Insight Note

RISE in Vietnam: Research Overview (Technical)

The team will look at how Vietnam performed better than developed countries on international assessments to understand what worked (and didn't work) in their context, how it worked, and what lessons can be learned that can be applied elsewhere.

Principal Investigators: Dr Paul Glewwe (University of Minnesota), Dr Joan DeJaeghere (University of Minnesota), DrLe Thuc Duc (Centre for Analysis and Forecasting and Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences, Young Lives)

Other Key Researchers: Pedro Carneiro (University College London), Hai-Anh H. Dang (World Bank), Sonya Krutikova (Institute for Fiscal Studies), Jonathan D. London (Leiden University), Caine Rolleston (University College London), Phung Duc Tung (Mekong Development Research Institute)

Key institutions: University of Minnesota, the Centre for Analysis and Forecasting, the Vietnamese Academy of Social Sciences, and the Mekong Development Research Institute

Other Affiliated Institutions: the (UK) Institute for Fiscal Studies, Leiden University, University College London, the University of Oxford, and the World Bank

It is not often that we can motivate a study of education in a developing country because they are doing so well. Vietnam is that success story. In the span of 25 years, Vietnam went from one of the poorest countries in Asia with abysmal living standards and stagnating educational attainment to one of high growth rates and impressive educational outcomes: Vietnam’s 2012 PISA scores in reading and math surpassed those of many developed countries, such as the US and UK, and exceeded those of many other developing countries by more than a standard deviation.

At this time, when we are facing a learning crisis in the world, it is crucial to look at the Vietnam case and understand what worked in their context, and how it worked, and what lessons we can learn that can be applied elsewhere. Furthermore, we must also understand what did not work in their drive to remarkable gains in education – it is commonly understood that the great improvements were not uniform across all socioeconomic strata, ethnic groups and regions in that country. While increasing financing and decentralization have been initiatives of the government, how they have been implemented across provinces is variable. Further study is warranted to understand how governance has supported or impeded academic outcomes. In short, Vietnam is an opportunity for much research to be done, both in lessons for other countries and for sustainability of the success story within Vietnam itself.

The team will examine the institutional reforms and understand what levers of support existed that made such an extraordinary change possible. They will look to understand what Vietnam’s Theory of Change was, and how it came to work, and in what ways it did not work.

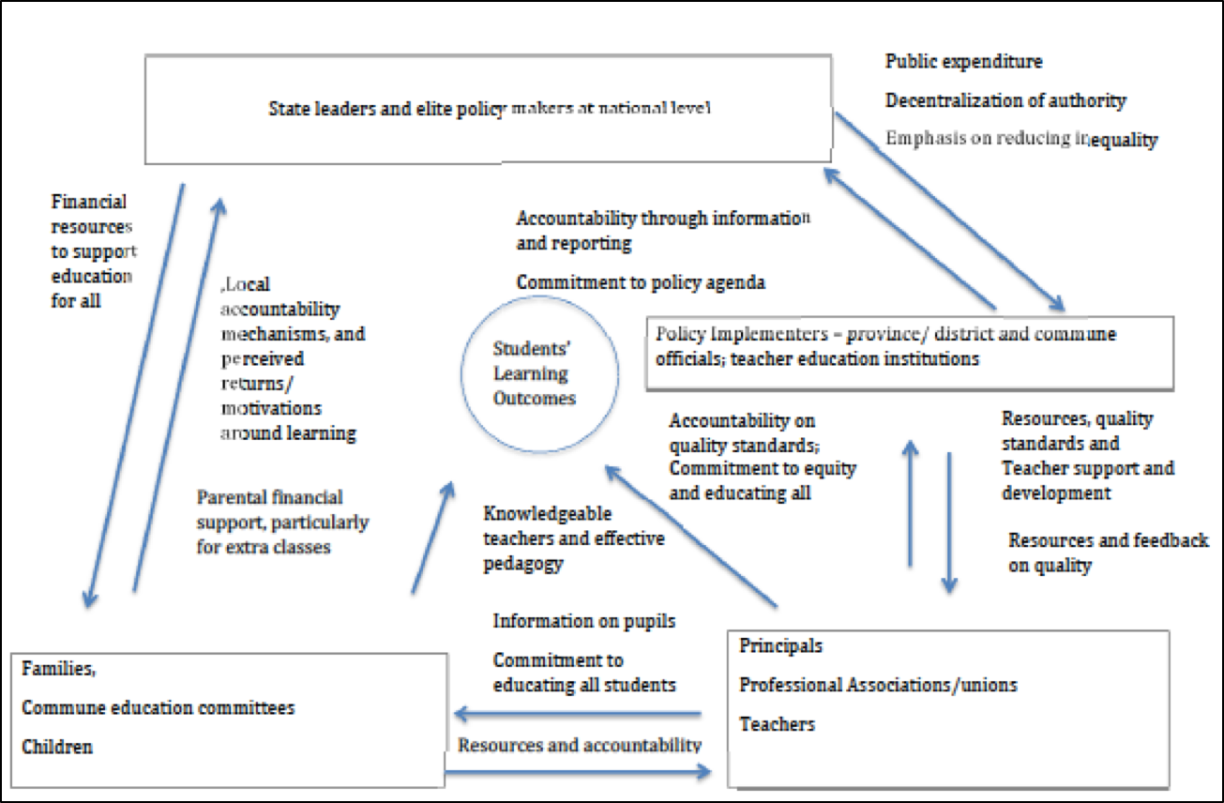

The research plan will start with a diagnostic phase that will seek to establish which elements and relationships within Vietnam’s education system induce actors (government, education and party officials, as well as teachers, principals and parents) to act in ways that produce learning, and where gaps in learning persist. The diagnostic exercise will include a mapping of de jure system structures as well as de facto characteristics of principal-agent relationships for key design elements (i.e. delegation, finance, information and motivation) across each relationship of accountability. Figure 1 shows a framework of the actors and relations of Vietnam’s education system as it relates to student learning.

In particular, several distinctive features of Vietnam’s governance and economy will inform the analysis of the education system. These include (a) the presence of a one-party state with no direct elections; (b) a decentralised fiscal and administrative system; (c) rapid urbanisation and increasing rural to urban migration; (d) the absence of independent teacher unions; (e) pervasiveness of opaque formal and informal fee structures and shadow education; (f) a trained and well-regarded teaching force with little autonomy; (g) an engaged civil society.

One key step in the diagnostic phase is digging deeper into the PISA data to certify whether it suffered from any sampling bias, for example, from selection of participating schools. Importantly, the team will also check the results of ethnic minorities vis-à-vis other students and provide an assessment of whether these groups perform less well in Vietnam’s education system.

Question 1: How did Vietnam achieve high enrolment rates and high learning outcomes?

The reforms to be studied are the following:

| Reform# | Description | Date enacted | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Increased public finance, along with the encouragement of household contributions for education. | Early1990s | Financing and Resources |

| 2 | Increased access to schooling through the construction of new schools in each commune and reducing/eliminating fees | 1995 onward | Equity, Financing and Resources |

| 3a | Fiscal and administrative decentralisation | 1996 onward | Governance |

| 3b | Increased school autonomy | 2002 onward | Governance |

| 4 | Introduction of school quality standards and assessment | 2009 onward | Information/ Governance |

In addition to studying the impact of these reforms, the research will analyse the impact of other school level factors, as well as family and child characteristics, on student performance.

The team’s preliminary Theory of Change posits that there are 8 major factors that likely played a role in producing high levels of enrolment and student learning: 1) political commitment; 2) decentralisation and autonomy at all levels of the system; 3) strong accountability relations and financial support; 4) high levels of commitment by parents and students; 5) high income growth for parents; 6) teachers’ commitment; 7) state and educational managers’ commitment; 8) civil society engagement in the education discussion.

Question 2: What impact will the new reforms have?

Vietnam is currently implementing several major initiatives to make further progress in enrolment and learning outcomes. A decision in 2012 outlining the strategy for 2011-2020 stipulates that at least 20% of the state budget must be spent on education. Two important reforms from this same decree are the following: a) Escuela Nueva programme and b) a system-wide curriculum reform. The research in this part of the project will cover three specific areas:

1) quantitative analysis to estimate the impact of the reforms on learning outcomes;

2) qualitative analysis of teacher skills (including pedagogical content knowledge, pedagogy and classroom practices), and their implementation of the new curriculum;

3) accountability analysis and implementation record.

The research approach is summarised in the figure below.

Inception-phase System Diagnostic |

| Research Focus 1 | Research Focus 2 |

| What Vietnam got right (and not so right), how, and why, in achieving its high learning outcomes | Impacts of current and upcoming system-wide pedagogical and curricular reforms aimed at further improving learning |

| Quantitative analysis drawing primarily on existing data sets, but also on new data sets (for structural estimation) | Quantitative analysis drawing on existing VNEN data sets and on new data sets to extend the VNEN analysis and to evaluate the impact of the proposed curricular reforms |

| Retrospective analysis of system coherence/incoherence of accountability relations employing mixed methods, using of both secondary and original data collected through interviews and case-based research | Qualitative research of teacher educator, school (principals) and teacher practices using the new curriculum |

| Analysis of current system coherence/incoherence around learning through study of system-wide pedagogical and curricular reforms, employing mixed methods and data from interviews, surveys and case-based research |