster performance in moving into higher-productivity sectors upon which the country’s development depends.

For all of these reasons, Vietnam itself stands to benefit from an improved understanding of its education system—what works, what doesn’t, and why—and what is to be or can be done. And other countries can learn, too.

Recent literature on the political economy of education and learning raises fundamental questions about the performance of Vietnam’s education system and what features of Vietnam’s politics, public governance, and attributes of its education system can help to explain the country’s mixed education performance.

In a series of RISE working papers, RISE team members have developed a well-elaborated framework for the analysis of education systems’ coherence for learning. Outside of RISE, Brian Levy’s landmark study of basic education in South Africa and Sam Hickey and Naomi Hossain’s edited volume on the politics of education in developing countries develop analytic frameworks that both complement and stand in productive tension with research being undertaken in RISE.

The RISE Programme’s Vietnam Country Research Team (CRT) has taken up these frameworks and the questions they pose, viewing them as a basis for an iterative process of research and policy dialogue around what works and what doesn’t work in Vietnam’s education system, and why and what Vietnam and the world can learn from this as a guide for action.

Over the last three years, the RISE Vietnam CRT has undertaken a series of investigations on the development and attributes of Vietnam’s education system and its performance, from Party headquarters and the Ministry of Education in Hanoi to schools and classrooms across the country. While the research is ongoing, we observe three features of the politics of education in Vietnam that are particularly striking and worthy of consideration in broader discussions of research on improving systems of education globally and in Vietnam itself: political commitment, public governance, and societal buy-in.

Many features of Vietnam’s education system and its performance around learning can be traced to specific features of Vietnam’s single-party political settlement and, in particular, the CPV’s extraordinary and sustained commitment to promoting education. While the character and motivations of CPV’s commitment to education are complex and the efficiency and effectiveness of its education policies are the subject of research and lively debate, the resources and energy the party devotes to education have been substantial.

It is certain that part of Vietnam’s leadership commitment to education has to do with the education system’s socialisation functions. In Vietnam, as in other single-party states, the socialisation functions of the education system are especially pronounced, exemplified by the red scarf millions of Vietnamese students don on a daily basis and the ubiquitous daily recitation of patriotic memes. Still, while CPV’s interest in the socialising functions of education may help to explain its political commitment to education, it is less helpful in explaining the apparent effectiveness of Vietnam’s education system in promoting learning.

Indeed, while some features of socialisation may benefit learning, others may not. Many Vietnamese, for example, have complained that their education system’s orientation toward the absorption of information through memorisation (or ‘rote learning’) promotes test-taking skills more than learning, while others have questioned the relevance of curricula. In Vietnamese policy circles, debate frequently dances around, but rarely addresses, tensions and contradictions stemming from the need to promote critical thinking, intellectual curiosity, and skills for a world market within an education system geared to promote normative conformity.

Despite these concerns, there are many other features of Vietnam’s political settlement and political system that support the education system’s coherence for learning. Among these is undoubtedly Vietnam’s distinctively Leninist framework, in which the organisation and operation of official government structures and service delivery units is interpenetrated by structures and organs of the communist party.

The suggestion here is that having both official government structures and a perpetual organised parallel political process within them makes "management" relationships within the bureaucracy more accountable to national political priorities than might be the case in a purely top-down government bureaucracy (even in a democratic polity), where local officials, managers, and service-delivery might not “give a hoot” about education or learning and may face no countervailing political force.

While this is conjecture, it is intriguing when we compare features of public governance and education in Vietnam with other countries. For example, one of the noted features of Vietnam’s education system is the professionalism of its education workforce. Teachers show up on time and are driven by a professional ethos, in part because Vietnam’s political organisation demands consistent attention to education from the level of policymaking to the daily management of Vietnam’s 63 provinces, 700+ districts, 11,000+ communes, and urban wards, and to its tens of thousands of schools. The same cannot be said for most countries.

An additional indication of political commitment and a likely contributor to Vietnam’s record of performance has been that, while private spending on education continues to grow, the Communist Party of Vietnam has itself maintained high levels of public support for education, approaching 5.7 percent (in 2017) of an expanding GDP, compared with 3.6 for Indonesia (2015) and 2.6 for the Philippines (in 2012). Annually, education spending accounts (by formal requirement) for 20 percent of the state budget. The question of how much public and private value Vietnam gets for spending and efforts leads us to a second aspect of the politics of learning: public governance.

In the policy literature, public governance comprises features of social relations and formal and informal institutions that shape conduct and outcomes of public policy and, in the context of education, the development, daily operations, and performance of education systems. A key insight from recent literature is that features of public governance across, and even within, countries can powerfully shape the coherence or incoherence of education systems for learning.

In its ongoing analysis of Vietnam’s education system, the RISE CRT has observed two features of public governance of special interest for their potential importance in promoting or limiting future improvements in the system’s coherence for learning. The first of these has to do with specific features of decentralisation. Foreigners unfamiliar with Vietnam may be surprised to know the country and its education system are governed through a highly and possibly over-decentralised system within which Vietnam’s 63 provinces are given unusually high levels of discretion with respect to the allocation of budgetary funds for education.

An additional surprise is that, while in formal terms Vietnam’s education policies require the collection of comprehensive data on education, including teacher, students, and school performance, the reality is that the collection and (especially use) of information is extremely thin, excepting all but a small minority of provinces.

The situation is in some respects paradoxical. On the one hand, central norms dictate provinces must allocate 20 percent of their annual budgets for education, which seems indicative of Vietnam’s commitment to education. On the other hand, however, Vietnam’s law on the national budget makes zero specification of norms and standards provinces may not violate. Further, data from interviews with dozens of central level officials indicates that, to date, only in a small minority (less than a third) of provinces are there meaningful interactions among these different stakeholders. The result, effectively, is 63 provinces with 63 education systems with little or no national overview of how provinces are managing education or performing with respect to the promotion of learning.

The third and perhaps most troublingly fuzzy but undeniably real feature of the politics of learning in Vietnam concerns what, for lack of a better way, can be summarised as Vietnam’s societal commitment to education. Though Vietnam exhibits a one-party system that limits space for political pluralism, the country exhibits high levels of civic engagement in education. Though their channels of expression may be limited to online expression, individual complaints and appeals mechanisms, and state-owned media, it is nonetheless the case that Vietnam exhibits dense civil society-like properties in the field of education.

Part of Vietnam’s societal buy-in is quite literal. In the late 1980s, Vietnam experienced an acute fiscal crisis that effectively required the abandonment of central planning in favour of a market-based economy. The education system was hit hard, with many localities experiencing 30 and even 40 percent declines in enrollment over a two-year period, delays in staff pay lasting months, the works. To prevent the collapse of the public education system, Vietnam’s government and people resorted to a system of formal and informal co-payments to finance education; an arrangement that persists until this day. Since then, there has been explosive growth in enrollments and average years of schooling and broad improvements in test scores. Moreover, Vietnam has performed well in redistributing financial resources in a way that permitted other areas of the country to catch up.

While these arrangements should not be romanticised (for example, they have at times created space for opaque and corrupt management practices), the fact that up to 40 percent of finance for public education is out of pocket has undoubtedly invited elevated levels of public engagement in the education system. Somewhat paradoxically, controversies and scandal regarding perceived corruption or the questionable value of extensive informal payments, have kept the citizenry engaged.

All of this complexity points to a fundamental reality: Vietnam’s education system, like education systems in all countries, are deeply embedded in their social context. While recent scholarship on the politics of education has highlighted features of political settlements and public governance, the analysis of education systems must feature a sociologically thick analysis of education systems that standard econometric approaches cannot provide. Vietnam suggests we stand to benefit from a still more encompassing analysis of how education systems and learning (or not learning) are embedded within specific social and institutional contexts. As such, efforts to understand the politics of education stand to gain from a rigorous engagement with the vast literature on the sociology of education, which recent literature on the politics of education has largely ignored.

Among middle- and lower-income countries and indeed among all countries, Vietnam is a country that reflects the sort of “all for learning” spirit that is all too often lacking. In its efforts to further promote learning, the country has many things in its favour, including an enduring political and societal commitment born of historical experiences specific to it and an expanding and globalising economy that presents good opportunities and incentives.

Vietnam’s education system is well organised and effective in many respects and messy and ineffective in others, while public and private spending on education is on the rise. Evidence suggests spending per se will not buy improvements in education systems performance. The challenge is both to "spend the money and to use it well." Overall, the good news is that Vietnam does well and can still do better. Our hope is that the RISE research can generate ideas and evidence that can help point ways forward.

London, J. 2019. Vietnam: Exploring the Deep Determinants of Learning. RISE Insight. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-RI_2019/011.