Jacobus Cilliers

Georgetown University

Insight Note

The most pressing problem facing all education systems is how to provide remedial education to students once schools reopen. Children will return with a large learning deficit, with some more behind than others. Teachers will face the challenge of providing instruction over an even more academically diverse classroom than before. There is a real risk that the children who fall behind the curriculum might learn at a slower pace for the rest of their school career.

The good news is that there is a methodology that has been proven to be highly effective in many different contexts: targeted instruction, which tailors instruction to the learning level of the child. This insight note draws on evidence from multiple field experiments conducted in Ghana and India, and highlights some key principles that should be kept in mind when implementing targeted instruction, with specific reference to the Tanzanian context.

Targeted instruction typically has three components:

There are several modalities to consider, depending on who will implement the proposed strategy (teachers or volunteers), and when it should be done (school hours or after school hours). Based on the evidence, two effective modalities seem to be ones where:

Regardless of the modality, all implementers should remember the following core principles:

Develop an adapted curriculum which allows for providing tailored instruction. This could include additional learning exercises, lesson plans, and learning materials to support teachers in the enactment of the curriculum.

Provide high-level, ongoing, teacher professional development support.

As schools start to re-open, children will return with a large learning deficit: they will most likely know less than they did before the schools closed. In Malawi, authors found that children in early grades lost roughly a third of what they had learnt during the year, after the summer break.1, 2 And these learning deficits will not be equally shared: children of poorer and uneducated parents typically fall further behind when schools close, relative to children with more educated parents.3 But this is not the worst news: there is a real risk that children who fall behind the curriculum learn at a slower pace for the rest of their school career, so the learning loss will just compound over time.3

Teachers will therefore face two challenges: (i) helping children who are behind their curriculum, and (ii) teaching classrooms with remarkably diverse levels of learning and emotional needs. These challenges are not new. There is strong evidence that the mismatch between student ability and curriculum is one of the largest reasons why most children in developing countries are learning very little at school. But the school crisis will dramatically amplify this challenge, and governments will have fewer discretionary resources than before.

The good news is that there is a methodology that has been proven to be highly effective in many different contexts: targeted instruction, which tailors instruction to the learnings levels of the child. The bad news is that it takes a lot of planning and work to get it right. It requires developing an adapted curriculum, providing teacher professional development support, and undertaking ongoing monitoring to help teachers apply the method correctly.

Governments across the developing world have been experimenting with ways to provide targeted instruction: tailoring instruction to the learning levels of the child. Targeted instruction has three core components: (i) Student assessment, using a simple instrument, on an ongoing basis; (ii) grouping students by their ability; and (iii) the delivery of a curriculum (with specific learning activities and learning materials) that is appropriate for each group’s ability level.

There are multiple randomised evaluations that show the success of targeted instruction programmes. One set of evaluations documents a variety of experiences oriented to helping teachers teach students at their level of learning, called “Teaching at the Right Level” (TaRL) by the Indian NGO behind it, Pratham.4 Another successful example is a series of large field experiments on different ways to provide targeted instruction in Ghana.5, 6 Currently, targeted instruction is being implemented, in some form or another, all over the developing world including the following African countries: Botswana, Mozambique, Madagascar, Zambia, Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria, Ghana, and the Ivory Coast.7

This document discusses evidence from the field experiments conducted in India and Ghana.

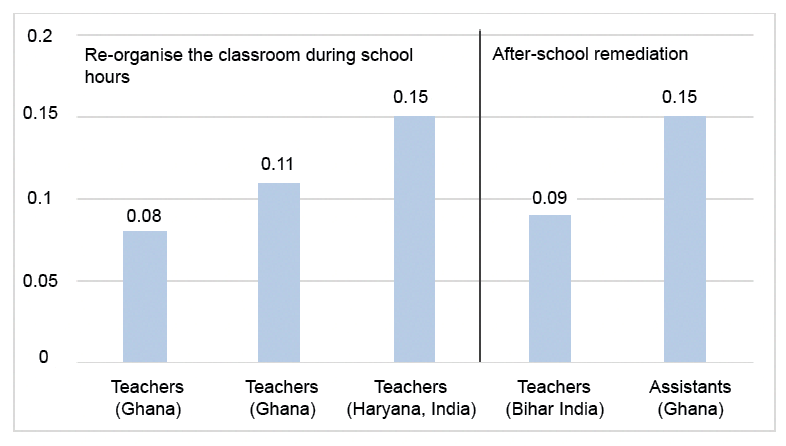

There are multiple ways to provide targeted instruction. The following three modalities have worked in multiple settings, with different degrees of success (see Figure 1 below):

Restructure the school day, so that children are grouped by ability and not grade for part of the school day. Teachers then deliver a curriculum which is appropriate to the ability level of the class.

This was implemented in both Ghana and Haryana state in India. In Ghana, teachers would combine Grades 1 to 3, and split these students by level of ability, for one hour each day.5 A different teacher would then focus on teaching children in each learning level. Children were assessed at the start of each term to determine their levels. This programme successfully improved student learning by 0.08 standard deviations in two years, and was as cost-effective as relying on assistants to teach outside of school hours. Based on the initial success, the Ghanaian government decided to scale up this programme, focusing on slightly older students in Grades 4 to 6. This programme was even more successful, improving student learning by 0.11 standard deviations in one year.6 The increased effectiveness was most likely due to improved monitoring.

Similarly, in Haryana state, the government mandated an extra hour of instruction in the school day. Teachers would merge and reorganise children in Grades 3 to 5 based on their ability. Children were assessed using a simple oral assessment at the start of the year to determine ability. The programme was fully supported and implemented by the government, and successfully improved reading ability by 0.15 SD.

Volunteer or Assistant teachers provide additional support to struggling children, during school hours.

Finally, volunteers can provide additional support to struggling children, during school hours. This was done in Ghana with paid assistants, applying the same methodology – assessment, grouping, and targeted instruction – as described above. Student learning improved by 0.15 standard deviations. Pratham also implemented variants of this model in Mumbai and Uttarkhand. In Mumbai, volunteers worked with students in Grades 3 to 4 who had not yet mastered the curriculum out of the classroom, and taught them for two hours a day.8 In Uttarakhand, volunteers supported teachers in their work within the school day. Neither of these two programmes were effective at improving student learning.

Remedial education programmes for struggling children, outside of school hours. This could be performed by either teachers or volunteers.

For example, a programme implemented by Pratham in Uttar Pradesh in India trained volunteers to teach children how to read using a simple pedagogy.9 These volunteers then held reading camps after school hours, lasting 2 to 3 months. Researchers found that children who attended camp sessions - and were unable to read anything before the programme - were 60 percentage points more likely to read because of the programme.

Similarly, in Ghana, assistants provided remedial instruction after school hours, for four hours a week.5 At the start of each term assistants tested students using a simple tool to determine who needed remedial instruction, and assigned them to one of three tiers of ability. Assistants would then deliver curriculum appropriate to their ability. The assistants worked on one level at a time (i.e., bringing Level 1 students up to Level 2, and then working with all Level 2 students, etc). Test scores improved by 0.15 standard deviations as a result of this intervention.

Another programme implemented by Pratham in Bihar province in India trained teachers to provide remedial lessons in summer camps. Student test scores improved by 0.07-0.09 standard deviations.

Note: Test scores improved by 0.11 standard deviations in Ghana6 and 0.15 standard deviations in India4 when teachers re-organised the classrooms and provided targeted instruction for one hour a day during school hours. Reported effect sizes are “intent-to-treat” estimates.

Regardless of the specific modality, there are some core features that all of the successful programmes share in terms of their implementation. These are critical for the success of the programme.

Curriculum: The existing curriculum can be adapted to provide specific guidelines for both the content and teaching practices, relevant for every ability grouping.

In both Ghana and India the curriculum had the following components; (i) simple and clear learning goals; (ii) examples of fun learning activities that should be used in the classroom; (iii) learning materials shared with teachers; and (iv) a scheme of work for the topics to be covered. Note that this curriculum should not replace the government curriculum, since the teaching guidelines can be aligned with the core learning competencies specified in the existing curriculum. In Ghana, there was a year-long process of mapping these core competencies to the targeted instruction curricula. Such a mapping process to ensure curricula alignment will sustain a targeted instructional programme , and also ensures that teachers have the correct incentives to enact the curriculum. Education systems across the world do not have a year to prepare for the current crisis. Nevertheless, steps can be taken to streamline the curriculum to prioritise crucial, foundational skills.

Teacher support: Teachers need a lot of support to implement targeted instruction well. The most successful teacher support programmes are targeted pedagogical programmes that provide four key tools: (i) lesson plans, (ii) learning aids to be used in the classroom, (iii) training, and (iv) a system for ongoing monitoring and support (ideally coaching).

This will be the one of the largest challenges facing governments. There is a real risk that the common cascade model of training-of-trainers will substantially dilute the quality of training received by teachers. However, the case studies discussed above provide cautious optimism that something can be done, provided that the trainers get sufficient time to practice the methodology themselves, and there is a system of ongoing monitoring of both the trainers and the teachers.

For example, in the Haryana province in India, Pratham trained cluster-level government officials, who are responsible for providing support to 12 to 15 schools. These cluster officials then practiced applying the methodology themselves in schools for 15 days, before training the teachers. The 15-day period served two purposes: (i) the cluster officials became better trainers, because they understood and mastered the approach; (ii) the cluster officials became more supportive of the approach, because they could see the learning that took place during those 15 days. As a result, they took greater steps in ensuring that schools implemented the methodology.

In Ghana, there was a core targeted instruction team at a national level who were responsible for designing the programme. This team trained 24 national trainers, who then conducted training of teachers, head teachers, and circuit supervisors in all of the districts. Refresher training was also conducted in the second and third terms.

More importantly, teachers need to be empowered to apply the targeted instruction methodology. Remediation will inevitably take away from teachers’ time to complete all the instruction that was intended to be completed. Teachers will only apply this methodology if they understand from all of their supervisors (e.g., head teachers, district education officers, school inspectors) that this is a priority.

Higher-level top-down support and monitoring, which involves all education stakeholders.

Schools will only apply the methodology if the government makes it a priority. And teachers will only persevere in teaching a new curriculum and improve their teaching if they are supported and regularly monitored. This insight is best understood when comparing the failed attempts to apply the TaRL methodology at scale in Bihar and Uttarakhand, with the eventually successful approach in Haryana. To quote verbatim, the authors argue4:

"...mainstreaming these fundamental changes in pedagogy into the regular school curriculum is difficult without careful top-down support and monitoring. In teacher-led programmes that ran during the school year in Bihar and Uttarakhand, classrooms were never re-organised around initial learning levels. By contrast, the teacher-led programme in Haryana, which was implemented in a dedicated time slot, and included supervision by government monitors, led to successful reorganisation of classrooms and therefore higher reading scores. In Uttarakhand, even volunteers were not able to implement the grouping methodology since they were used by teachers as assistants to carry out their regular activities."

Similarly, in Ghana, all levels of government were involved in the creation of the material, training, and supervision. For example, the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment designed the learning materials; the National Inspectorate Board was responsible for the development of the circuit supervisors’ and head teachers’ intervention materials; the National Teaching Council was responsible for the development of the training materials and training for teachers; and all the regional and district directors in the country were invited to an orientation meeting, so they were informed and supportive of the programme.6

In fact, implementers of the programme believe that intensive monitoring was key to the success. National-level officials visited all of the districts and many of the schools, and invited district directors to join them in the monitoring. Their involvement made it clear to these schools (and their district level officials) the importance that the national level officials put on this implementation. The circuit supervisors also visited the schools in their circuit on a regular basis

As a starting point, it is important to adapt the curriculum for targeted instruction, which includes the learning goals, learning exercises, and supporting learning materials for each level of ability. This need not replace the existing curriculum, since it can match the grade-specific core competencies which are already specified in the curriculum.

Second, the Government of Tanzania needs to consider different modalities for providing targeted instruction. Since it is unlikely that there will be resources to pay for volunteers to provide remedial camps, the second modality is most feasible: existing teachers provide targeted instruction during school hours, for at least one hour a day.

Third, the programme needs to be piloted in some schools to test the methodology, and adapted and improved if necessary.

Fourth, steps need to be taken to ensure buy-in and support from the School Quality Assurance Division and the Regional and District Education Officers (REO/DEO). For example, there could be an orientation session in each region, with attendance from all the DEOs, District School Quality Assurance Officers (SQAOs), and the REO from that region.

Fifth, there needs to be high-quality professional development support. One option could be training a national team of 52 trainers. Groups of two then each perform training in the 26 regions in the country, travelling from district to district. The head teacher, teachers, and Ward Education Officers would be required to participate in this training. It is important that the head teachers participate in training, because they are responsible for implementing the re-organising of the classes, and need to work very closely with the teachers implementing the curriculum.

Sixth, a robust system of monitoring needs to be put in place, implemented by many levels of government. The Ward Education Officers are responsible for monitoring schools and teachers on an ongoing basis to make sure that they are being implemented, but this can be supplemented by monitoring from the SQAOs and DEOs.

1 Slade, T. S., Piper, B., Kaunda, Z., King, S., & Ibrahim, H. 2017. Is ‘summer’ reading loss universal? Using ongoing literacy assessment in Malawi to estimate the loss from grade-transition breaks. Research in Comparative and International Education, 12(4), 461-485

2 Cooper, H., Nye, B., Charlton, K., Lindsay, J., & Greathouse, S. 1996. The effects of summer vacation on achievement test scores: A narrative and meta-analytic review. Review of educational research, 66(3), 227-268

3 Das. J., Daniels, B. and Andrabi, J. 2020. We Have to Protect the Kids. RISE Insight Series. 2020/016. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-RI_2020/016

4 Banerjee, Abhijit, Rukmini Banerji, James Berry, Esther Duflo, Harini Kannan, Shobhini Mukherji, Marc Shotland, and Michael Walton. 2016. Mainstreaming an effective intervention: Evidence from randomized evaluations of “Teaching at the Right Level” in India. No. w22746. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2016.

5 Duflo, A., Kiessel, J., & Lucas, A. 2020. External Validity: Four Models of Improving Student Achievement (No. w27298). National Bureau of Economic Research

6 Beg, Fitspatrick, Lucas, Tsinigo, and Atimore. 2020. “Strengthening Accountability to Reach All Students: Endline Report”. Available here: https://tinyurl.com/ybc9wcyj

7 https://www.teachingattherightlevel.org/tarl-in-action/

8 Banerjee, A.V., Banerji, R., Duflo, E., Glennerster, R., and S. Khemani. 2010. Pitfalls of Participatory Programs: Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation in Education in India. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2(1):1–30

9 Banerjee, A.V., Cole, S., Duflo, E., and L. Linden. 2007. Remedying Education: Evidence from Two Randomized Experiments in India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3):1235– 1264.

10 Alfaro, Evans, and Holland. 2015. “Extending the School Day in Latin America and the Carribean.” Policy Research Working Paper.

This Insight was written by Jacobus Cilliers (Georgetown University) with inputs from Adrienne Lucas (University of Delaware), Joyce Jumpah (IPA Ghana), Sarah Needler (IPA), Sarah Kabay (IPA), Lucia Carillo (Georgetown University), Michelle Kaffenberger (RISE); and targeted instruction from David Evans (CGD).

Cilliers, J. 2020. How to Support Students When Schools Reopen? RISE Insight Series. 2020/018. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-RI_2020/018