C. Obinna Ogwuike

Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa (CSEA)

Insight Note

Education remains crucial for socioeconomic development and is linked to improved quality of life. In Nigeria, basic education has remained poor and is characterised by unhealthy attributes, including low quality infrastructure and a lack of effective management of primary and secondary schools. Access to education is a massive issue—according to the United Nations, there are currently about 10.5 million out of school children in Nigeria, and 1 in every 5 of the world’s out-of-school-children lives in Nigeria despite the fact that primary education in Nigeria is free.

A considerable divide exists between the northern and southern regions of Nigeria, with the southern region performing better across most education metrics. That said, many children in southern Nigeria also do not go to school. In Nigeria’s South West Zone, 2016 data from the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Education reveals that Lagos State has the highest number of out of school children with more than 560,000 children aged 6-11 not going to school. In the South South Zone, Rivers State has the highest number of out-of-school children; more than 900,000 children aged 6-11 are not able to access education in this state. In Enugu State in the South East Zone, there are more than 340,000 children who do not have access to schooling (2016 is the most recent year high-quality data is available—these numbers have likely increased due to the impacts of COVID-19).

As part of its political economy research project, the RISE Nigeria team conducted surveys of education stakeholders in Enugu State including teachers, parents, school administrators, youth leaders, religious leaders, and others in December 2020. The team also visited 10 schools in Nkanu West Local Government Area (LGA), Nsukka LGA, and Udi LGA to speak to administrators and teachers, and assess conditions. It then held three RISE Education Summits, in which RISE team members facilitated dialogues between stakeholders and political leaders about improving education policies and outcomes in Enugu. These types of interactions are rare in Nigeria and have the potential to impact the education sector by increasing local demand for quality education and government accountability in providing it. Inputs from the surveys in the LGAs determined the education sector issues included in the agenda for the meeting, which political leaders were able to see in advance. The Summits culminated with the presentation of a social contract, which the team hopes will aid stakeholders in the education sector in monitoring the government’s progress on education priorities.

This article draws on stakeholder surveys and conversations, insights from the Education Summits, school visits, and secondary data to provide an overview of educational challenges in Enugu State with a focus on basic education. It then seeks to highlight potential solutions to these problems based on local stakeholders’ insights from the surveys and the outcomes of the Education Summits.

Basic education in Enugu state includes pre-primary, primary, and junior secondary education. A key objective is to deliver comprehensive, compulsory, and quality education to all children of school age. The Universal Basic Education (UBE) programme, which took effect across Nigeria in 2004, aims to provide free and compulsory education for all children aged 6-15. While the programme is widely believed to have contributed to the improvement of school enrolment and completion rates nationally, evidence on the extent of its impact is mixed.

Over the past few decades, basic education in Nigeria’s South East Zone has improved considerably compared to other states in Nigeria’s southern zones. Its number of out-of-school children and the number of children enrolled in school are the lowest and highest, respectively, in the country. However, hundreds of thousands of children in the South East Zone still do not go to school. The Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC) reported in its 2018 “Compendium of Public and Private Schools Basic Education Profile & Indicators in Nigeria” that Enugu State has a 50.38 percent primary completion rate, which drops to 30.71 percent for junior secondary schools.

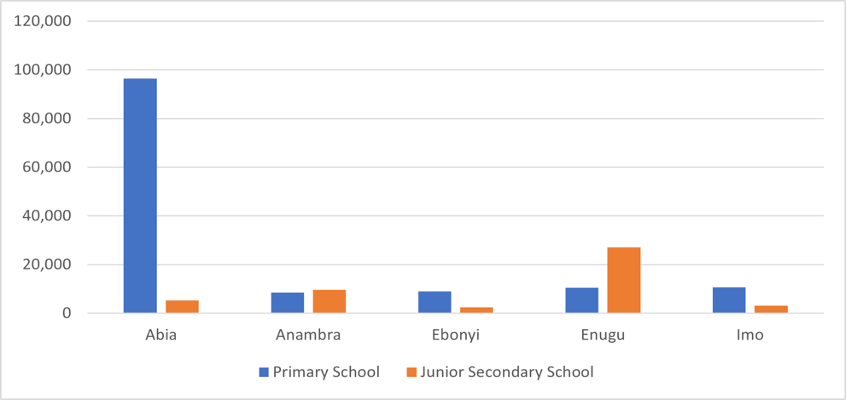

The available data suggests that recent gains have not eliminated the problems of education in the state. For instance, the most recent comprehensive data collected by the Nigerian government and the UK-funded Education Sector Support Programme from 2012-2016 shows mostly positive trends, but also shows certain negative trends. To take one example, the number of classrooms needing repairs rose by 30.6 percentage points from 35.9 percent in 2011 to 66.5 percent in 2013. Enrolment rates also declined from 239,235 in 2011/2012 to 177,375 in 2013/2014. In 2016, the number of primary school teachers in Enugu stood at 10,415, which was significantly lower than the 27,026 junior secondary school teachers in the state (Figure 1). This imbalance is striking when contrasted with other South East Zone states such as Abia, where the number of primary school teachers far exceeds the number of junior secondary school educators.

Source: Open Africa

Enugu State’s education sector challenges include a lack of governmental supervision or management; the absence and/or ineffectiveness of education committees; misalignment between curriculums and the job market; poor teacher remuneration and working standards; unsafe learning environments; and inadequate or non-existent hygiene, water, and sanitation facilities. We present the challenges below with additional input gleaned from our RISE stakeholder surveys.

Nigerian education-related projects suffer severely from poor supervision by the government. Existing systems do not allow for transparency and accountability in the way funds are allocated. Awarded projects often follow a politicised pattern, and little is done about maintenance of pre-existing projects. As a result, the learning environment is characterised by dilapidated infrastructure. The RISE survey found widespread perceptions that infrastructural shortcomings are a determining factor in poor access to education in Enugu State. For instance, when asked to choose one reason for poor access to education in their LGA, 26 percent of those interviewed in Enugu’s Nkanu West LGA pointed to shortages of school infrastructure and teachers. In Udi LGA, this figure was 25 percent and in Nsukka, 27 percent. RISE survey respondents also expressed some concern about governance quality in the education system. Approximately 12 percent of the 199 respondents in Nkanu West LGA believed that poor governance of the education sector was the primary reason for poor education in that LGA. In Nsukka and Udi LGAs, this number was around 13 percent.

Education committees are largely absent or ineffective at ensuring a more stable and dynamic education system in Enugu State. Moreover, few initiatives seek to incorporate and maintain existing governing bodies like School Based Management Committees (SBMC). A committee encompassing local education stakeholders (such as parents, teachers, and religious and traditional rulers), educators, and education state actors should play an integral part in any basic education system, as envisioned by the National Council of Education’s school-based management initiative launched in 2005.

Surprisingly, primary data gathered by the RISE Nigeria team revealed that relatively few education stakeholders see SBMCs as an urgent priority. For example, only 9 percent of respondents described education committees as an urgent priority for improving education in Nkanu West LGA, while 6 percent and 10 percent saw education committees as an urgent priority in Nsukka and Udi LGAs, respectively.

Enugu State’s basic education curriculum lacks a balance between theoretical and practical knowledge and fails to prepare students for modern employment. There is a huge gap between the relevance of subjects taught and the basic demands of the job market. When asked to choose one problem with the local education sector, 16 percent of respondents in Nsukka LGA stated that teaching does not adequately target the job market. This number was higher in Nkanu West LGA at 21 percent and lower in Udi LGA at 13 percent.

Anecdotal evidence shows that graduates are increasingly unlikely to pursue teaching as a profession in government-owned schools. A widely highlighted cause is the lack of adequate, regularly provided welfare and remuneration packages for staff. This view is supported by RISE field research, which found that financial insecurity has been a major setback for education development in Enugu state. Ten percent of those interviewed in Nkanu West LGA stated that

financial insecurity is the primary issue in the education sector in the LGA, while 15 percent and 17 percent respectively in Udi and Nsukka LGAs identified financial insecurity as the main problem in their LGA’s education sectors. Currently, primary school teachers are paid below the government-approved minimum wage. Retired teachers rarely receive earned pensions when due. Educators argue that government allocations favour secondary school teachers more than primary school teachers. This favouritism is more evident in urban areas relative to rural areas. Teachers consequently seek deployment to urban areas, which drives teacher shortages in rural areas.

In addition to this persistent deficiency of government funding for teachers, little or no periodic incentives are made available for efficient teachers or well performing school-age children. A combination of poor welfare packages and unpromising incentives stresses teachers’ commitment to delivering quality education.

Insecurity and criminal activities have degraded the quality of education at all levels in Enugu State due to the rise in cultism. Cultism refers to a problem experienced in Nigerian schools and college campuses in which secretive groups conduct illicit or destructive activities such as violence or drug use. Previous literature on cultism in the Nigerian education system suggests it is a result of a complex web of causes including deficiencies in basic infrastructure, parents’ inability to inculcate basic cultural values into children, and peer pressure.

However, one key driver of the poor security standards in basic education is surprisingly simple—a lack of proper gate-fenced walls around school buildings. Of the 30 schools surveyed in three LGAs in Enugu state, only 6 schools have gates/external walls. This defect gives rise to wide-ranging negative outcomes from abuse of students to trespassing in schools and community learning environments. Some fence-less schools are reported to be used as a base for criminal activities, a loitering place for the homeless or displaced persons, or as a den of cultists. While learning activities occur in the daytime, illicit activities take place in the buildings at night. In the absence of proper fencing, there has also been an increase in land disputes between schools and churches, which can negatively impact schools’ ability to provide adequate infrastructure to students.

Poor hygiene conditions are predominant across public schools in Enugu State, which generally lack access to clean water and adequate toilet facilities. Subpar sanitary conditions and contaminated drinking water contribute significantly to mortality and morbidity among children due to an increase in vulnerability to water borne diseases. Children’s ability to learn is also negatively impacted by water, sanitation, and hygiene conditions.

This problem is corroborated by RISE field surveys in Enugu. Only 8 percent of respondents in Nkanu West stated that inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) facilities were the primary contributor to poor education outcomes in the state. However, this number was much higher in Udi and Nsukka LGAs, where 23 percent and 25 percent of respondents, respectively, believed that poor WASH conditions were the main factor hampering education delivery. Learning outcomes are further reduced since school-aged children return to their homes to access clean drinking water during school hours. Logically, the more this occurs, the more enrolment, retention, and completion rates are reduced.

At the RISE Summit held in Enugu State in December 2020, stakeholders expressed the importance of comprehensive supervision and adequate funding of education. Attendees proposed the establishment of task forces in the LGAs to ensure the appropriate distribution of funds. Stakeholders also urged increased funding, recommending a 15 percent budgetary allocation to the education sector in the state.

Improvements to educational development in Enugu State depend on teacher recruitment processes and policies, which are key drivers of student enrolment, retention, and completion rates as well instructional quality. For schools to remain functional, the government should review the teacher recruitment process to focus more on qualifications rather than affiliation to recruitment personnel or government officials. Stakeholders in Nsukka LGA recommended that teachers receive at least three training sessions in one academic year. In Nkanu West, stakeholders recommended that teachers should be trained once per term to improve teaching performance, while in Udi LGA, it was recommended that teachers should be trained at the end of each term.

A mix of theoretical and practical teaching methods is more feasible in smaller classes and statistical studies have found that smaller class sizes lead to greater student achievement in Global South countries. A lower student to teacher ratio can also help reduce teacher workloads and allow for more individualised instruction. In the RISE Summit in Udi LGA, stakeholders suggested that a target of 25 students per teacher would improve educational outcomes. Summit attendees in Nsukka called for an even lower ratio of 20 students per teacher.

School Based Management Committees (SBMC) work to increase the involvement of communities in education, which can help improve the quality and effectiveness of schools. School education committees can serve as instruments for monitoring and evaluating schools, teachers, and students’ access to and quality of education. These committees fast-track government inputs—tangible and intangible—into the education system at community levels. A government representative at the Education Summit in Udi LGA promised to reactivate the local SBMC as suggested by stakeholders, in a bid to improve educational outcomes.

Students suffer severely when teachers are absent or inefficient at executing required responsibilities. Academic and non-academic school staff should be incentivised beyond monthly remunerations to improve performance, and teachers’ punctuality and professionalism should be rewarded. Available education committees could assist in setting up this system. Government and the private sector should collaborate in sponsoring this system to help guarantee a longer-term vision. The system should reward students’ performance in line with standards set by the national Nigerian Education Policy.

Access to and quality of education are greatly hampered by inadequate teaching and learning materials. Attendees at a RISE Education Summit in Enugu State suggested an additional provision of a minimum of 200 chair-desks across all schools in Enugu. In line with the Summit’s suggestion, education committees should assist school management in ensuring proper maintenance and by providing a comprehensive list of under-resourced schools. Stakeholders also suggested government partnerships with communities focused on infrastructural improvement.

Disruptions of school activities by cultists (for example, consumption and abuse of hard drugs, violent displays, and loitering around the school environment) harm students and teachers alike. School environments need to be properly fenced and provided with security personnel. A key stakeholder in Udi LGA, Pastor Charles Ezenyi, acknowledged the need for fencing the 91 primary schools in the LGA. Local law enforcement agents should help support school security alongside the government and private bodies.

Investments in schools can only be sustained alongside corresponding investments in teachers and school-aged students. Providing schools with up-to-date knowledge is a crucial aspect of the education system. To ensure this, periodic and regular teacher training and development programmes will go a long way to improving learning outcomes. It is important to develop venues for head teachers to share experiences with younger teachers, and for quality assurance officers to take stock of teacher performance and skills.

Water, sanitation, and hygiene infrastructure is a prerequisite for both safety and the provision of high-quality education. These infrastructures should be improved immediately.

Improving basic education is a key a priority for Nigeria’s socioeconomic development. Nevertheless, investment in basic education has continued to lag in terms of budgetary allocations and priority. Evidence-based recommendations were drawn from the RISE political economy research project in Enugu State, which conducted field surveys to obtain primary information on education issues. Stakeholders indicated that poor supervision, an absence of education committees, a porous education system, and the lack of adequate water and sanitation are among the key education challenges in Enugu. The project culminated with RISE Education Summits, in which local education stakeholders and government officials gathered to discuss education policy and identify opportunities for improvement. Summit attendees recommended improved government supervision, the recruitment of qualified teachers, lower student teacher ratios, improved infrastructure, reinvigorated school education committees, a modern curriculum, and investment in WASH infrastructure and maintenance.

The Summit proceedings elicited a positive response from participating government officials and other education stakeholders, who promised reinforced commitments to the education sector. A crucial takeaway from the Summits was the pledge by government representatives to ensure that teaching becomes tailored to realistic values. Finally, agreements were reached between local stakeholders and government officials to ensure teacher development in various aspects of perceived deficiencies.

Perhaps the greatest takeaway from the Summit was the example of political leaders and education stakeholders sitting together to have a constructive dialogue about improving education in Enugu State. Even in cases where problems and policy solutions are identified, political economy considerations and misaligned incentives can lead to a lack of execution. The RISE Nigeria team believes that increased deliberative dialogue between government officials and local education stakeholders can help overcome these barriers.

Ogwuike, C.O. and Iheonu, C. 2021. Stakeholder Perspectives on Improving Educational Outcomes in Enugu State. RISE Insight 2021/034. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-RI_2021/034