Maryam Akmal

Center for Global Development

Blog

When Pratham used simple “report cards” to provide information about learning outcomes to villages in India, the intervention largely failed. There was no improvement in attendance of children or teachers, no improvement in learning outcomes; and parents, teachers, and village education committees did not become more engaged with the schools (Banerjee et al., 2010). However, when Pratham-trained youth volunteers offered basic reading classes outside of regular school, reading skills of children who attended improved substantially after one year.

Why did information provision fail to improve learning outcomes? Principals and teachers in these schools were both formally and informally accountable only via top-down reporting to the bureaucracies they worked for. Providing information to parents did not change their ability to hold the government schools accountable for results and hence could do little to improve outcomes. This is an example of incoherence between “client power” (parents to schools) and “management” (ministry to schools) in the RISE 4x4 framework of diagnostic for systems of basic education. The information via the community effort intended to strengthen the “client power” accountability relationship but it was incoherent with the information that the education bureaucracy in the “management” relationship collected and used for decision-making.

The role of information on learning to help improve education systems was a significant theme at the recent RISE Conference hosted at CGD.

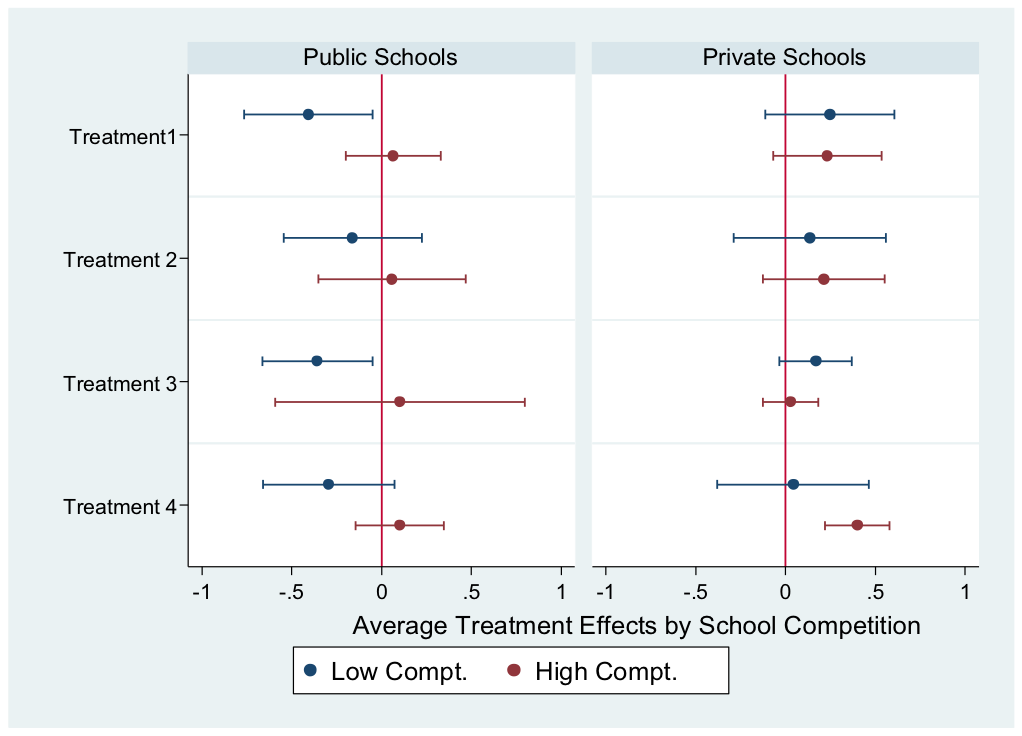

Farzana Afridi kick-started the second day of the conference by presenting her findings from a study (with Bidisha Barooah and Rohini Somanathan) where information on performance was provided to households and/or schools in Ajmer, Rajasthan in India. The study had four different “treatments” (based on what kind of information was given) and the results are separated into “high” and “low” competition areas. While there was no improvement in test scores of public schools in any treatments, there was significant improvement in test scores of private school students when both parents and schools knew relative school quality—especially when there was already high competition and lots of available choices for parents.

The figure below shows that providing information led to large learning gains when information on relative school performance was provided to both parents and students, and when competition was high. These are of course exactly the conditions that simple theory of choice would suggest—people will change their child’s school to seek higher performance when provided information that makes the choice across schools salient and the choices are otherwise close substitutes.

Source: Afridi, F., Barooah, B., & Somanathan, R., (2017), as presented at RISE Conference 2017

Note:

Treatment 1: Parents receive information on intra-school performance

Treatment 2: Both parents and schools receive information on intra-school performance

Treatment 3: Schools receive information on intra- and inter-school performance and parents receive information on intra-school performance only

Treatment 4: Both parents and schools receive information on intra- and inter-school performance.

In contrast, none of the information “treatments” had a positive impact on learning in public schools—in fact, in low competition environments all four treatments appeared to lead to lower learning. This is consistent with early results that changing only one aspect of a relationship of accountability (information) without changing others (e.g., the motivation of the providers) is unlikely to succeed—particularly when there are other incoherent accountability relationships at work (e.g., teachers reporting to a bureaucracy).

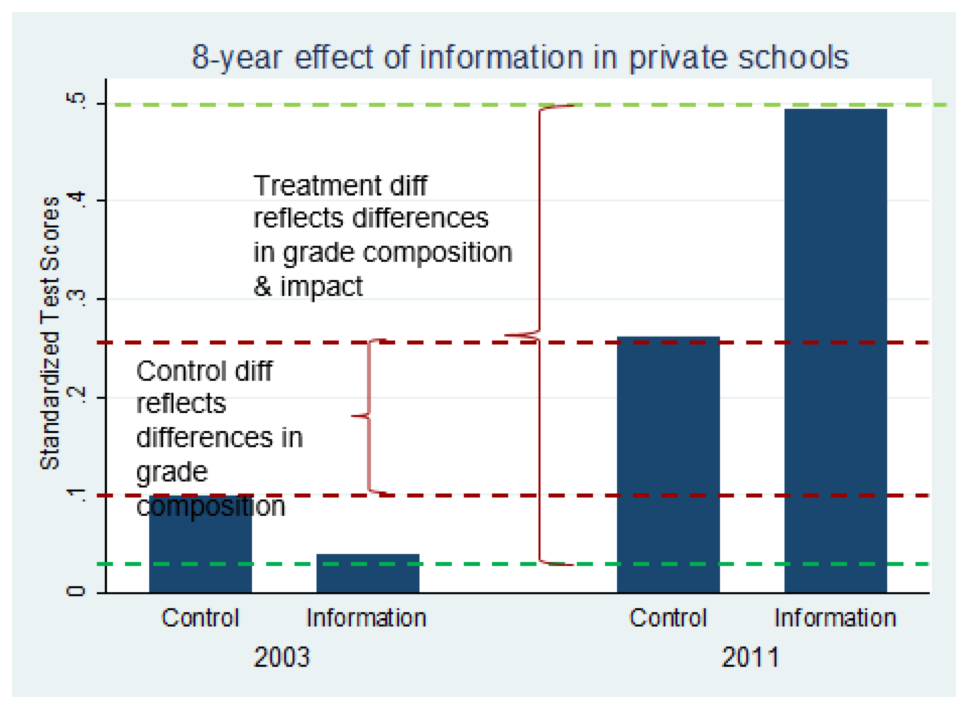

In another conference session, Jishnu Das presented new results building on previous work with Asim Khwaja and Tahir Andrabi where providing information on performance improved test scores and decreased private school fees in Pakistan. What is particularly noteworthy is that the effects were sustained over a long period of time at relatively low cost.

Source: Das, J., (2017), as presented at RISE Conference 2017

Looking back eight years later, the intervention: cost $2 per child, led to a $5.5 reduction in private school fees, and improved test scores for both private and public school students by 0.35 standard deviations and 0.12 standard deviation respectively. What we have here is a low-cost intervention with large, sustained results.

While all three studies mentioned study the impact of information provision on education outcomes, there are design differences across them. Banerjee et al. (2010) focused on public schools while Andrabi et al. (2016) and Afridi et al. (2017) focused on both public and private schools. Unlike Banerjee et al. (2010), Andrabi et al. (2016) and Afridi et al. (2017) provided information to both sides of the market, parents and schools. The results across the three studies varied as well. Banerjee et al. (2010) found no effect, the most recent results presented by Jishnu Das at the RISE Conference 2017 found that test scores increased by 0.35 standard deviations and 0.12 standard deviations for private and public school students respectively, and Afridi et al. (2017) found that test scores of private school students increased by 0.31 standard deviations with no impact on scores of public school students.

As always, design matters. Within Afridi et al.’s experiment, different treatment arms saw varying results. The improvements in test scores are highest when both parents and schools receive information about performance both within and across schools. The results seem to be mostly driven by high competition, as parents seem to move kids to better quality private schools. Giving report cards alone to schools didn’t make a big difference.

The answer is “it depends”—but the evidence appears to support common sense ways in which information provision “depends.” In a market-like environment where parents have lots of options, can vote with their money, and are receiving noisy signals of school performance, information matters. However, when parents are provided information but are constrained in their ability to exercise power over schools or teachers, information is likely to be ineffective.

Furthermore, design matters for construct validity. Different choices about the design elements of a specific intervention can have wide ranging consequences on the effectiveness of programs (Pritchett, L., 2017). Granular information about the design of experiments is key for determining their effectiveness. Statements like “information interventions don’t work” or “information interventions on average have small impact” based on a smattering of different experiments are useless, at best.

There are two main lessons

First, information improves outcomes when it improves accountability, and that requires designs that consider the realities of current accountability, who has power and why, and coherence within the existing system—in many existing systems teachers need not be accountable to parents at all.

Second, experiments are wonderful, but to understand and apply findings, knowing the experimental design and some theory is key.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.