Salimah Samji

Harvard Kennedy School of Government

Insight Note

Funda Wande is an organisation founded in 2017 with the goal of ensuring all students in South Africa can read for meaning and calculate with confidence in their home language by the age of 10.1 It develops curricula, videos, and print materials to train teachers in the fundamentals of foundational learning.

Funda Wande has adopted a ‘learning by doing’ strategy that is similar to the Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) approach to solving complex problems. PDIA is a high-impact process of innovation that helps organisations develop the capability to solve complex problems while they are solving such problems. It is a step-by-step framework that helps break down problems into their root causes, identify entry points, search for possible solutions, take action, reflect upon what is learned, adapt, and then act again. Its dynamic process and tight feedback loops enable teams to find and fit solutions to the local context.2

PDIA is gaining traction in development circles amongst practitioners as well as funders. However, many do not fully understand all the components and how they work in concert to produce results in practice. Though the Funda Wande team did not intentionally deploy the PDIA approach in their work, many features of their journey reflect the principles of PDIA. This case study is an attempt to map Funda Wande’s learning journey to core PDIA principles and tools to help programme designers and implementers better understand its application in the education sector. It can also be used in the classroom to teach PDIA.

This case provides a narrative of the Funda Wande story with boxes illustrating how PDIA principles and tools like problem construction, deconstruction, entry point analysis, iteration, and building authorisation would have been applied in practice. The sources of this case include a literature review of education in South Africa, related research documents, and conversations with staff at Funda Wande. We are grateful to the staff of Funda Wande (Nic Spaull, Nangamso Mtsatse, Nwabisa Makaluza, Julia Maphutha, Permie Isaac), Allan Gray Foundation (Natasha Barker), and MSDF (Sean Bastable) for their generosity of sharing their time with us.

Nic Spaull, the founder of Funda Wande and an economist by training, had been conducting research on the quality of education in South Africa since 2011.3 In 2015, he joined a large research project at Stellenbosch University under the Programme to Support Pro-Poor Policy Development, a partnership between the South African Presidency and the European Union. The research project was focused on identifying binding constraints4 in education and looking at root causes of low educational outcomes5 in order to make a recommendation.

The most troubling finding of this project was the striking fact that 58 percent of children in South Africa were unable to read for meaning in any language by the end of Grade 4.6

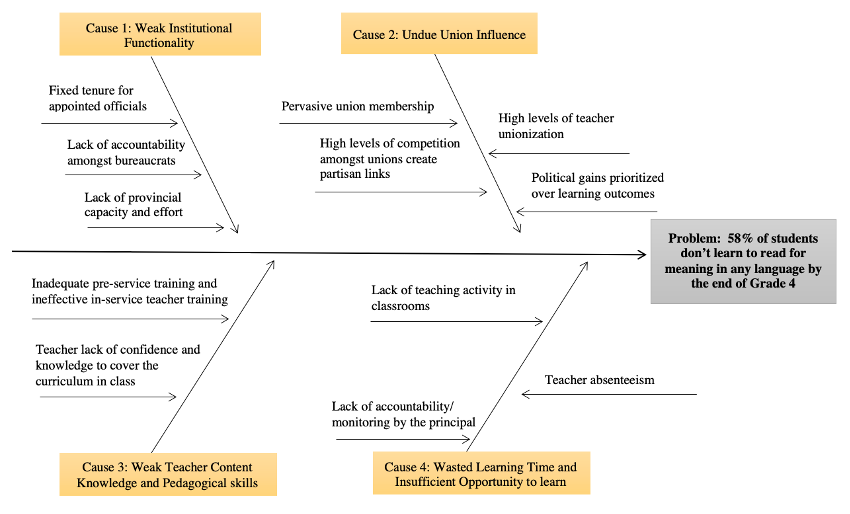

They identified four key binding constraints to progress on improving learning outcomes:7

Their synthesis report that identified these binding constraints included a strong recommendation that the Department of Basic Education adopt the objective that: “Every child must learn to read for meaning by the end of Grade 3.”

Boxes 1 and 2 on the following pages illustrate how the first two steps of PDIA, problem construction and deconstruction, can be mapped to the research findings above.

Problem construction is the first step in doing PDIA. It helps frame the problem and draw attention to the need for change in the social, political, and administrative agenda. In this example, the existing research on educational outcomes helped provide clarity, as well as a compelling narrative, around the problem of poor foundational skills.

Source: PDIA Toolkit Worksheet 1 using author’s synthesis of literature review and conversations.

Problem deconstruction is the second step in doing PDIA. Complex problems need to be broken down into smaller, more manageable sets of focal points for engagement that are open to localised solution

building. PDIA uses the Ishikawa or Fishbone diagram to illustrate this.

Below is our interpretation of Funda Wande’s initial Fishbone diagram based on the binding constraints to education research findings.

Source: PDIA Toolkit Worksheet 3 using author’s synthesis of literature review.

Spaull was already well known as an economist in the education sector, but the stark results of the binding constraints analysis increased his visibility and created the opportunity for him to rally a community of allies around the issue of foundational learning. It also led to many introductions to key stakeholders in the South African education system.

During one such meeting with the Allan Gray Foundation, where Spaull presented the binding constraints to foundational learning, something unexpected happened. The board of the foundation invited him to join them in putting his recommendations into action. Spaull’s first instinct was to decline. He wanted to focus on his research, and he had no team in place. But the Allan Gray Foundation was persistent. They thought he had a novel perspective on a persistent problem and believed that he had the potential to make meaningful progress on this issue. They promised to provide him with all the resources needed to continue his research while leading this new initiative at the foundation. Ultimately, Spaull agreed and Funda Wande was born.

Nic Spaull founded Funda Wande in 2017 with two trusted colleagues. During his previous work in the sector, he had observed that most researchers working in the education sector and particularly in literacy were neither native speakers of the local languages, nor had any experience of the public schooling system in deprived areas. He realised that he needed to build a competent and well-rounded team—one that had local contextual knowledge, understood the culture, and looked like the population he planned to work with.10

He began to bring together a representative and diverse group of motivated professionals who were excited about finding solutions to the problem of poor foundational skills. By the end of the year, they onboarded two black African women—Zaza Lubelwana (currently heading the pilot in the Eastern Cape province) and Nangamso Mtsatse (currently heading literacy and relationships). Over time, Spaull and the team leveraged their networks and brought on more native speakers of the local languages to join their core team. His approach to building his team has been intentional toward being inclusive, bringing more diverse voices to the table, and ensuring local contextual expertise.

Spaull’s hiring strategy was purposeful. He recruited, trained, and invested in people who were committed to staying within the broader education ecosystem. He also ensured that leadership and decision making was distributed.

Working in collaborative teams is an essential part of doing PDIA. Solving complex problems cannot be done by individuals. It requires involving different stakeholders who may not usually work together as they bring different perspectives and tacit knowledge that allows for a more robust understanding of the problem and generating ideas to act upon.

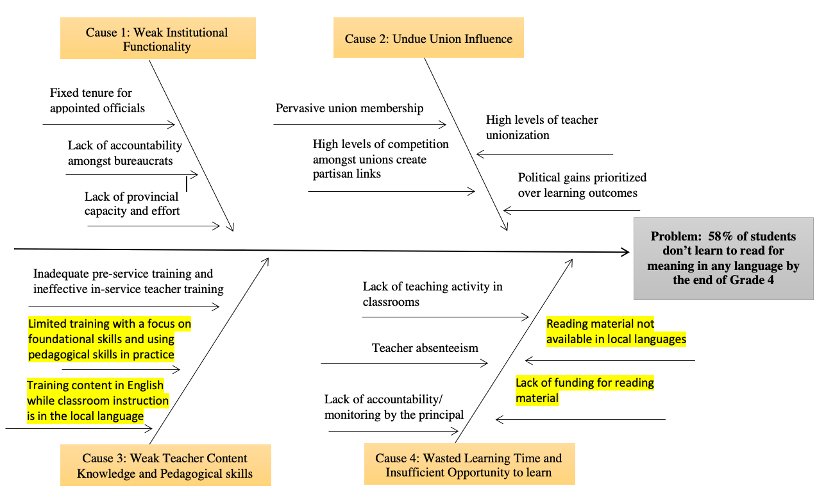

Funda Wande had set an ambitious goal: all South African children should be able to read for meaning by the end of Grade 3 by 2030. It knew that the key to success would have to include training teachers and equipping them with the tools to teach their students to read for meaning. However, before attempting to design any intervention, the leadership team spoke to pedagogical experts, universities, teachers, researchers, and government officials to get their perspective on the root causes of poor teaching skills and to brainstorm various ways to build this capacity. Through these conversations, they were able to gain key insights into the issues on the ground. First, there was a stark difference in the quality of teachers, quantum of funding, and quality of reading material across schools in different neighbourhoods. South Africa’s widening fiscal deficit and cuts in the education budget were further contributing to the inequality amongst schools. Second, quality learning materials in local languages were missing from schools. Children did not have access to appropriate print material needed for building a strong foundation. Third, there was no specific pre-service training course for teachers on foundational skills. Teachers simply did not have a meaningful learning opportunity to acquire this essential skill. Across the board, training content was in English—while classroom instruction was often in the local language. Additionally, in-service training courses did not emphasise practical knowledge of pedagogical skills. Many teachers highlighted that the 1-2-day training sessions were insufficient for them to retain and practice pedagogical skills in order to successfully use them in classroom.

Speaking to a broad range of stakeholders internal to the context is very valuable in refining the root causes of the problem. This process also helps build consensus on what needs to be prioritised and to gain legitimacy. The fishbone diagram is a dynamic tool and should be reviewed/updated regularly.

Below is our interpretation of Funda Wande’s updated Fishbone diagram after discussions with various stakeholders. New sub-causes are highlighted in yellow.

Funda Wande continued engaging with stakeholders for the next one and a half years to ascertain what was feasible for a new organisation entering the education ecosystem. Many questions still needed to be answered:

During this stage of exploration, Funda Wande realised that, in spite of the disproportionate attention that small scale efforts by NGOs and philanthropies get, the government spends ninety-nine times more money on education every year than all local and international philanthropies working in the country combined. This made it realise that it would be foolish to circumvent the government. Instead, its time and donor funding would be best spent influencing how the government could better spend its education budget. This early realisation helped Funda Wande focus on establishing partnerships with the government and not spreading itself too thin by trying to do everything alone. It knew engaging with the bureaucracy at the district, province, and national level would be critical for its success.

The stakeholder engagement prior to the design of the intervention helped Funda Wande identify opportunities to act and key agents who could take its mandate forward. Two entry points were selected: (i) Limited training with a focus on foundational skills and using pedagogical skills in practice, and (ii) reading materials not available in local languages.

These are two sub-causes in the fishbone diagram in Box 3.

The ideas to address these sub-causes included: (i) A practical teacher training course on foundational skills, and (ii) low-cost high-quality learning materials in the local language. Piloting and evaluating these interventions in schools would determine their effectiveness. Funda Wande decided to pilot the intervention in provinces that had low literacy levels. This would hopefully attract the attention of the other provinces and help get their buy-in. The two low-performing provinces at the time were Eastern Cape and Limpopo. It was able to gauge more support and excitement from the former and hence decided to begin the pilot in the Eastern Cape. Box 4 illustrates how entry points are identified in the PDIA process.

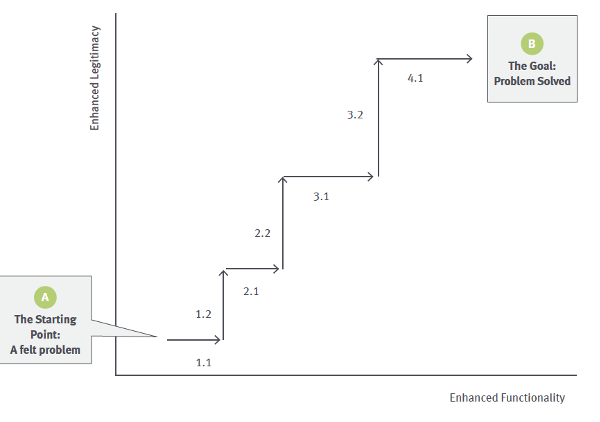

Sequencing is the third step in doing PDIA. Problem driven sequencing refers to the timing and staging of your engagement, given your contextual opportunities and constraints. Each cause and sub-cause of the fishbone diagram is essentially a separate point of engagement and offers different opportunities for change. This tool helps determine whether you should try an aggressive new policy intervention or start with something smaller and grow your change space first.

Below is our interpretation of Funda Wande’s change space analysis for one of the sub-causes highlighted in yellow on the fishbone in Box 3.

| Questions for Reflection | Estimate of: Authority, Acceptance, Ability (Low, Mid, Large) | Assumptions |

|---|---|---|

| Sub Cause: Reading material is not available in local languages | ||

| Overall, how much authority do you think you have to engage? | Large | Given the high acceptance of the issue in academia and funders, there will be support from these actors in addressing the problem. |

| Overall, how much acceptance do you think you have to engage? | Mid | Many provinces recognise the need for this however, creating quality materials is expensive and they have financial constraints. |

| Overall, how much ability do you think you have to engage? | Large | There is large ability amongst the academic and linguistic experts to create reading materials. |

| What is the change space for the sub-cause? | Medium change space | |

Source: PDIA Toolkit Worksheet 4 and author’s analysis.

The binding constraints in education research had identified the lack of pre-service and ineffective in-service training on foundational learning as a cause for poor foundational skills. Funda Wande began piloting a formal teacher training programme in partnership with the Rhodes University to ensure that all Foundation Phase teachers in the country knew how to teach reading to address this problem. The training course was prepared in isiXhosa (the local language spoken in the Eastern Cape) and English as a first additional language.

The team envisioned the in-service training being largely video-based to showcase the practical components in action, with on-site coaches visiting teachers in their classrooms once every two weeks. Funda Wande started filming professional in-classroom videos, creating animations, infographics, and other multimedia to teach the major components of reading and writing in practice. The in-classroom teaching videos were seen as a critical value addition to the training programme. The videos would show teachers how to use various teaching methodologies in live classrooms and serve as a guidebook post in-person training sessions. All the materials were tested by groups of teachers before finalising them.

“The two-day scoping trip was designed to give our team an important chance to prepare for our first wave of filming that’s coming up in October. Before diving into filming the real videos for the course, we wanted to “practice” a bit, and make sure of a number of key things: Would the scripts that our academic partners have been writing run smoothly? Would the teachers be camera shy? Would grade 3 learners be able to cope with the camera?”

- Blog entry by Funda Wande in 201811

This experimentation helped Funda Wande devise strategies to better fit the local context. It continued testing for about six months. A key insight from testing was that the videos didn’t mimic the environment of a target classroom because they were shot in a private school. Funda Wande knew that teachers would only find these videos valuable if they could identify with the context and see it working in a classroom that looked like theirs. Learning from this iteration, the final videos were recorded in public schools with a class size of 40-60 students and with school resources that most targeted teachers would have access to. Another piece of feedback from teachers was that they found it hard to remember all the training components and referring back to the videos would interrupt their workflow. This led to Funda Wande supplementing the videos with a written manual containing more visuals than text to serve as an easy reference for teachers in the classroom.

Funda Wande’s literacy work and training is largely led by native speakers of local languages in the organisation. They are the face of most videos and content uploaded on Funda Wande’s website and YouTube channel. This representation is highly appreciated by schoolteachers who trust and identify with those who are aware of their culture and context. Funda Wande distinguishes good teaching practices in targeted schools by featuring teachers on its YouTube channel. This creates recognition among teachers for their efforts and additional buy-in for Funda Wande’s teaching videos.

These training videos are a part of the pilot programme in 30 government schools in the Eastern Cape province. The intervention includes teacher training, learner and teacher support material and coaching for targeted schools. After finalising the design of the pilot programme, Funda Wande partnered with a local university to conduct a randomised controlled trial of the intervention to understand whether the pilot programme is achieving its goals. The pilot is currently ongoing and is expected to end in 2022.

Iteration is a key step in doing PDIA where multiple solution ideas are identified and put into action. Iterative steps progressively allow locally legitimate solutions to emerge and fosters adaptation to the idiosyncrasies of the local context. The initial steps are highly specified, with precise determination of what will be done, by whom, in relation to all chosen ideas, and predetermined start and endpoints that create time boundaries for the first step. Action learning is embedded in the iteration process. Check-in points help gather lessons to inform what happened and why, and next action steps are designed and undertaken based on what was learned in prior steps.

Funda Wande took six months to test what works and doesn’t work while developing the in-class training videos. The iterations provided immense learning about the location of the video recording, the person doing the training, and the creation of a supplemental manual to accompany the training videos. This learning helped it revise its strategies to better fit the context and to ultimately achieve its objective.

Source: PDIA Toolkit Section 6 and author’s analysis.

The Funda Wande team knew that public school systems, especially in the poorer provinces, faced financial constraints and lacked good quality textbooks in the local language. It felt that training teachers without quality learning materials would have a limited impact on learning outcomes as children need to practice their reading skills.

“Providing books and teaching teachers how to teach reading isn’t sexy, but neither is plumbing. Both are necessary for improvement – even in the ‘digital revolution space.’”

- Nic Spaull, 2019

Funda Wande saw that organisations like Room to Read (a non-profit) and Molteno (an institute of language and literacy) had created storybooks in isiXhosa but production was financially unviable due to the lengthy design of the books and the lack of economies of scale. Furthermore, they were not at par with private school textbooks and were visually unappealing. Funda Wande understood that only a cheaper set of materials would help them gain widespread readership. It collaborated with Molteno to redesign and repackage existing VulaBula reading materials into anthologies. By combining discrete story books into a single large book, they lowered the cost of printing significantly.

“One innovation was to convert the separate “skinny books” of graded readers into anthologies with 24 stories per book. By combining these texts into a single book, and because they are Creative Commons licensed materials, we can provide them at an extremely low cost. Once they are printed in large volumes the cost of a full-color anthology of 24 stories is about R15/book ($1/ book). Due to our collaboration with the Eastern Cape Department of Education (ECDOE), the province printed 824,345 isiXhosa and Sesotho anthologies for every Grade 1, 2, and 3 children in the province fully at their expense. These were distributed and used in 2019 and have again been printed and distributed for 2020.”

- Funda Wande Annual Report 201912

Today, all children attending R1 to R3 in public schools of Eastern and Western Cape provinces have a copy of these anthologies. The digital copy of these stories is also accessible (free of cost) to anyone on Funda Wande’s website.

“One of the ongoing mandates of Funda Wande is to find high-quality Open Access materials to use in our early literacy and early numeracy training. Where these do not exist, we create them.”

- Funda Wande Annual Report 2019

This fourth step of doing PDIA helps you look for and experiment with multiple alternative solutions. Solutions to complex problems come in the form of many small solutions to the many causal dimensions of the problem. They must be found within the changing context through active engagement and learning. Identifying multiple solutions whether through existing, latent, and external best practice or positive deviance yields positive and negative lessons and results in new hybrids or locally constructed solutions that are administratively and politically possible in the targeted context.

Funda Wande identified the need for creating textbooks in the local context. The existing content created by another organisation was appropriate but not administratively feasible due to the high cost of the printing. It improved the designs and helped bring down the cost of the textbooks. By collaborating with other organisations to support development of local language content, Funda Wande made learning materials, necessary for building strong foundational skills, accessible to every child.

Source: PDIA Toolkit Section 4 and author’s analysis.

Funda Wande understood that building administrative and political support for their interventions would be critical for the adoption in public schools. In the early days, it had a set of ideas that it wanted to pilot in partnership with the Eastern Cape province. Funda Wande created a compelling problem statement to capture the attention of government officials. It took several meetings and consistent engagement to get the government on board—but what sealed the deal was a series of high-quality anthologies of VulaBula stories it had created.

“During one of the initial meetings, we started handing over the Funda Wande anthologies. The officials were surprised by the quality of it, and all of them wanted it for their children. They know we are very serious about creating high-quality material at a low cost. We didn’t have enough copies to give it to everyone. We created this excitement in the room about what we are trying to do.”

– Nwabisa Makuluza, Funda Wande Head of Limpopo Province

The pilot in the Eastern Cape started off on a promising note but was nearly derailed a few months later as the top leadership of the Eastern Cape suddenly changed. Funda Wande was caught in the middle of this reshuffle as the incoming director had new priorities and was determined to cancel the programme. Funda Wande scrambled to meet the new director to convince him of the importance and potential of the programme. After a series of unsuccessful attempts, it finally secured a meeting with the new director. Funda Wande pitched its programme again, skilfully incorporating learnings from their previous engagement with the government. Other senior-level officials working in the Department of Basic Education also relayed the efforts of this collaboration and impact seen on the ground. Luckily the pitch worked: the new director was impressed by Funda Wande’s professionalism and the trust conveyed by other bureaucrats. The pilot was back on track.

“While working with the government, building buy-in at every level of the bureaucracy is critical to deal with sudden changes in the system. Patience and art of talking to the government are needed.”

- Nwabisa Makuluza, Funda Wande Head of Limpopo Province

On another occasion, the government suggested that the ongoing model of support offered by literacy coaches, one per five schools, was not a financially sustainable model that could be scaled up. Acting on this feedback, Funda Wande started exploring different models to continue maintaining the government’s interest and authorisation for the intervention. Funda Wande settled on leveraging the Presidentially-endorsed Youth Employment Service (YES) campaign to explore how youth can be productively employed in improving literacy and numeracy. Addressing the high youth unemployment rate (66 percent in 2019)13 is a top priority of the South African government, so this proposal to employ young people aligned with existing government priorities and was instantly popular. The administration quickly approved it.

The efforts to engage with the bureaucracy didn’t stop there. Funda Wande is encouraging Subject Advisors at the district level to enrol in the training programme on foundational learning offered by Rhodes University. Subject Advisors are responsible for designing training curriculums and providing pedagogical support to schoolteachers. Funda Wande sees building their capacity as a critical step in ensuring the programme’s sustainability going forward. It also persuaded the Eastern Cape Department of Education to offer bursaries to 21 foundation phase Subject Advisors to enrol in the programme.

Funda Wande is continuing to build a strong narrative around the problem through meetings and advocacy with officials at the province and national level, backed with evidence and solutions for making ‘read for meaning’ a priority countrywide. These continuous efforts have resulted in the inclusion of this topic in the Eastern Cape Department of Education’s Reading Plan14 as well as an acknowledgement by the President of South Africa.

“We agree on five fundamental goals for the next decade... (3) Our schools will have better educational outcomes and every 10-year-old will be able to read for meaning.”

- President Cyril Ramaphosa’s State of the Nation Address, 2019

This endorsement has created new opportunities for Funda Wande to collaborate with other provinces and has provided legitimacy to their mission.

In PDIA, trying small steps and learning to become more functional in your context allows you to gain more legitimacy to iterate again trying something bigger, learning again and gaining more legitimacy from the quick wins.

Source: PDIA Toolkit figure 5.

Besides targeting various levels of the bureaucracy, Funda Wande also values collaborating with other stakeholders (researchers, experts, NGOs, and future leaders) to advance the goal of every child being able to read for meaning.

Funda Wande organises a literacy conference, the Lekgotla Conference, in South Africa. This event gathers all the stakeholders working on literacy together. It provides funding for experts from other organisations, teachers, and district officials to attend the event and share their experiences. These conferences provide Funda Wande with an opportunity to revisit the root causes of poor foundational skills, build consensus on what needs to be done, share learnings, and find opportunities to collaborate.

Funda Wande is also promoting research on early foundational skills and local languages in South Africa by funding PhD bursaries for African home-language students at Stellenbosch University and sponsoring research on benchmarks in African languages and the analysis of PIRLS data. It is actively aligning research priorities with those of the Department of Basic Education to further improve the intervention design and content creation in local languages.

Building capabilities across the education system is an important way in which Funda Wande advances its own objectives. It believes in hiring and training people that are going to stay in the South Africa Education system. It realises that the problem cannot be solved by it alone or with the current capacity in the government. Thus, when recruiting it places an equal emphasis on required skills as well as future goals to be in the education ecosystem. Funda Wande invests time, effort, and money in preparing future leadership by helping them gain necessary experience and skills to do the job.

“Increasingly we see this as one of Funda Wande’s comparative advantages; giving promising young African scholars the opportunity to develop the skills and networks they need to succeed. This includes project management skills, developing relationships with key stakeholders, writing proposals, giving presentations, managing relationships with funders, delivering to a deadline, managing a team and a budget, and most importantly, learning how government processes and politics work in the real world. To do this we are supporting our staff to study part-time while they work at Funda Wande, as well as for deciding what opportunities and relationships people need to get to the next step in their career. Of our staff of 30 people, 10 are currently furthering their studies in some form or another with the majority paid for by Funda Wande.”

- Funda Wande Annual Report 2019

Iteration Authority to act on solutions is necessary for programmes and policies to work effectively. Programmes and policies typically cross over multiple authority domains in which many different agents and processes act to constrain or support behaviour. Authorising structures often vary vertically as well, with agents at different levels of an organisation or intergovernmental structure enjoying control over different dimensions of the same process. Authority is dynamic and with well-structured strategies, it can be influential in expanding change space.

Funda Wande engages multiple agents across the sector and organisations to ensure that reforms are viable, legitimate, and relevant. Building, maintaining, and expanding authorisations amongst various stakeholders has cultivated trust and a safe space for iteration and learning.

| Advocacy and relationship building within the government system | Providing platform and resources to external agents to advance existing capabilities | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| National | Advocating for reading for meaning; recognised as a national priority in 2019 | Researchers | Promoting research on early foundational skills by facilitating publications and sponsoring research |

| Province | Partnering to create educational plans for next 5 year, encouraging concerned government officials in the education department to enrol in the course for foundational learning. | Experts | Sponsoring to attend Literacy Lekgotla Conference hosted by Funda Wande to share learnings and resources |

| Districts | Encouraging and financially supporting subject experts to partake in course for foundational learning. | Future Leaders | Supporting staff internally to study part time, build skills and knowledge for next step in their career as future leaders |

| Schools | Training teachers followed by regular coaching support | Future Teachers | Providing accredited university course focused on foundational learning at the local universities |

Source: PDIA Toolkit Section 5 and author’s analysis.

“Everything we do is about prioritising and thinking whether this will lead to all children learning to read for meaning and calculate with confidence by age 10 by 2030”

- Funda Wande Annual Report, 2019

Funda Wande continues to tenaciously pursue its vision to transform basic education in South Africa. It continues to develop content in other African languages and build partnerships with other provinces. After seeing the effectiveness of the pilot programme, Eastern Cape government officials came back to Funda Wande with a request to include a numeracy programme, which it has called Bala Wande. Building on the learnings from its existing literacy programme, it has collaborated with other organisations to create cost-effective videos and learning materials.15

It is currently running interventions to improve early grade reading and mathematics in 30 schools in the Eastern Cape, 80 schools in Limpopo, and 50 schools in Western Cape. These interventions relate to using a combination of workbooks and teacher guides with different types of support: specialist teacher-coaches in Eastern Cape; teacher assistants in Limpopo; and subject advisors in Western Cape. Spaull left Funda Wande after five years. His replacement, Nangamso Mtsatse, was named as CEO in July 2021.16

Funda Wande’s iterative, learning focused approach allowed it to gain rapid traction on a long-standing problem.17 In just a few years, it has managed to create and maintain space for action within the government education system, and to design and implement solutions innovatively leveraging the capabilities that exist in the South African education sector. Education practitioners around the world can look forward to learning many more lessons and insights from their example.

Samji, S. and Kapoor, M. 2022. Funda Wande through the lens of PDIA: Showcasing a flexible and iterative learning approach to improving educational outcomes. RISE Insight 2022/036. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-RI_2022/036