Alec Gershberg

University of Pennsylvania

Insight Note

Politics is not the obstacle; it is the way change happens.

David Hudson, et al

Development Leadership Program

Just as the formation of nations has been a highly contested process, so, too, the construction of systems of instruction has been marked by frequent conflict. This is not surprising: Given the central role of schooling in meeting conditions for societal survival and in the production of freedom, any method that is compulsory and spends public funds is likely to be controversial.

Ernesto Shiefelbein and Noel McGinn

Learning to Educate (2017: 315)

Over the past 50 to 75 years, most developing countries have greatly improved access to education, including for the poor. But few have made significant gains in learning as illustrated, for instance, by international standardised assessments of student achievement such as PISA, PIRLS, and TIMSS.1 In regards to the rate of improved learning, 'sustainability' is an empty catchphrase without meaningful (and in many cases) dramatic improvement in learning. Most analyses have attributed poor learning outcomes in developing countries to their proximate causes: inadequate funding, human resource deficits, poor curricular development, perverse incentive structures, poor management, and the like (Rosser, 2018). Along these lines, the RISE Programme is a seven-year research effort that seeks to understand what features make education systems coherent and effective in their context, and how the complex dynamics within a system allow policies to be successful. RISE has Country Research Teams (CRTs) in seven countries: Vietnam, Indonesia, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Nigeria, India, and Pakistan.

Recently, however, some analysts have suggested that the determinants of learning lie more in the realm of politics and, in particular, the interests of state elites. True sustainability in educational improvement will hinge greatly on understanding the political economy of education reform (e.g., how contestation between competing political and social elements influences and constrains outcomes) and in aligning reform design and strategies with what is known about political settlements, the governance and politics of education, the actors and domains of contestation in an education system, and the structural and institutional drivers of reform.

Pritchett (2018), for instance, has hypothesised that state elites in developing countries have been more interested in using education systems to promote nation-building objectives such as the use of a national language and commitment to a prescribed national identity than economic or social objectives. Similarly, Paglayan (2018) has argued that state elites in Western Europe and Latin America established or expanded national education systems primarily in order to enhance their political control over populations, noting that educational expansion often occurred in the wake of periods of widespread violence. In both cases, these scholars have suggested that improved enrolment rates have served elite agendas better than improved learning outcomes; the latter have, at best, been irrelevant and, at worst, antithetical to these interests.

As part of this larger effort, RISE has constituted a Political Economy Team (PET) with a programme of research to test these ideas, refine them, and generate new ideas about the link between politics and learning outcomes in developing countries by analysing a set of country cases. This Political Economy Team works along two primary dimensions:

PET-A and PET-I are distinct research efforts, although they are part of the same intellectual endeavor. Some coordination and intellectual exchange will be required to ensure the success of the overall RISE PET as part of the broader RISE Programme, but the extent of this coordination will be mostly limited to one or two synthesis papers.2 Throughout this paper we focus on PET-A and refer explicitly to PET-I when relevant.

For PET-A, all seven RISE countries (Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Tanzania, and Vietnam) will be cases that we will refer to alternatively as 'deep dives' and Political Economy Country Studies.3 The programme involves three main components:

In addition to the deep dives, we will add shorter, less expansive case study papers on some non-RISE countries from Chile, Peru, Kenya, South Africa, and Egypt. Each case (both in RISE and non-RISE countries) will be led by a Political Economy Country Study Lead (PECS Lead), whose Terms of Reference will be guided by and built upon this paper.

This paper develops the Guiding Principles for the RISE Programme’s PET-A research projects. It also begins to lay out a draft conceptual framework for the RISE Political Economy Analysis (PEA) of education reform, and discusses how the research itself should help flesh out that conceptual framework over the next couple of years. We describe an approach for the various research projects rather than a method, particular theory, or set of theories that will be tested. Throughout, we have a particular focus on the 'politics of learning', or the politics of educational strategies, policy design, and implementation processes and how they affect the long-term potential for developing countries to improve education quality and cognitive skill development at (in many cases) drastically improved rates.

A core question at the heart of this effort is, “Why do some countries adopt and successfully implement policies that improve learning, but most do not?”4 In this sense, the RISE PEA builds from a substantively different starting point than many of the frameworks more commonly used in the development community. That is, most educational PEA focuses on strategy in policy design and implementation once the overall policy goals have been set—in fact, often once the actual contours of an intervention have been designed. The RISE PEA first seeks to understand the origin of intent. To be sure, the origin of the intent, the implementation strategies, and politics of education reform are all deeply inter-related and affect each other. Whatever the origin of intent, it will be impacted by many forces and experiences, including the past and present political contestations. What induces a government to take learning goals seriously is likely to be closely tied to what strategies have been effective and how leaders and policymakers conceptualise and mean by 'learning'. Fully disentangling these separate elements is not truly possible.

Of course, a government must have the capacity to deliver on its intent. We do not deny the crucial role of capacity and strategy, but we note that many, if not most, development efforts (especially donor-led) focus too early and too much on government capacity and political strategies while making naïve assumptions about the nature of intent. One such assumption is that government policymakers are benign and share the objectives of the donor agencies and institutions. While convenient and even necessary for policy dialogue and design, we know this assumption is often false.5

Following Pritchett (2018) we argue that understanding how educational change happens will ultimately require a political economy approach that describes the motivations and behaviour of governments and policymakers. We can then begin to build a model that adequately address at least three key facts about basic education policies over the course of, roughly, the past 75 years:

There is no shortage of models and theories of the political economy of education reform. We reviewed many of the leading efforts and conclude that while they may lend many important insights on the politics of education reform, none to date can adequately answer these three questions, let alone the larger driving question of why and when countries adopt and successfully implement quality-enhancing, learning-oriented reforms. Some lines of thought, such as the 'political settlements' literature are excellent at examining the deep, underlying contextual forces that drive and more importantly constrain the policies a government might pursue (See for instance Levy [2018], Hickey and Hossein [2018], or Kelsall [2016] among others). But at least in terms of future policy design and strategy, the political settlements approach is often better at lending insights on the possible (and impossible or unwise), on the why rather than the what of what policies governments might actually adopt specifically to improve learning in a particular country context. Nor does the political settlements approach fully address the three motivating facts above; it is, in short, at least helpful and perhaps necessary to understanding the politics of learning, but not sufficient.

Other strategies focus on stakeholder analysis, which is of course a critical component but often either takes as its starting point what the government wants to adopt—rather than why it wants to adopt it—or ignores the deeper cultural, political, and societal contexts and divisions. Such approaches are common in the large international development organisations. (See for example Kaufman and Nelson [2005], Grindle [2004], Kingdon et al [2014] or Bruns, Harbaugh and Schneider [2018]). We seek to build a conceptual approach for PEA that finds the 'sweet spot' between these literatures and that, concomitantly, will work for the seven RISE country programmes already underway, while providing insights for how to undertake similar work in other country contexts, and also facilitate cross-country insights.

The heterogeneity of the RISE CRTs and their research foci capture some of the tensions inherent in finding a common conceptual framework. However, at an internal workshop lead by, and based on the work of, Brian Levy (2014, 2018) key members of four out the seven CRTs revealed considerable support for incorporating at least some work derived from the political settlements literature.7 The concept of a political settlement is “‘the balance or distribution of power between contending social groups and social classes, on which any state is based.’” (di John and Putzel 2009: 4 in Hickey and Hossain (2019); See also Kahn (2010))

At least as a starting point for a deep dive into the politics of educational reform in any given country context over a period of several decades, Kelsall (2016: 2) provides the following useful working concept of political settlement:

....while different authors and organisations have defined ‘political settlement’ in slightly different ways, there is increasing convergence around the idea that [Political Settlement Analysis] PSA is about understanding ‘the formal and informal processes, agreements, and practices that help consolidate politics, rather than violence, as a means for dealing with disagreements about interests, ideas and the distribution and use of power’ (Laws and Leftwich, 2014: 1), and that these will play out across two levels, involving both intra- elite and elite-non-elite relations (Laws, 2012). A major implication of PSA is that, since replacing one political settlement with another is normally a very difficult or risky business, successful development practice involves some kind of adaptation to these formal and informal processes, practices and power balance, and their associated path-dependencies.

Building on Levy (2014, 2018) and Hickey and Hossain (2108) we briefly outline a typology of country-level political settlements that each of the deep dives will examine as a starting point. We recognise that the deep dives will also be heterogeneous and do not wish to overly define a method or strict framework that each must follow. However, we believe that starting with a goal to examine the politics of learning in each country context using this conceptualisation of political settlement will provide a kind of baseline comparative foundation upon which to build comparisons across countries (while also yielding useful insights regarding the politics of learning).8

Levy (2018) argues that a great deal of insight can be garnered from delving into three key variables:

Thus, Levy (2018: 13-14) classifies political settlements “according to whether their configuration of political power is dominant or competitive, and whether the institutional rules of the game are personalised or impersonal.” This two-fold distinction generates four ideal types of political settlement. Operationalising these variables yields at least two useful '2 by 2' classifications of four potential kinds of political settlement and four potential kinds of public governance.

| Dominant | Competitive | |

|---|---|---|

| Personalised | Elite cohesion is high, power exercised top-down by leadership, limited constraints on political actors. | Elite cohesion is low, settlement demands power change hands on electoral competitive basis, but 'rules of the game' are personalised |

| Rule-of-Law | Elite cohesion is high, power is top-down, but actions are anchored in rules which institutionalise how power is to be exercised. | Politics is competitive, impersonal rules govern the exercise of power. |

Source: Pritchett 2019, Review Essay

| Hierarchical | Negotiated (Horizontally) | |

|---|---|---|

| Personalised | Implementation is hierarchical, a principle-agent structure, but agent compliance is based on personalised authority of the leadership, not a system of rules. | Neither formal rules nor well-defined hierarchy of authority are in place. Such agreements to cooperate as may emerge (and they may not) depend on the specific people involved. |

| Impersonal | Classical “Weberian” bureaucracy of top-down enforcement of impersonal rules and standard operating procedures. | Multiple stakeholders, each with significant independent authority, agreed on how to work together, and codify these agreements in formal, enforceable rules. |

Source: Pritchett, 2019, Review Essay

Naturally, as with any stylised heuristic, dichotomous distinctions are conceptually helpful but rarely truly dichotomous in practice. Country contexts do not fit neatly into one category, but more likely have a dominant or overarching category with some aspects of some or all of the others. Each Political Economy Country Study Lead will need to decide how to resolve this issue. For example, Levy (rather optimistically) and Pritchett (rather more pessimistically) both discuss the potential for assigning rough percentages or weights to each of the four kinds of political settlement and public governance.9

We have, overall, refrained from 'buying' the political settlements wholesale; for example, we do not assert that the political settlements approach can yet be used for prediction, but do hope that at the end of the RISE PET work, we are closer to a framework that may be used for prediction. Rather, the decision to use the political settlements literature as a starting point is based on a few inter-related concepts/issues:

An important related determination for each deep dive research team will be how to define the social groups or actors who impact the political settlement in each case (and how they may change over time). Taken together, these social groups are referred to as the Social Foundation. Henstridge, Lee and Salam (2019) note that:

… social foundations and social norms can be extremely persistent, and can constrain the institutional options for political leaders: a king who runs the army and the police may still find it impossible to introduce rules and practices that violate very widespread social norms. And yet, even social factors are persistent rather than permanent – economic outcomes that change lives and livelihoods, like literacy and urbanization, can shift social conventions and norms.

Kosack (2012) provides a useful discussion of how political leaders determine which groups hold sway in the social foundation over their ability to stay in power (whether in a democracy or not):

If leaders were free to pursue policies of their choosing, then, perhaps, their policy choices could be explained by the differences of political will, knowledge, or morality. But leaders are not free to choose what policies to pursue. The rule at the pleasure of a particular set of citizens—selected voting blocs or certain business elites, landowners, workers, or other economic, social, religious, or ethnic communities. (Kosack 2012: xi)

Furthermore, it may be possible for some or all of the deep dives to use and/or test Kosack’s hypothesis that a successful politics of learning will involve what he calls a “political entrepreneurship of the poor,” whereby organisational structures are developed to allow poor citizens to become a group in the social foundation and thereby to act collectively to support or contest the government and its leaders.10 This implies an additional challenge for the RISE deep dives, namely assessing the nature of the political settlement and social foundation at the outset of the chosen reform time period (generally several decades) and determining if and how they evolve over the time period.11

Any such effort will necessarily consider a range of elites (many of which will be closely connected to what would be in a more typical stakeholder analysis). Yet, as part of the exploration of political settlements in RISE countries, we will encourage the deep dive teams to pay close attention to a relatively smaller group of political leaders. For example, the Development Leadership Program (DLP) has for more than a decade pursued a line of research that could prove helpful. They have argued that in fact “effective leadership and collective action of a relatively small number of leaders and elites, across the public and private sectors, are essential for building effective states.”12 Acknowledging that effective political processes “involve diverse leaders and elites, representing different groups, interests, and organisations, tackling a series of collective action problems in locally appropriate and feasible ways,” they argue that the “quality and quantity of leaders and elites with the necessary vision, knowledge, and experience” are often quite limited.

This could help bound the inquiry, though will be more appropriate for some cases than others. For instance, these concepts dovetail well with the recent proposals by the Tanzania CRT (Studies 8 and 9) which explores: “Under what conditions do coalitions for policy reforms emerge in a hegemonic party state? And what explains the rapid collapse of political support at the highest levels of the Government of Tanzania for BRN?”13 On the other hand, such a focused approach may prove less fruitful in a case like Vietnam with a seemingly more diffuse political elite primarily operating through the Communist Party.

It is important to note that these conceptual guideposts for the deep dive studies identify an approach and guiding principles but not a methodology or set of methods. Aside from the likelihood of doing elite interviews and some historical analysis, the political economy analysis and methods for each country case study are to be chosen and defined by the Political Economy Country Study (PECS Lead), each of whom may come from different disciplines and/or research traditions.14

Nor are we picking a particular theory to test. In fact, we would argue that the varied traditions and methodological orientation of the different researchers for this PET-A work make devising a conceptual framework for analysing the politics of education reform in developing countries complicated at best and potentially unhelpful because it potentially requires us to prioritise a particular tradition of analysis within political science and associated ontology and cast aside others. There are multiple ways of understanding the politics of policy-making in developing countries and they are not really compatible with one another because they presume/emphasise a different unit of analysis (e.g., the rational utility maximising individual in the case of neoclassical political economy/public choice theory, institutions in the case of the various strands of institutionalism, intra-bureaucratic cliques in Weberian patrimonial state analysis, class in the case of Marxist analysis, interest and other groups in the case of pluralist analysis, and individual politicians in the case of elite-centered analyses [Grindle and Thomas’ 1991 classic textbook on the politics of policy-making in developing countries is good on these distinctions]). The political settlements framework overcomes these issues to some extent by eliding the whole question of the unit of analysis—it emphasises the importance of power relationships and coalitions but doesn’t specify whether these relationships/coalitions are between individuals, classes, groups, cliques, or something else. This is perhaps one of the reasons this approach has proven so popular—it has allowed diverse groups of scholars working on donor-funded pieces of research to imbue it with their own preferred understanding of politics, avoiding the need for, say Marxist scholars, to work within a Weberian mode of analysis and so forth.

An initial research effort by such a diverse set of analysts to understand and categorise the variety of political settlements across RISE country contexts seems likely to yield important insights regarding the origin of, and constraints on, the intent of governments to improve learning outcomes. It will certainly not yield a generalisable (or testable) theory of the politics of learning as Pritchett (2018) calls for, but it should contribute to our ability to work towards such a theory.

As is clear from the discussion above, we expect research teams to work within a set of broad Guiding Principles while giving them considerable latitude regarding how specifically to design and carry out their research methods and plans. However, to provide greater guidance and better ensure enough comparability across cases for integrative and comparative analysis, we further developed some specific parameters within which we expect the teams to work (unless they explicitly make a case otherwise).15

Much analysis of education policy-making processes has been informed by what Paulston (1977) and others (e.g., Ginsburg et al, 1990; Arnove, 2009) have labeled the 'equilibrium paradigm'. This paradigm portrays education policy reform as either part of a natural and inevitable process of progression from tradition to modernity in accordance with an underlying logic of increasing rationality (the evolutionary variant) or a functional response to system imbalances or societal needs in accordance with an underlying logic of system maintenance (the structural-functionalist variant). In both cases, it suggests that society is essentially consensual in nature and that education policy-making is a seamless and apolitical process driven mainly by technical educational and economic concerns. By contrast, and consistent with the Guiding Principles laid out in this paper, the deep dives and to some extent the non-RISE country case studies will apply a conceptual framework for analysing education policy-making that comprises the following main elements:

While the specific range of policy areas to be explored will be determined by the research teams, to increase the likelihood the PET-A work will yield results that lend themselves to comparative work across countries, the research teams are attending to two key policy areas to drive part of the work.16

Again, these foci do not preclude any case exploring other policy areas in greater detail; rather, it is a commitment to explore these two policy areas in enough detail to allow some comparison across cases. The idea is that this encourages the political economy work to be problem driven. By paying some attention to these issues throughout the case, and the politics of their development over time, the specifics will cascade outward and reveal the political economy in a way that enlivens the political settlements work, and that will make it more useful to current policymakers. It also is likely to cascade outwards to intergovernmental (or multi-level) issues.

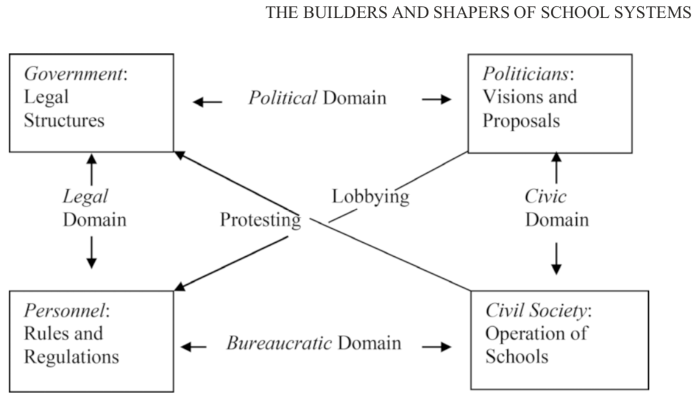

Shiefelbein and McGinn (2017) provide a simple framework for the domains of contestation in education systems that we propose to use as a bridge from the examination of political settlements to the inevitable stakeholder analysis of PEA. Figure 1 (Figure 23 in Shiefelbein and McGinn [2017]) is a stylised representation of the four domains of contestation.

Source: Learning to Educate, Shiefelbein and McGinn (2017)

The framework is useful on several levels. First, it serves as a check to make sure that the political settlement inquiry is fully covering the key areas for potential contestation and understanding what induces a government to take learning seriously. Second, each CRT is focusing more on some of these domains than others; thus being thoughtful about each of these domains may reveal some blind spots in their lines of research with respect to understanding the politics of reform. And third, there may be some potential to understand how differences in the domains of contestations play out in terms of adoption of quality-enhancing reforms.

Discussing these Domains of Contestation might be done as part of the political settlements analysis or separately. Again, exactly how to do so is up to the individual Political Economy Country Study Leads to conceptual and propose.

Asking the question, “How are political conditions fostered that put policies to improve learning at the centre of an education system?” immediately begs another, “How do we know what these polices are?” Do we predetermine them before beginning the political economy analysis or are we open to the possibility of multiple possible solutions to the problem of learning?

Clearly, it will be crucial to successfully examine the means of determining if and how (and why) we believe one country (say Vietnam) intended to improve learning and did so successfully while others (say Nigeria or Pakistan or Indonesia) either did not try or tried but were not successful. This gets at what the growth diagnostics analysts such as Pritchett call the “full trinity”: that an action should be technically correct, politically supportable, and administratively feasible.

With the foundation of the political settlement analysis, and augmented by some consideration of the domains of contestation, each deep dive will also do some of the kind of traditional stakeholder and interest group analysis that, as discussed above, is more commonly the first step in (and the heart of) political economy analysis. Shiefelbein and McGinn’s framework for describing domains of contestation also yields a useful way to conceptualise stakeholders in terms of their relationships to the education system. Specifically, they see the education system as a source of different kinds of benefits to different groups of stakeholders and argue that some generalisable tendencies may be discernable from the nature of the relationship stakeholders have with the systems. Table 1 (Table 19 in Shiefelbein and McGinn’s framework) below provides a categorisation of stakeholders as 'users', 'operators, and 'suppliers' of the school system.

There are, of course, any number of frameworks for stakeholder analysis. Another useful one (at least to examine how adopted policies succeed or fail in getting implemented) is Bruns et al (2018), which is heavily focused on teacher unions and other teacher-oriented stakeholder groups.21 There may be scope to examine, in each or some of the PET deep dives, their “six interrelated issues in design and implementation that have been important to reform success: consultation, sequencing, compensation, negotiation, communication, and sustaining reforms.” (Bruns et al, 2018: 34)22 Appendix A presents Kingdon’s (2014) "Theory of Change" for political economy analysis of education, primarily because it provides a very complete list of stakeholders one might consider.

One common pitfall to avoid (and even challenge) in such stakeholder analysis, identified and fleshed out by Rodrik, is the “notion that there is a well-defined mapping from ‘interests’ to outcomes.” (JEP, 2014: 190). It would seem useful to incorporate insights from Crouch and DeStefano’s (2006: 9) analysis of how to overcome political the messiness and unpredictability of implementation.23

“Since most development projects pay attention to the technical aspects of reform, we leave those aside. Conversely, since most projects fail to address the process and politics of reform, it is on those that we focus. In particular, ERS concentrates on the political and institutional dimensions of reform. We touch on leadership, institutional capacity, resources, and civil society issues, but within the context of how one uses them to define, advocate for, advance, and carry through reforms in the face of political and institutional obstacles.”24

| Users | Operators | Suppliers |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Source: Learning to Educate, Shiefelbein, and McGinn (2017)

It is beyond the scope of this paper to do a priori a complete integration of the full RISE accountability framework and the 5x4 matrix with the approaches outlined above. In fact, we believe this integration has evolved over the course of the deep dives and that the PECS Leads will together with the PET-A Lead have begun to fill out how the PET work dovetails with, and even impacts, the theory of change implied by the RISE 5x4. It is, however, necessary to draw connections between the political phenomena studied through the PET-A and at least selected relevant components of the accountability framework in each case. That is, as the CRTs begin to draw insights about system (in)coherence through their overall research efforts, we seek to make connections to the political economy work undertaken through the PET and mine it for potential insights.25

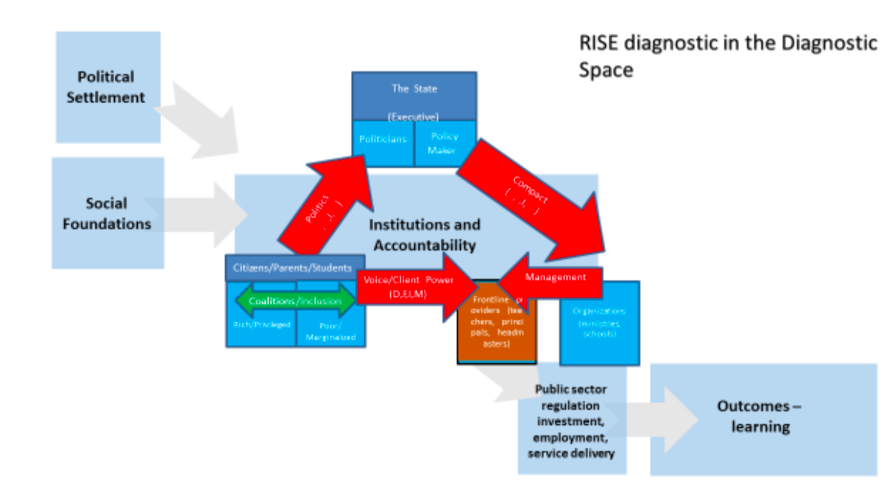

In a recent OPM working paper Henstridge, Lee, and Salam (2019) develop 'Thicker Policy Diagnostics' for economic growth and provide an excellent visualisation for how the political analysis outlined above could be integrated with the RISE 5x4.

Source: Mark Henstridge, Stevan Lee, Umar Salam 2019

This visualisation is, however, deceptively simple and clear compared to the actual challenges faced, not the least of which is that as complex as growth diagnostics are, the causal pathways that lead from policy to growth are more well understood and “agreed upon” than those that improve learning. In addition, while only one of the “sides” of the accountability triangle is called “Politics”, there are political economy dynamics in each of the myriad relationships through the triangle and 5 by 4. We might start by taking the 5 by 4 matrix and transforming it in the manner that the growth diagnostics extrapolated what it would look like if any given reason for low private investment were a binding constraint to growth, as shown in Table 4.

| Conceptual Question | Evidence | Evidence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Politics (citizens as principals, politicians as agents) | Delegation | If 'weak delegation' were the binding constraint to a politics coherent for learning outcomes this is what we would expect to see… | ||

| Finance | If 'weak finance' (level or structure) for education were the binding constraint to a politics coherent for learning outcomes this is what we would expect to see…. | |||

| Support (?) |

NA (?) |

|||

| Information | If 'weak information'… (etc) | |||

| Motivation | If 'weak motivation'… | |||

| Row coherence (e.g., DFSIM within politics not coherent) | If 'row incoherence' within politics were the bc to a politics coherent for learning outcomes, of the following types (D and I incoherent (e.g. delegation is broad, I narrow, D ambitious but F limited, I out of timing to make learning salient for M) | |||

| Column coherence (e.g., D across P, C, M, CP not coherent) | If 'D' incoherent, 'I' incoherent etc. | |||

| Compact | D, F, S, I, M | |||

| Management | D, F, S, I, M | |||

| Client Power | D, F, S, I, M |

This structure makes it clear that lots of 'PEA' are really about the other elements of the 5 by 4 (e.g., essentially the politicians are the principals and others are the agents/actors in what the framework calls 'compact'). In addition, 'management' and agenda-setting make salience to this issue an electoral (or settlement) success.26

At the moment, we are productively headed towards creating, though not filling out, this matrix (i.e., what are the empirical counter-parts of the concepts of 'weak delegation' or 'weak political commitment to learning outcome goals' [which is the endogenous outcome?]).27

The PET-A Lead and Research Directorate are working with the PECS LEADS and relevant CRT members, and together seek to fill in the above table via the approaches and plausible tools outlined here and in the PECS research proposals for each deep dive. One goal is to determine the ways in which the elements of accountability differ by type of political settlement, or at least if the political settlement analysis provides insights into the ways accountability functions or not.

We have also encouraged the PECS to examine the role of leadership, which in some ways stands the whole 'accountability' triangle on its head. That is, authoritarian (totalitarian) governments see the citizens as accountable to the state and not particularly vice versa.

Many of the research efforts underway or proposed by the CRTs hold potential to elucidate specific aspects of the overall PET-A framework. Although we would obviously not be able to undertake similar studies in each of the seven CRT countries, we will use, and in some cases work with the CRTs to carry out, work. Just a few examples would be:

While not central to the approach we have developed for the political economy analysis deep dive cases, it may be helpful for the deep dives to reflect upon and look for insights into the nature of education as a public good and the extent to which learning is prioritised over, say, socialisation or nation-building by political leaders. Building upon connections Pritchett (2018) draws to Mark Moore’s RISE working paper (Moore, 2015) in which the nature of education as an a-typical 'public good' subject to an arbiter of public value is explored, it may be worth considering the following framework developed 15 years ago by Mitchell and Mitchell (2003).28 Their framework makes clear that differences in how different stakeholders see the aims of an education system can lead to very different motivations for supporting or blocking key reforms. They also make clear (as does Pritchett) that neither economic forces nor (perhaps as a consequence) economists can explain even half of the trends in expansion, let alone the means of production as large, publicly-controlled Weberian bureaucracies.

A Framework for Analysing the Political Economy of Education Policy

Most of the public discourse (including within scholarly and analytic communities) revolves around education as a human capital investment and thus assumes that education is a public good whose aim is to provide technical skill development with long lasting economic benefits to both individuals and society. However, both Pritchett and Mitchell and Mitchell (2003) show us clearly that this is demonstrably often not the correct view of how or why education policies are adopted.

| What aims for education? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Who benefits? | Education as technical: training in skills of practical value having economic value | Education as culture: awakening of identity and character having political value |

|

A private good: Distributed results accruing to individuals as education is being obtained A public good: Cumulative benefits for everyone; expected to accrue interest over time |

Durable product: Durable skills and knowledge with workplace value that persists over time (lasting benefits) Human capital investment: System capacity building with some risk of not being realised by enough individuals to be worth cost |

Direct service: Safe, nurturing, sensitive, caring child rearing and decent working conditions for teachers Cultural legacy: Establishment of civic value that determines status and may lead or lag society |

Source: Mitchell & Mitchell (2003)

Mitchell and Mitchell (2003) provide the additional insights that all of the following could be at play at once: a) policy dialogues that do not adopt the rhetoric of human capital investment are doomed to failure; therefore, we should expect politicians and policymakers to adopt such rhetoric (though not because they hold the same views as economists about the nature of education as a good or the promise of education as an investment in human capital); b) socialisation (or cultural legacy) is a key motivation in the politics of education policy and this attribute directly impacts the reasons why quality enhancing reforms are or are not adopted; and c) important stakeholders and constituencies (and voters) might view education as a direct service (a consumption good) and governments may seek to please them even if these constituencies’ view is based on education being a private good—a view that does not match up with either the policymakers themselves or most of the educational research community.

This framework supports the inanity and danger Pritchett (2018) elucidates of the “normative as positive” model by which economists often explain policymaker motivations and turns the “response to political pressure” model further on its head.29 Rodrik (2014) argues powerfully the need to understand the “ideas that political agents have about: 1) what they are maximising, 2) how the world works, and 3) the set of tools they have at their disposal to further their interests.”

Indeed, as Pritchett argues, the politics of learning are likely to present so called “wicked problems” whose amelioration will require reform strategies and policy recommendations undergirded by both an understanding of complex adaptive systems and truly innovative models of government motivation and behaviour. The RISE CRT efforts should provide ample insights in this regard, which this PET-A research program should augment.

| Theory of Change | |||||

|

Underlying drivers for education reform e.g.:

⬇︎ Legitimacy and creation of political agenda ⬆︎ Underlying structural characteristics: e.g.:

|

Actors with vested interests Internal e.g.:

External e.g.:

|

Incentives that promote reform e.g.:

⚡️ Threats that resist reform e.g.:

|

Policy decisions e.g.: Characteristics

⬆︎ ⬇︎ Policy implementation |

Strategies employed To promote reform e.g.:

⚡️ To resist reform e.g.:

|

Access and quality consequences For students For schools For education systems |

Source: Kingdon et al (2014)

Batley, R. and Harris, D. 2014. Shaping policy for development: Analysing the politics of public services: a service characteristics approach. Oversees Development Institute. Retrieved from https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/8913.pdf

Besley, T. and Burgess, R. 2002. The Political Economy of Government Responsiveness: Theory and Evidence from India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117 (4). P. 1415-1451. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355302320935061

Brookes, R. and Kemp, S. 2019. “Can we actually think and work politically?” [Blog post, February 26]. Retrieved from https://www.devex.com/news/sponsored/opinion-can-we-actually-think-and-work-politically-93325

Bruns, B. and Schneider, B. R. 2016. Managing the Politics of Quality Reforms in Education: Policy Lessons from Global Experience. Education Commission Background Paper. Retrieved from http://report.educationcommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Managing-the-Politics-of-Quality-Reforms.pdf

Bruns, B., Macdonald, I. H. and Schneider, B. R. 2019. The politics of quality reforms and the challenges for SDGs in education. World Development, 118, 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.02.008

Chang, M. C., Shaeffer, S., Al-Samarrai, S., Ragatz, A.B., de Ree, J. and Stevenson, R. 2014. Teacher Reform in Indonesia: The Role of Politics and Evidence in Policy Making. Directions in Development. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/726801468269436434/pdf/Main-report.pdf

Corrales, J. 1999. The State is Not Enough: The Politics of Expanding and Improving Schooling in Developing Countries. American Academy of Arts and Sciences: 1-58. Retrieved from https://jcorrales.people.amherst.edu/promise_of_participation/images/corrales_edu%20state_is_not%20enough.pdf

Denmark International Development Agency. 2011. Applying Political Stakeholder Analysis – How Can It Work?. DANIDA Technical Advisory Services.

Dasandi, N. and Esteve, M. 2017. The Politics–Bureaucracy Interface in Developing Countries. Public Administration and Development, 37(4), 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1793

Department for International Development. 2009. Political Economy Analysis. How to Note. A DFID Practice Paper. Retrieved from https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/events-documents/3797.pdf

Destefano, J. and Crouch, L. 2006. Education Reform Support Today. USAID Education Reform Series. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2f61/5263c1031ddba7a34a0cbd86418c59f97318.pdf

Development Leadership Programme. 2018. Development Leadership: What it is, why it matters, and how it can be supported. Developmental Leadership Programme Brief. Retrieved from https://www.dlprog.org/publications/executive-summaries/developmental-leadership-what-it-is-why-it-matters-and-how-it-can-be-supported .

Di John, J. and Putzel, J. 2009. Political Settlements: Issues paper. Discussion Paper. University of Birmingham. Retrieved from http://www.gsdrc.org/docs/open/EIRS7.pdf

Dias, M. and Ferraz, C. 2017. Voting for Quality? The Impact of School Quality Information on Electoral Outcomes. Working paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association and Latin American Meeting of the Econometric Society 2017. Retrieved from http://www.econ.puc-rio.br/uploads/adm/trabalhos/files/TD668.pdf

Edwards, D. B. 2018. Global Education Policy, Impact Evaluations, and Alternatives Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75142-9

European Commission. 2008. Analysing and Addressing Governance in Sector - Tools and Methods Series Reference Document No 4. Office of Official Publications of the European Commission. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.2783/33642

Fisher, J. and Marquette, H. 2013. Donors Doing Political Economy Analysis: From Process to Product (and Back Again?). Development Leadership Programme Working Paper 28. Retrieved from https://res.cloudinary.com/dlprog/image/upload/YMiWfSVCJsRHoBID8jtwrlJOPITIsVmjOLNx5vQx.pdf

Grindle, M.S. 2004. Despite the Odd – The Contentious Politics of Education Reform. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Grindle, M.S. and Thomas, J.W. 1991. Public Choices and Policy Change. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Gulson, K. N. and Christopher L. 2014. “The new political economy of education policy: cultural politics, mobility and the market: a response to M. Peters’ ‘four contexts for philosophy of education and its relation to education policy’.” Knowledge Cultures 2, 70. Gale Academic One File.

Harris, D., Batley, R., Mcloughlin, C. and Wales, J. 2013. The Technical is Political: Understanding the Political Implications of Sector Characteristics for Education Service Delivery. Oversees Development Institute. Retrieved from https://www.odi.org/publications/7846-technical-political-understanding-political-implications-sector-characteristics-education-service-delivery

Heally III, H. F. and Crouch, L. 2012. Decentralization for High-Quality Education: Elements and Issues of Design. RTI Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3768/rtipress.2012.op.0008.1208

Henstridge, M, Lee, S. and Salam, U. 2019. Thicker Policy Diagnostics. Integration of political and economic theory and data for a different and better analysis of development challenges. Working Paper Oxford Policy Management. Retrieved from https://www.opml.co.uk/files/Publications/td-working-paper-final.pdf?noredirect=1

Hickey, S. and Hossain, N. 2018. The Politics of Education in Developing Countries – From Schooling to Learning? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hudson, D. and Leftwich, A. 2014. From Political Economy to Political Analysis. The Developmental Leadership Program Working Paper 25.

Hudson, D., Marquette, H. and Waldock, S. 2016. Everyday Political Analysis. Birmingham: Developmental Leadership Program, University of Birmingham.

Hudson, D., McLoughlin, C., Marquette, H. and Roche, C. 2018. Inside the black box of political will, The Developmental Leadership Program, retrieved from https://www.dlprog.org/publications/research-papers/inside-the-black-box-of-political-will-10-years-of-findings-from-the-developmental-leadership-program

Wales, J., Magee, A. and Nicolai, S. 2016. How does political context shape education reforms and their success? Lessons from the Development Progress project. Dimension Paper 6. Oversees Development Institute. Retrieved from https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/10808.pdf

Kaffenberger, M. 2018. “Simulating Learning: A Formal Model for Learning Profiles,” Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) blog. June 3, 2018. https://www.riseprogramme.org/blog/simulating-learning-formal-model-learning-profiles

Kaufman, R. and Nelson, J.M. 2004. Crucial Needs, Weak Incentives - Social Sector Reform, Democratization, and Globalization in Latin America. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

Kelsall, T. 2016. Thinking and working with political settlements. Oversees Development Institute Briefing, retrieved from https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/10185.pdf

Kelsall, T. 2018. Thinking and working with political settlements – The case of Tanzania. Oversees Development Institute (ODI) Working Paper 541. Retrieved from https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/12520.pdf

Kelsall, T., Khieng, S., Chantha, C. and Muy, T. 2016. The political economy of primary education reform in Cambodia. ESID Working Paper No. 58. Retrieved from http://www.effective-states.org/wp-content/uploads/working_papers/final-pdfs/esid_wp_58_kelsall_khieng_chantha_muy.pdf

Khan, M.H. 2010. Political settlements and the governance of growth-enhancing institutions. Draft Paper in Research Paper Series on ‘Growth-Enhancing Governance’. London: SOAS, University of London. Retrieved from https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/9968

Khemani, S. 2019. What Is State Capacity?. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/336421549909150048/What-Is-State-Capacity

Kingdon, G.G., Little, A., Aslam, M., Rawal, S., Moe, T., Patrinos, H., Beteille, T., Banerji, R., Parton, B. and Sharma. S. 2014. A rigorous review of the political economy education systems in developing countries. Final Report. Education Rigorous Literature Review. Department for International Development (DFID). Retrieved from http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/

Kosack, S. 2012. The Education on Nations - How the Political Organization of the Poor, Not Democracy, Led Governments to Invest in Mass Education. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kota, Z., Hendriks, M., Matambo, E. and Naidoo, V. 2018. Provincial Governance of Education—The Eastern Cape Experience. In Levy, B., Cameron, R., Hoadley, U., Naidoo, V. (2018). The Politics and Governance of Basic Education – A Tale of Two South African Provinces (121-148). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Laws, E. and Leftwich, A. 2014. Political settlements. Developmental Leadership Program Concept Brief 01. Retrieved from https://res.cloudinary.com/dlprog/image/upload/wkyZUlQEYmCzBzWvcNPt6VKCVAyKhkkCph8jTWiW.pdf

Laws, E. and Marquette, H. 2018. Thinking and working politically: Reviewing the evidence on the integration of politics into development practice over the past decade. Thinking and Working Politically Community of Practice. Retrieved from https://twpcommunity.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Thinking-and-working-politically-reviewing-the-evidence.pdf

Leftwich, A. and Hogg, S. 2007. The case for leadership and the primacy of politics in building effective states, institutions and governance for sustainable growth an social development. The Developmental Leadership Program Background Paper 01. Retrieved from https://www.dlprog.org/publications/background-papers/leaders-elites-and-coalitions-the-case-for-leadership-and-the-primacy-of-politics

Levin, B. 2012. System-wide improvement in education. UNESCO Education Policies Series 13. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311947300_System-wide_Improvement_in_Education

Levy, B. 2014. Working with the Grain - Integrating Governance and Growth in Development Strategies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Levy, B., Cameron, R., Hoadley, U. and Naidoo, V. 2018. The Politics and Governance of Basic Education – A Tale of Two South African Provinces. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mcloughlin, C. 2014. Political Economy Analysis: Topic Guide (2nd Edition). GSDRC, University of Birmingham.

Mcloughlin, C. and Batley, R. 2012. The effects of characteristics on accountability relationships in service delivery. Overseas Development Institute Working Paper 350. Retrieved from https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/7790.pdf

Mcloughlin, C., & Batley, R. 2013. The Effects of Sector Characteristics on Accountability Relationships in Service Delivery. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2209074

Menocal, A. R. (2015). Political settlements and the politics of inclusion. The Developmental Leadership Program State of the Art 7. Retrieved from https://res.cloudinary.com/dlprog/image/upload/VctJ5OgDnbepffnS0Wvy53j5YyXKxfvKUHfPevB8.pdf

Menocal, A.R, Cassidy, M., Swift. S., Jacobstein, D., Rothblum, C. and Tservil, I. 2018. Thinking and Working Politically Through Applied Political Economy Analysis: A guide for Practitioners. Center of Excellence on Democracy, Human Rights and Governance. USAID. Retrieved from https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/PEA2018.pdf

Menocal, A.R. 2017. Political settlements and the politics of transformation: where do ‘inclusive institutions come from? Journal of International Development 29, 559-575. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3284

Mitchell, D., & Mitchell, R. 2003. The Political Economy of Education Policy: The Case of Class Size Reduction. Peabody Journal of Education, 78(4), 120-152. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/1492959

Moore, M. 2015. Creating efficient, effective, and just educational systems through multi-sector strategies of reform. Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) Working Paper 15/004. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-WP_2015/004

Nicolai, S., Wild, L., Wales, J., Hine, S. and Engel, J. 2014. Unbalanced progress: What political dynamics mean for education access and quality. Overseas Development Institute Development Progress Working Paper 05. Retrieved from https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/9070.pdf

Oliver, K., and Faul, M. V. 2018. Networks and network analysis in evidence, policy and practice. Evidence and Policy, 14(3), 369–379. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426418X15314037224597

Paglayan, A. S. 2017. Civil War, State Consolidation, and Mass Education. Retrieved from https://www.riseprogramme.org/sites/www.riseprogramme.org/files/inline-files/Paglayan%203.pdf

Paglayan, A. S. 2018. Democracy and Educational Expansion: Evidence From 200 Years. (Dcotoral Thesis). Center for Global Development. Retrieved from https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/a763a0_7c8de837bc4f452bb8935b8266c01975.pdf

Parks, T. and Cole, W. 2010. Political Settlements: Implications for International Development Policy and Practice. The Asia Foundation Occasional Working Paper 02. Retrieved from https://asiafoundation.org/resources/pdfs/PoliticalSettlementsFINAL.pdf

Perry, K.K. 2015. Political settlements, state capacity and technological change: a theoretical framework (Doctoral Thesis). Globelics Academic 2015, University of Tampere, Finland. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/74f6/5569a49ad9679ecb6a54bc9395264b521d44.pdf

Poole, A. 2011. How-to Notes: Political Economy Assessments at Sector and Project Levels. World Bank. Retrieved from http://www.gsdrc.org/docs/open/pe1.pdf

Pritchett, L. 2018. The Politics of Learning: Directions for Research. Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) Working Paper 18/020. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-WP_2018/020

Pritchett, L. 2019. Understanding the politics of the learning crisis: steps ahead on a long road. In Hickey, S., Hossain, N. (2018). The Politics of Education in Developing Countries – From Schooling to Learning? (197-209) Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rodrik, D. 2014. When Ideas Trump Interests: Preferences, Worldviews, and Policy Innovations. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28 (1), 189-208. doi: https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.28.1.189

Rosser, A. (2018). Beyond access: Making Indonesia’s education system work. Lowy Institute. Retrived from https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/beyond-access-making-indonesia-s-education-system-work

Rosser, R., Wilson, I. & Sulistiyanto, P. (2011). Leaders, Elites and Coalitions: The Politics of Free Public Services in Indonesia. Developmental Leadership Program Research Paper 16. Retrieved from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Leaders%2C-elites-and-coalitions%3A-The-politics-of-in-Rosser-Wilson/b2faa4e6eeaae75257eaacfa587a3d0946c36dc1

Sandholtz, W. A., Romero, M., & Sandefur, J. (2018). Electoral incentives for public good provision: Evidence from three linked field experiments in Liberia. American Economic Review – forthcoming.

Savage, L. 2013. Understanding ownership in the Malawi education sector: ‘should we tell them what to do or let them make the wrong decision? (Doctoral thesis). University of Cambridge.

Schiefelbein, E. and McGinn, N. F. 2017. Learning to Educate. Learning to Educate. UNESCO/International Bureau of Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-947-8

Schneider, B.R., Estarellas, P.C. and Bruns, B. 2017. The Politics of Transforming Education in Ecuador: Confrontation and Continuity, 2006-17. Comparative Education Review, 63 (2), 259-280. https://doi.org/10.1086/702609

USAID. 2016. Political Economy Assessment – Field Guidance. USAID Applied Political Economy Analysis (PEA) Draft Working Document. Retrieved from https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2496/Applied%20PEA%20Field%20Guide%20and%20Framework%20Working%20Document%20041516.pdf

Watkins, S. and Ashforth, A. 2019. An Analysis of the Political Economy of Schooling in Rural Malawi: Interactions among Parents, Teachers, Students, Chiefs and Primary Education Advisors. 19/031. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-WP_2019/031

Williams, T. 2016. Oriented Towards Action: The Political Economy of Primary Education in Rwanda. Effective States and Inclusive Development (ESID) Working Paper No 64. Retrived from http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2835537

Wilson, R. W. 2005. Political culture and the persistence of inequality. East Asia, 22(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12140-005-0017-3

World Bank. 2007. Tools for Institutional, Political, and Social Analysis of Policy Reform – A Sourcebook for Development Practitioners. World Bank. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/6652

World Bank. 2008. The Political Economy of Policy Reform: Issues and Implications for Policy Dialogue and Development Operations. Social Development Department. World Bank. Retrieved from http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/571741468336058627/pdf/442880ESW0whit1Box0338899B01PUBLIC1.pdf

World Bank. 2010.The Political Economy of Reform: Moving from Analysis to Action. A Global Learning Event Summary Note. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/282321467995076666/The-political-economy-of-reform-moving-from-analysis-to-action-a-global-learning-event

World Bank. 2016. Making Politics Work for Development: Harnessing Transparency and Citizen Engagement. Policy Research Report. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0771-8

World Bank. 2016. The role of Political Economy Analysis in Development Policy Operations. Independent Evaluation Group. World Bank. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10986/25866

World Bank. 2018. World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education’s Promise. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1096-1

World Bank. What is Stakeholder Analysis? Retrieved from http://www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/anticorrupt/PoliticalEconomy/stakeholderanalysis.htm

Gershberg, A. 2021. Political Economy Research to Improve Systems of Education: Guiding Principles for the RISE Program’s PET-A Research Projects. 2021/030. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-RI_2021/030