Lant Pritchett

Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

Blog

On 17 October, 2019, the World Bank announced a new goal and initiative to measure and eliminate education poverty. This is an exciting step in tackling the learning crisis. Their measure of education poverty focuses on a single, simple indicator: that every child should read fluently by Grade 4. Adding a goal that reflects a focus on Universal, Early, Procedural and Conceptual Mastery of Basic Skills (UEPCMBS), which is something that will have to be achieved if the broader SDG goals are to be achieved in any case, is potentially a good thing. Moreover, putting the achievement of learning for all squarely in the stream of “poverty” reduction, which acknowledges the multiple modes of human deprivation, again potentially adds drive, clarity, and motivation.

For this potential impetus to progress to be effective, there must be system-wide progress to achieve this goal, not just a few “education poverty” focused programs or projects. The need for system-wide focus is, in fact, the main lesson learned from the World Bank’s emphasis on and measurement of headcount income/consumption poverty.

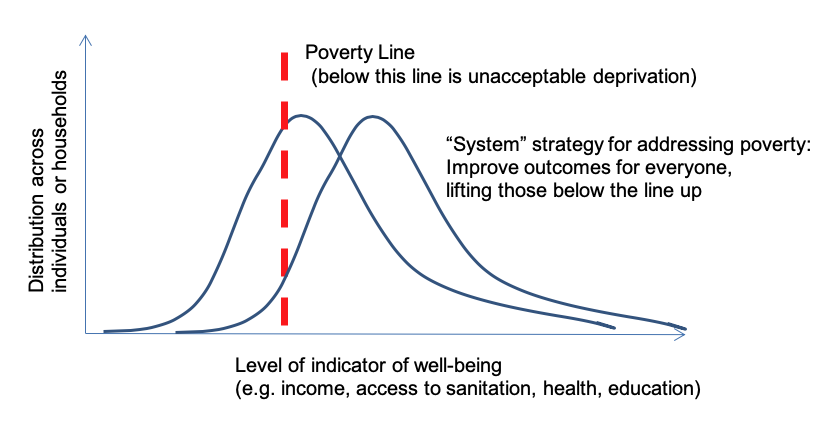

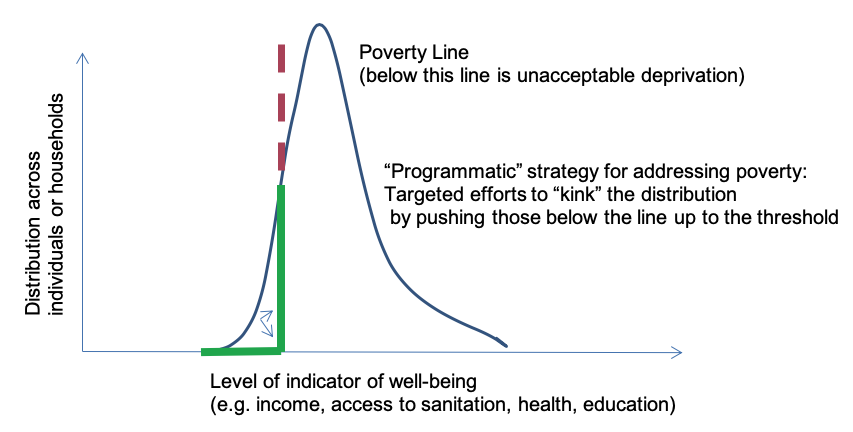

Pretty much every definition of “poverty” posits some element of human wellbeing (income, access to health care, water, nutrition, education) and a level below which there is “unacceptable deprivation” (which is ultimately a social decision). Given that poverty line, there are analytically two ways of reducing the number of people in poverty (in any dimension):

Figure 1a

Figure 1b

Castles in the sky are easy to build, and it is easy to imagine programs that are hugely cost-effective at achieving poverty targets. In the real world, however, it is an empirical question as to which of these strategies, system shift, or programmatic kink, is going to be more effective. This depends on what is contextually possible: politically, administratively, and technically.

Around the World Bank’s World Development Report 1990 that launched the measures of “dollar a day” poverty, there was a big debate about whether the strategy for reducing poverty was a “two-legged” stool (labor-intensive economic growth plus broad based investments in human capital) or a “three-legged” stool of those two plus “social protection” programs targeting the poor, and the compromise was a “two-and-a-half-legged stool”—which then led to laughter all around about how a good metaphor turned goofy: who wants a two-and-a-half-legged stool?

Of course, that debate about the relative importance of “growth” (or “shift” in the entire distribution of income) and social protection “programs” that aim to “kink” the distribution—and hence of poverty strategy—was a 2 plus a fraction 1/N approach, but what was N? Was N really 1, so it was really three-legged? Or was N really 100, so the poverty reduction stool was effectively two-legged? All of the debate in 1990 was carried out in the absence of any good time series data on poverty—necessarily so, as the “dollar a day” standard had just been invented for the report, and therefore we had only a cross-section to go on.

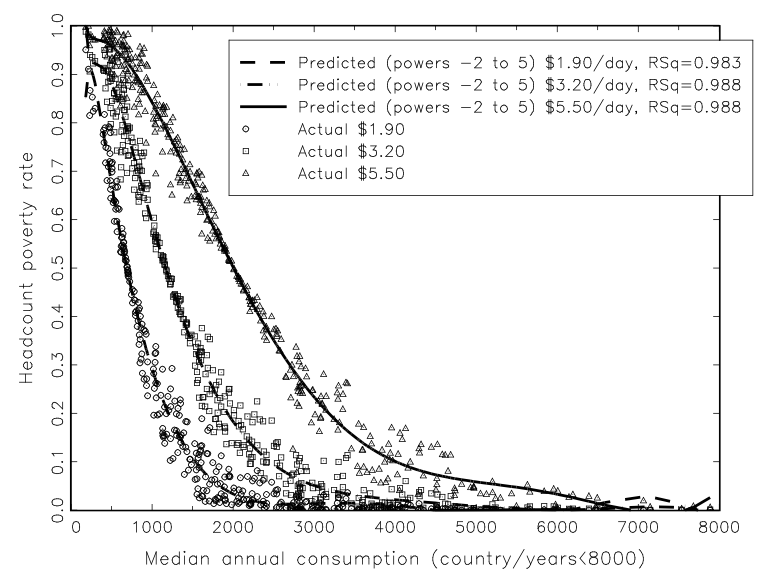

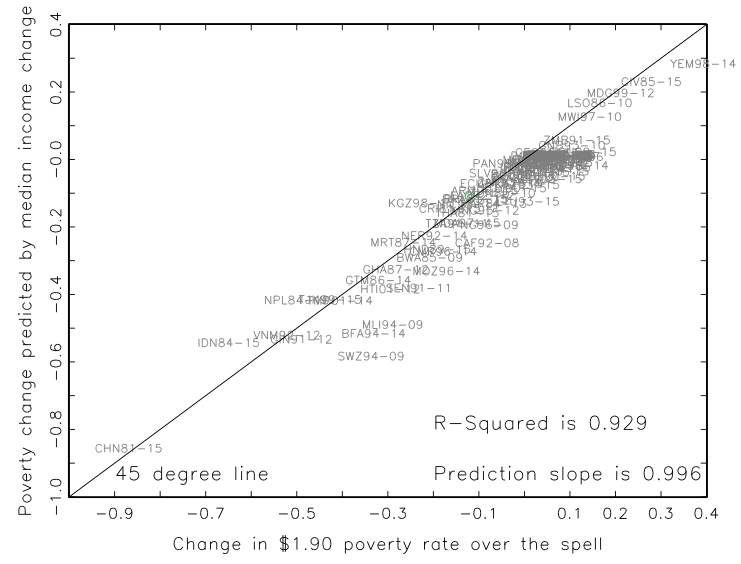

Now, 30 years later, we have good cross-section and time series data. The debate is over. Poverty reduction relies on growth in the overall distribution of income/consumption—and pretty much nothing else explains poverty across countries or over time. Figures 2a and 2b show that both in cross-section and over time the median of the distribution explains roughly all (an R2 of .98 in levels, .93 in changes, so both very near 1) of the variation across countries in headcount poverty. Improvements in the median consumption are an empirically necessary and sufficient condition for large scale poverty reduction.

This is not to deny that there might be cost-effective programs for addressing poverty, just that variations across countries in the scale and scope and effectiveness at which anti-poverty programs have been deployed to “kink” the bottom of the distribution up, do not appear to explain much (if any) of the differences in poverty across countries or over time. This is not an argument against poverty programs: they can be tactics. But the facts are a compelling obstacle to imagining that targeted poverty programs (those that reduce poverty without altering the median) can be, in and of themselves, an anti-poverty strategy (or even more than a small part of one).

Figure 2a and 2b: Poverty, in level and changes, is almost perfectly correlated with the level or change in median consumption

Figure 2a

Figure 2b

These lessons about poverty in general also apply to education poverty. Even if one adopts a clear target of eliminating education poverty, that does not imply that targeted programs are, or even can be, much of the solution. In a well-functioning education system, it might be that “inclusion” of the marginalized should be the primary strategy. But when the whole system is producing weak results for nearly every child, then “inclusion” is a false premise. In this situation, it is necessary to fix the whole system and increase performance across the board in order to reduce the number of children stranded in low performance.

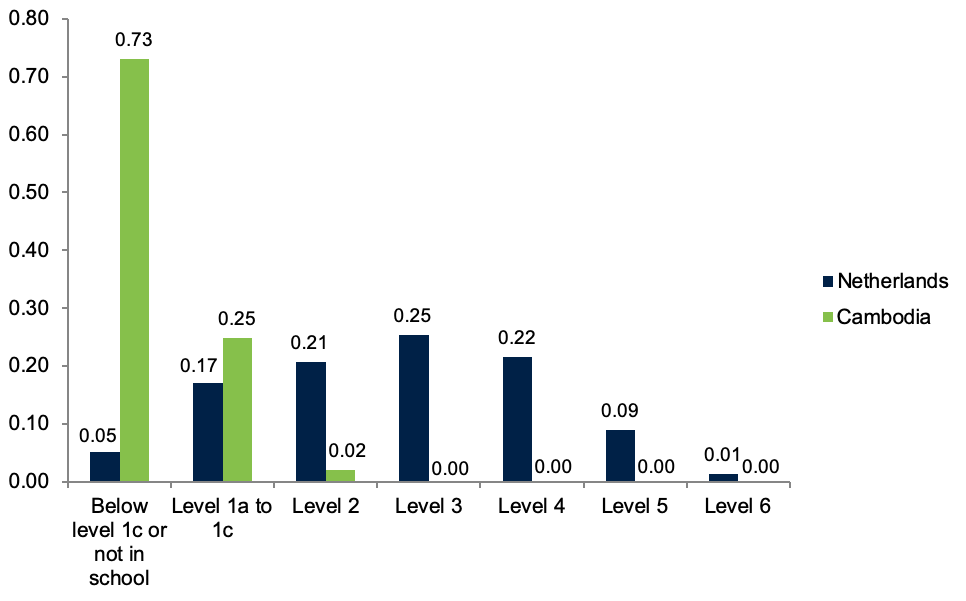

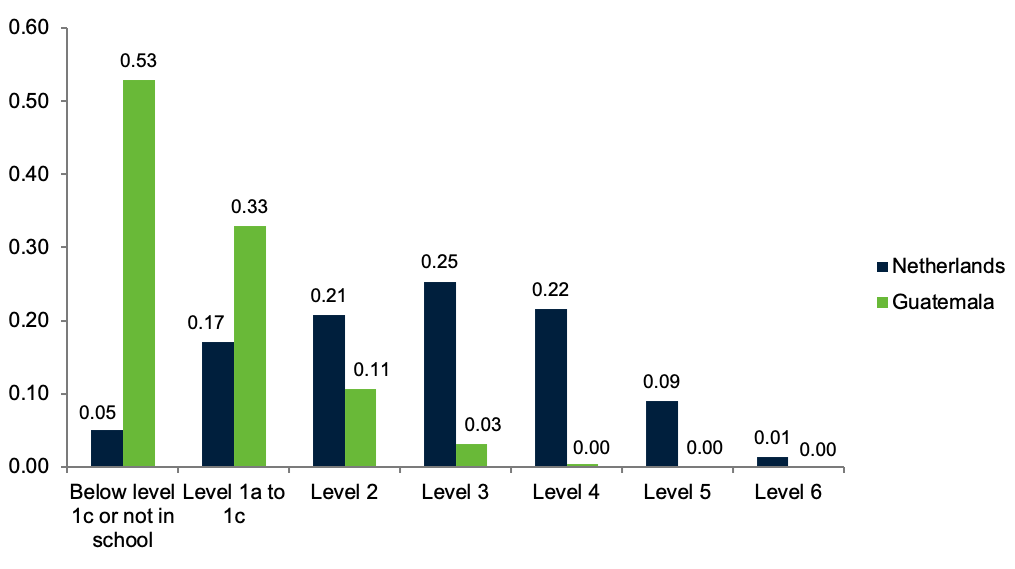

The recent PISA-D results illustrate that the problem isn’t that certain low income or socially excluded groups are getting a weak education; nearly everyone is. Figure 3a shows the distribution of results for 15-year-olds across PISA levels in Cambodia. About 2 percent were at PISA level 2 or above. Figure 3b shows the same distribution for Guatemala, which does better, but still only 14 percent are at level 2 or above.

Figure 3: Recent PISA results show that nearly all of the 15-year-old cohort in some low-income countries are below the “PISA level 2” learning threshold

3a: Netherlands and Cambodia

3b: Netherlands and Guatemala

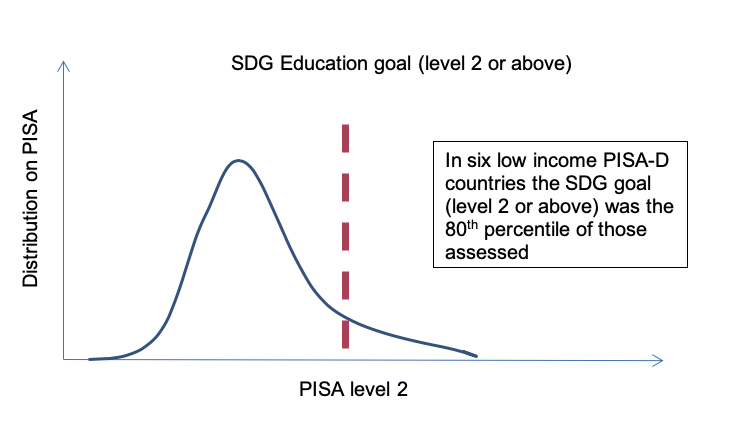

There is a powerful conceptual bias as “poverty” is often thought of as affecting only a small part of the population. This is the way Figure 1a is drawn, with the poverty line below the mode (and hence median and mean). This leads to an intuition that “targeting” can be a solution. But when global goals are posited, then “poverty” or “education poverty”—even at quite low levels—can actually be the vast majority of the population. In Figure 4 we show that “education poverty” (as the SDG target) is actually far above the mean/median. Pretty much the whole distribution of performance must shift upwards to make progress.

Figure 4: When low performance is the norm, system-wide improvement is the only feasible strategy

As Caine Rolleston and Luis Crouch (2017) have pointed out, the strategy of “raising the floor” is win-win for reforming weak systems. But this strategy is not a targeted program; rather, it is an approach to making the whole system coherent around reaching learning targets.

Attacking education poverty through the strategy of a “raise the floor” approach to “learning for all and all for learning” can be a powerful way forward for system reforms. The problem cannot be solved with only targeted programs and projects.

RISE blog posts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.