Lee Crawfurd

Center for Global Development

Blog

“Angela Duckworth’s new book Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance has been launched with great fanfare, reaching number two on the NY Times Nonfiction bestseller list. She recently gave a very polished and smooth book launch talk to a packed audience at the World Bank, and is working with World Bank colleagues on improving grit in classrooms in Macedonia.”

That’s David McKenzie in a great book review, considering what development economists can learn from this hot psychology research trend. Grit – the ability to keep going when things get tough and you aren’t successful straight away – can help explain all sorts of individual outcomes beyond tests of skill or ability. David notes amongst other things how U.S. - centric the research on grit is, and questions how large the effect of grit is even in this context.

So what do we know about the importance of grit in developing countries?

Fortunately, a separate team at the World Bank has recently been rolling out a series of surveys measuring psychological traits including grit alongside measures of skills, income, and other demographics. Data is currently available for 10 countries; Armenia, Bolivia, Colombia, Georgia, Ghana, Kenya, Laos, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, and Yunnan Province (China).

Here’s what I found from some very quick analysis.

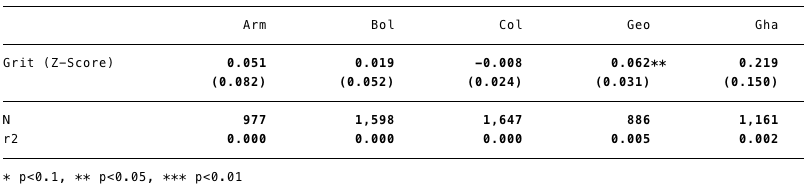

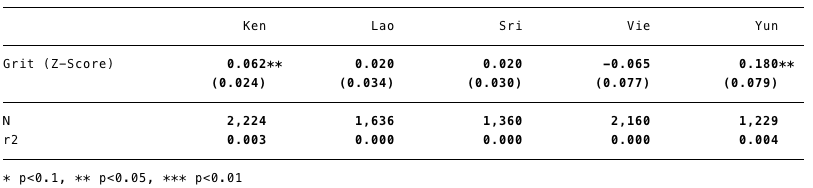

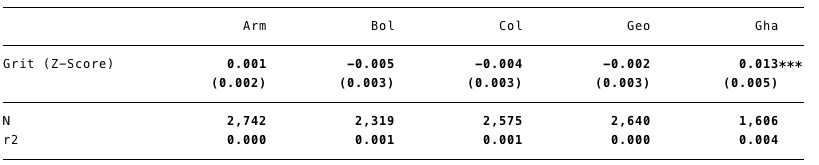

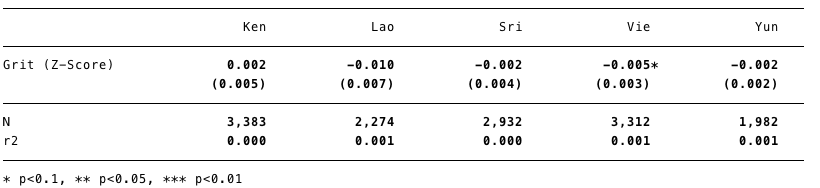

I started by looking at the relationship between adults’ grit and their earnings. For seven countries there is no relationship. For the three where some relationship exists, grit explains very little of the variation between the income of individuals. (That is, in the table below, the r2 statistic is less than 0.005.) Adding in a few basic control variables (age, parents’ education and socio-economic status) makes even that weak correlation disappear altogether.

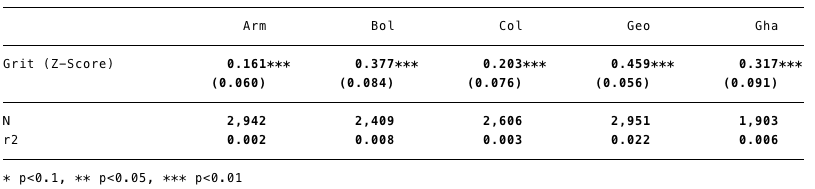

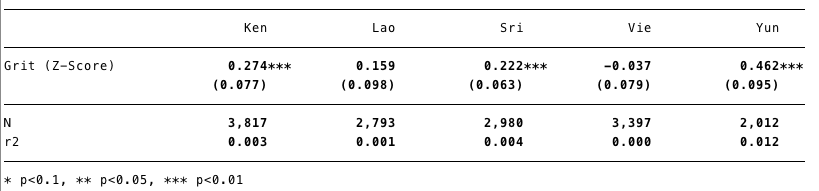

Moving next to years of schooling, something more substantial emerges. Grit has a statistically significant relationship with schooling in every country, and throwing in a bunch of control variables doesn’t seem to make it go away. I’m not sure what to make of the magnitude though - less than half a year of extra schooling for a 1-standard-deviation increase in grit. Maybe that’s a lot, maybe it isn't. I suppose the policy-relevant question is how responsive grit might be to interventions.

Finally, looking at the correlation with answers on a reading comprehension test. Grit scores pretty poorly here too; one positive correlation, one negative, and eight statistically insignificant. Other control variables by comparison do have the kind of statistically significant relationships you might expect - people tend to score better with more schooling and if they grew up in wealthier families.

I’ll spare you some of the snarkier comments from the office, needless to say that unsurprisingly to some, from a quick look the data does not seem to suggest that grit is all that important in explaining important outcomes in developing countries. Unsurprising, because all the grit and resilience and perseverance in the world is unlikely to help a child succeed at school if they haven’t eaten that day and their teacher hasn’t turned up due to a dysfunctional school system. Similiarly in the labour market, individual motivation and grit by itself isn’t going to create any well paying jobs in places where the demand for labour is low because of systemic factors such as bad infrastructure and bad governance.

I will offer one caveat – this measure of grit is based on only three questions rather than Duckworth’s preferred ten, so it is possible that a better measure of grit would matter more. But I doubt it.

And finally – this is not meant as a counsel of despair. For individuals living in low-income countries, of course they should try and persevere as hard as they can to try and achieve their goals. But when it comes to making policy – we should focus on the systemic constraints that are critical to shaping people’s opportunities, rather than just telling them to try harder. Bad schools, infrastructure, and governance, are all fixable public policy problems.

This blog was originally posted on the Roving Bandit website on 21 June 2016.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.