Marla Spivack

World Bank

Other

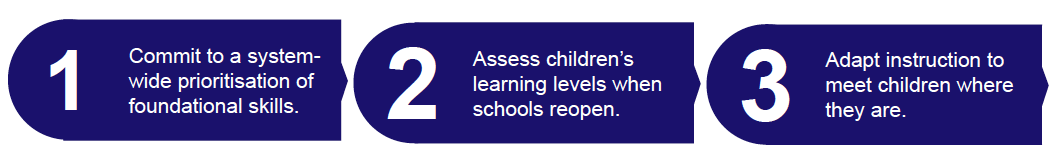

Education systems around the world were already facing a learning crisis before the COVID-19 pandemic. If nothing changes, school closures due to COVID-19 will exacerbate this learning crisis. But insights from recent research on education systems suggest that three steps can mitigate these losses and make systems better in the long run:1

Learning levels in many developing countries were already low before the COVID-19 crisis: 53 percent of children in low- and middle-income countries cannot read and understand a simple text by age 10 (World Bank). Over the last two decades, more children than ever have gained access to school, but overall learning levels among children in school have not kept pace and in many cases have fallen.

Several features of the learning crisis set the stage for COVID-19 school closures to severely impact long-term learning outcomes:

Projections and empirical estimates of learning losses over summer holidays and due to natural disasters suggest that these factors will combine to produce COVID-19 learning loss in two ways:

Education systems must prioritise helping children catch up so that the learning losses experienced now during the COVID closures do not undermine learning for years to come, impacting later life outcomes including earnings, health, and empowerment (Kaffenberger et al., 2020; Andrabi et al., 2020; Vegas et al., 2020).

Ensuring that children are safely able to return to school is vital (Carvalho et al., 2020). Once this is achieved, a system-wide commitment to prioritising foundational skills will be critical to ensuring that students get back on track after a long period away from school.

Foundational skills must be a priority. Even before COVID-19 school closures, the majority of children in developing countries did not master foundational literacy and numeracy (World Bank), which are critical to unlocking children’s ability to access more complex content (Belafi et al., 2020). Children who fail to master foundational skills are the most vulnerable to long-term learning deficits. They are likely to fall farther and farther behind when schools reopen if the curriculum continues to progress at a pre-crisis level and pace.

Political and educational leaders should affirm that foundational skills are a priority, and articulate clear, achievable goals to reinforce this commitment. Education systems perform best when delegation is clear and consistent. When the priorities are made clear, education’s various subsystems - curriculum, human resource, trainings, assessments and others - can more easily work together towards that goal, rather than advancing their own disparate approaches (Crouch, 2020). Similarly, clear delegation also allows frontline providers like school leaders and teachers to adapt to the challenges they face in ways that deliver on those priorities.

When children return to school, learning levels among children in the same class are likely to vary considerably and be lower than expected for their grade level. Students will have had differential levels of access to remote learning and parental support during time away from school (Andrabi et al., 2020; Crawfurd, 2020; Tiruneh, 2020). In order to get students back on track, teachers must know the learning levels of the students in their classrooms. Teachers will need resources to conduct diagnostic assessments and support, from within their school and from education authorities, to process this information and use it to adapt their classroom practice to children’s learning levels.

Education systems and teachers should prioritise using assessments to understand where children stand in foundational literacy and numeracy. The approach should take advantage of high-quality assessments already in use. For example, instruments used by citizen-led assessment organisations can be adapted for use in the classroom (PAL, 2020; Banerji, 2020a; Beatty et al., 2020; Verman, 2020). In cases where diagnostic tools are not available, an abbreviated version of summative assessments from the previous year could be adapted for this purpose (Beatty et al., 2020). Once an initial assessment has been conducted, it can be repeated periodically to help children consolidate their learning and to enable teachers to monitor progress, tailor instruction, and offer further remediation when needed (Hwa et al., forthcoming).

As schools reopen, teachers should focus on helping students progress in foundational literacy and numeracy rather than on moving through the standard curriculum, and progress should be measured in terms of student improvement from baseline rather than against a curriculum standard (Beatty et al., 2020).

To achieve this, teachers will need not only information on students’ learning levels, but also the authorisation, resources, and capability to align teaching to be coherent with students’ growth needs, and the support to put new practices into action. The approaches to adapting instruction can vary and should be aligned with the existing system. For example, school leaders could decide to devote an hour each day to review basic literacy and numeracy respectively (Banerji, 2020a), or existing toolkits and targeted instruction programmes can be adapted to be implemented in classroom settings (Beatty et al., 2020; Cilliers, 2020). Adequate resources, toolkits, and rapid training – some of which can be delivered remotely – should all be a part of the strategy. With clear goals and adequate support, teachers can be empowered to choose the practices that will work for their classroom.

Some of the COVID-19 pandemic’s farthest-reaching effects are likely to be felt in the later-life outcomes of today’s young children. Education systems have a critical role to play in mitigating these effects. By prioritising foundational skills, determining children’s needs when schools reopen, and adapting to meet children where they are, we can both blunt the worst effects of this crisis on learning and strengthen systems for the future. Planning for this brighter future must start now.

This brief was developed with input from the team of researchers at the RISE Directorate: Carmen Belafi, Yue-Yi Hwa, Michelle Kaffenberger, and Jason Silberstein. It draws on work from researchers across the RISE Programme.

Spivack, M. 2020. To mitigate the effects of COVID-19 on education outcomes, systems should prioritise foundational skills and adapt instruction to children’s learning levels. Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE). Issue Brief 20/01. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-IB_2020/01