Ayesha Razzaque

Consultant

Blog

We examine teachers’ technology adoption behaviour in the context of a large-scale RCT-embedded pilot of a low-cost technology-enabled targeted instruction programme in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Technology uptake is not trivial, contrary to what some in Pakistani policy circles may believe. We have heard ministers excitedly talk about how they think technology can help ‘leapfrog’ and how it is the panacea to wide-scale educational problems. But think about the last time you shifted from one platform or technology to another and changed the way you routinely did things, no matter how small the shift was. Unless there is a big enough incentive or a major efficiency gain, most people remain reluctant to adopt new technology. This is even more true for populations that do not live or work in settings that are already digitised.

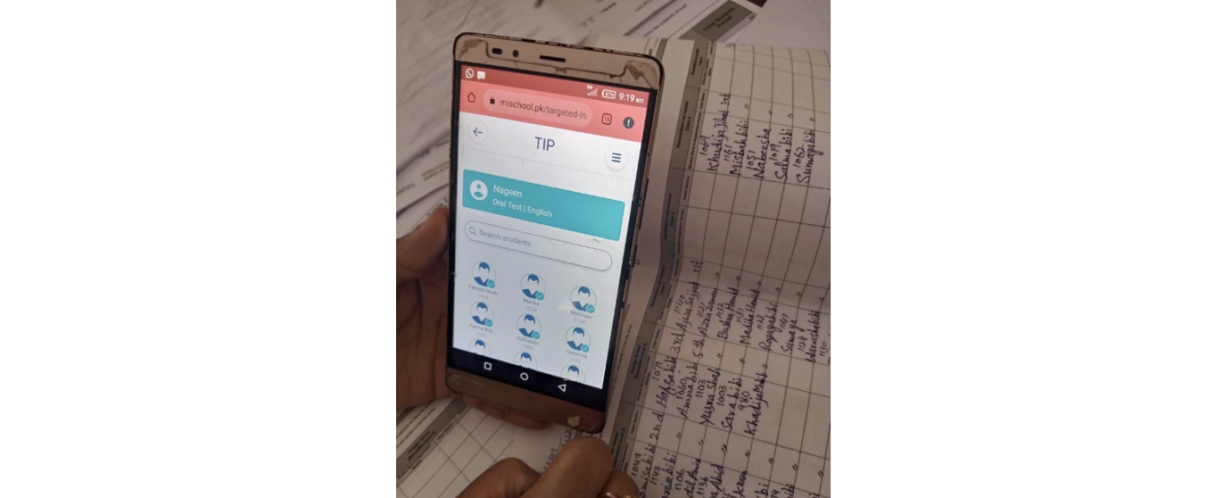

This blog post zooms in on an innovation—a teacher technology-support tool (referred to as the tech tool) and early insights into its uptake—that has been introduced in the Targeted Instruction in Pakistan (TIP) programme currently being piloted in 1,250 primary schools in the Mardan and Peshawar districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan and supported by the Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) programme. We will toggle between TIP and TIP-KP to refer to this programme for the rest of this blog post. Another version of this programme, supported by the EdTech Hub, is currently underway in over 500 public primary schools in the Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT).

Before proceeding further, a quick introduction of Targeted Instruction (TI) is warranted. However, note that this piece is not about the difficulties of adoption of the entire TI approach (whether tech-enabled or not) or features of the TIP tech tool or its (software) development process. What this blog post does focus on is some preliminary insights into ‘tech adoption behaviours’ of the primary beneficiaries of the TIP tech tool, i.e., the primary school teachers in TIP pilot schools.

We also want to acknowledge that there are massive literatures on teacher adoption of new teaching practices and rich literatures on people's adoption of technology generally. Our contribution through this blog post is related to this programme only.

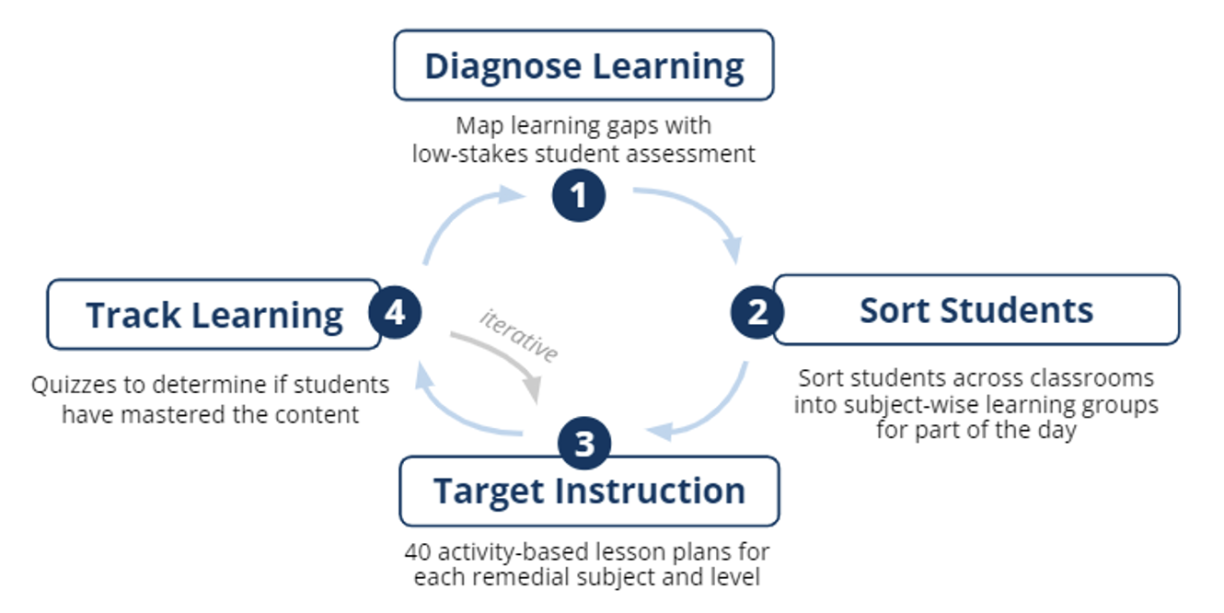

Around the world, Targeted Instruction interventions1 are systematic approaches to helping children catch up to grade level by filling in learning gaps in foundational skills. Rather than delivering standardised content to all students in a grade, a typical TI intervention assesses every student’s actual learning level and identifies the key concepts that are holding each child back. The programme then sorts students across or within classrooms into different groups according to learning levels, and teachers deliver targeted content that is most appropriate for each learning level. After the programme is completed, students return to their classes with the foundations they need to tackle more advanced content, allowing them to continue their learning journey through primary school and beyond. TI interventions can be conducted with or without technology. However, tech is particularly well suited to increasing efficiency in TI style programmes by facilitating the diagnostic and targeting processes.

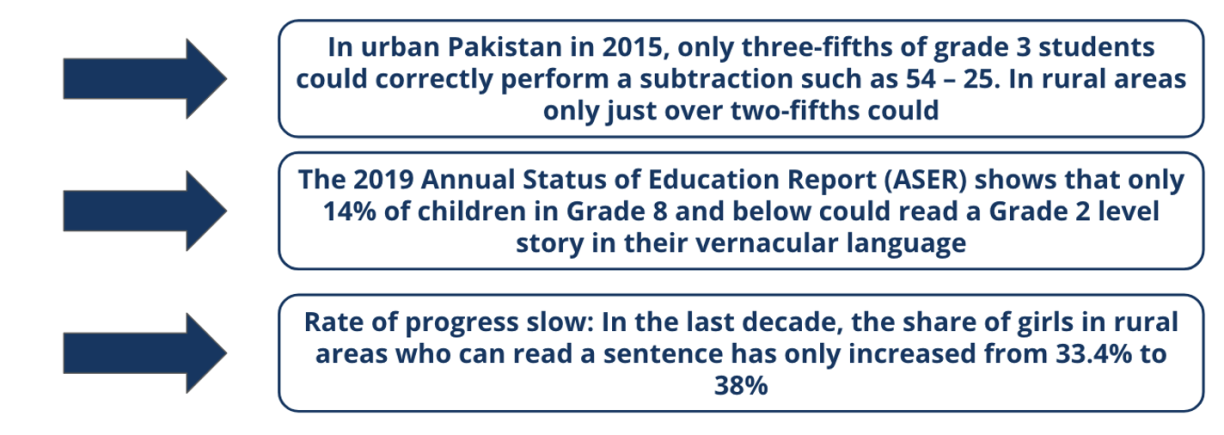

Data from domestic assessments2 tells us that primary school students are not learning at grade level, and COVID-induced closures have made matters worse.

There is growing recognition that children are not learning at grade level and that this has long-term ramifications. However, the public education system is not designed to address the learning issue at the risk of compounding learning losses as they build on shaky foundations. Focusing on ‘foundational learning’ is one solution to this perennial problem; and targeted instruction programmes are designed to address foundational learning gaps.

Overall, the TIP-KP model uses the basic composition described above; see Figure 2 below for a visualisation of the learning process that happens in TIP classrooms. However, what makes this programme unique is that it was designed with specific system-level frictions and constraints in mind and uses context-specific approaches to address these constraints, making it especially suited for deployment in Pakistan.

When we set out to design TIP, we knew that for a new intervention to work and scale efficiently it would have to address key constraints in the system at all levels. In our case this meant getting buy-in from:

To address the second constraint—i.e., to reduce administrative burden on teachers to make it easier to integrate innovative pedagogical practices with existing ones—TIP departs from traditional TI models in two unique ways:

While there is a plethora of learning management systems (LMSs) available for schools with many similar features, the TIP tech tool has been co-designed by local education experts and engineers with regular input from schools and teachers, specifically for use in low-resourced, low-digital literacy settings, such as public and low-cost private schools in Pakistan.

The TIP tech tool serves two main purposes (see Figure 3):

To understand how to address teaching and learning challenges, we describe three profiles of typical prospective TIP teachers included in the TIP pilot sample. We focused on providing a tech solution that addresses the needs of a large majority of teachers, although we realise that wide variation in levels of connectivity across school communities means it is not possible to develop a one-size-fits-all solution. While all these examples are from teachers in KP, we find that teachers in the Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT) have similar profiles and challenges.

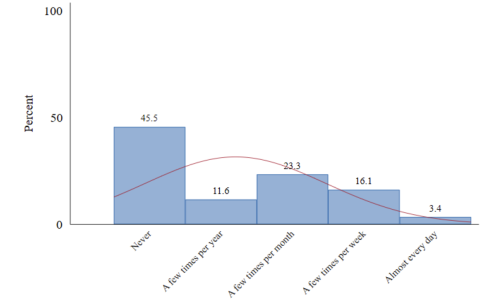

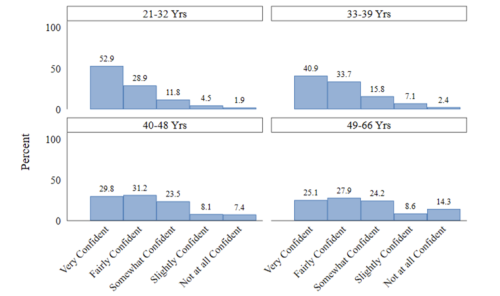

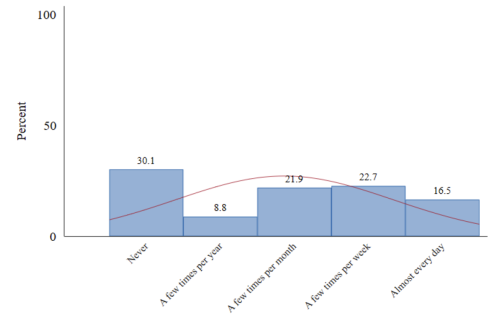

‘Arifa’ (pseudonym) is a primary school teacher at a girl’s school in urban Peshawar, with a master’s degree in education. Like 70 percent of teachers in the TIP sample she has her own smartphone and some technology skills. For example, like 50 percent of teachers in our sample she has previously used her smartphone to share digital content (videos, websites) with students to explain difficult concepts. Much like 80 percent of teachers who have used technology in classrooms before, she has used search engines (mostly Google) for content. Like 70 percent of her colleagues she has also used technology to improve her skills or take a training course and use Facebook or WhatsApp to communicate with teachers at her school as well as with those across schools. Just like 50 percent of other teachers she has used WhatsApp to communicate with parents.

Although Arifa owns a smartphone like 70 percent of other teachers, and like 95 percent of them has intermittent access to the internet, she feels like she is not as tech savvy and does not feel as confident as her male colleague in a nearby boy’s primary school to use technology. However, after attending a four-day long teacher training with TIP she feels a bit more confident about delivering the programme as planned by TIP. She feels she has acquired the necessary skills to get started but may need technical troubleshooting support every now and then such as when a network issue arises or if she has challenges related to logging into the TIP tech tool. She has benefitted a lot from other colleagues who modeled TIP tech use during the workshop.

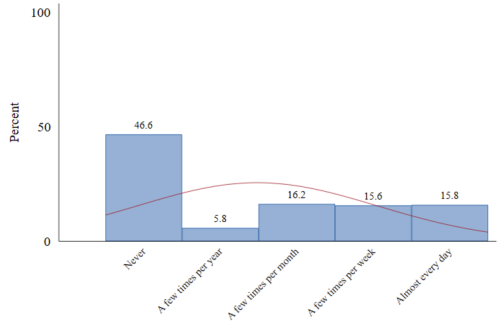

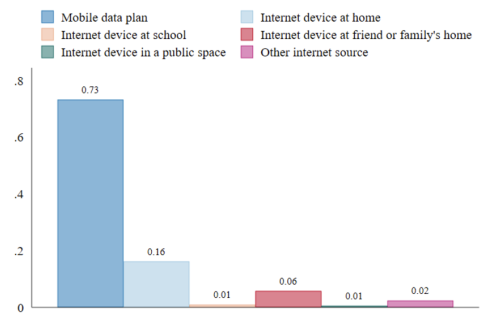

‘Babar’ is a 30-year-old primary school teacher at a boy’s school in urban Mardan, with a post-graduate degree. Like many young teachers, a post-graduate degree. he also reports being more confident than Arifa about basic smartphone skills. Like Arifa, he too occasionally uses it to share content from the Internet relevant to the lesson at hand. He pulls up websites using a search engine on his phone’s slow Internet connection when he can but accessing higher volume content, like videos, is not possible due slow and unreliable connectivity. That is why Baber will benefit from the TIP tech tool that allows offline access to educational videos.

Unfortunately, like most of his colleagues in the TIP pilot schools, Babar does not enjoy the convenience of having access to Wi-Fi at his school. Internet access is intermittent, and he relies on the spotty coverage of his cell phone service provider’s data plan.

‘Noor Alam’ is a senior teacher aged 54 who entered the teaching profession in the late 80s, when teachers were not required to hold a university degree. Noor Alam does not have a computer at home and began using the Internet after the cheap smartphone revolution when he was in his late 40s. His level of comfort using apps does not extend very far beyond using the YouTube and WhatsApp. He has an email address but uses it only when he needs to sign up for an account on a website. Since Noor Alam does not rely on Internet access for his daily life, he does not bother with a data plan and relies on free WiFi networks.

Unlike his younger colleagues, he has not benefited from the Government’s recently introduced blended induction training programme. Therefore, he has not received any direct or indirect digital training. Using the TIP tech tool for classroom instruction purposes will be his first experience of using digital content for his own training as well as for classroom management. While the four-day long teacher training with TIP gave him some practice in delivering the programme and using the tech tool, he remains reluctant to use technology and finds technical troubleshooting, Internet connectivity, and logging into accounts a nuisance.

We tested the TIP programme and the tech tool with many teachers. Through both qualitative and quantitative collected during product beta testing, a teacher training workshop with almost 5,000 teachers, and baseline surveys in 1,250 schools, we have gathered preliminary insights into tech adoption behaviors of TIP pilot schoolteachers. Teacher feedback, behaviors, and especially frustrations during this testing phase enabled us to gain some really useful insights into what may make or break adoption of the tech tool with our target population. These insights are both valuable from a policy perspective and were used to inform implementation of another version of this programme in the Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT). We summarise these insights using four categories described below.

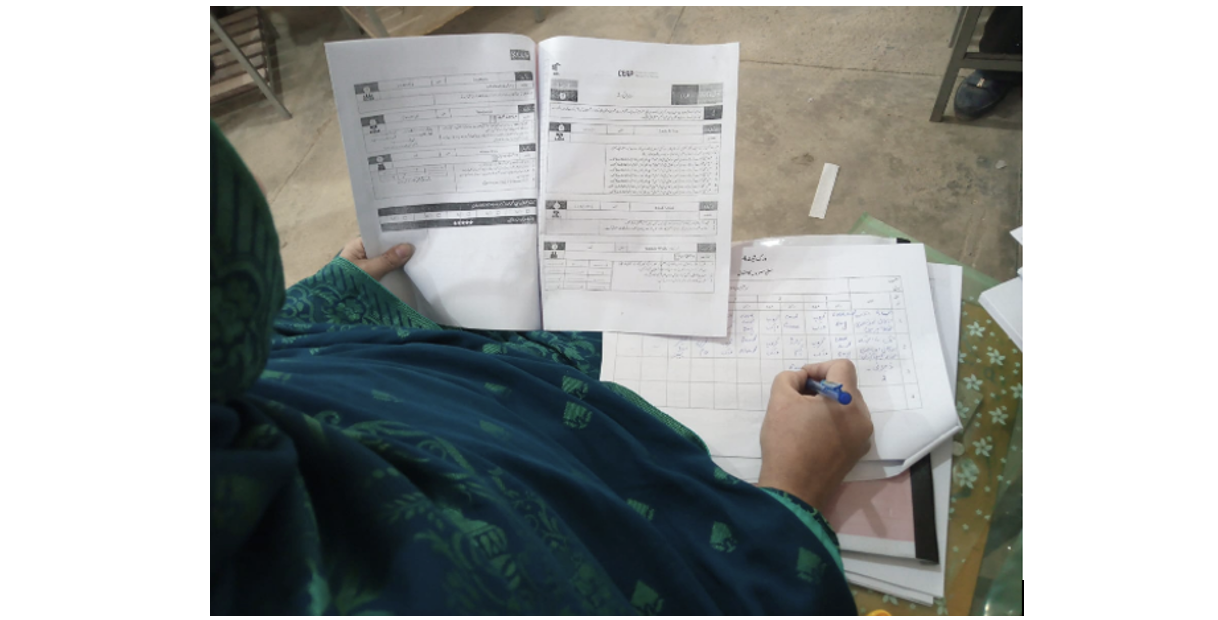

Teachers find comfort in maintaining paper records. We spent PKR 25 million on printing lesson plans and testing tools for teachers and students at 1,000 TIP treatment schools. That money could have been saved or spent on facilitating the tech tool usage had teachers been open to using electronic versions of these materials in the tech tool, in place of paper. They all asked for paper copies as well and took a long time to adjust to using only technology.

Teachers are reluctant to rely on what they can’t touch and see. During training, teachers remained reluctant to use tech directly to enter grades for fear of losing their marking record to technical glitches as well as because they were unsure about how their students might be ranked correctly by the sorting tool. So, they performed marking on paper and calculated total scores manually, instead of entering marks in the tool and letting the app do the calculations for them. One teacher agreed to try doing it the way it was recommended. After she finished, she excitedly exclaimed that it hardly took her a minute to do what the others were spending considerable time on. After hearing her, several other teachers said they wanted to try it too and realised that it saved them a lot of time and mental effort. They also validated calculations made by the app with their own paper-based calculation which gave them confidence in the accuracy of the app. So, peer modeling and training helps, although whether this behavior will persist remains to be seen. During a teacher training workshop, the experiential session on manual versus automatic grading and sorting of students was particularly helpful to teachers to help them realise the value of the tool.

Remembering the username and password becomes an unnecessary hurdle to adoption. Teachers kept forgetting their account information, found it hard to connect to a network or got frustrated when the network was poor, and data did not sync or download properly. All these small things pile up and create a barrier to adoption. However, the WhatsApp-inspired easy-to-use user interface of our Tech Tool has helped even more senior and less tech savvy teachers easily navigate the app once logged in.

Humans in general are hardwired to do only what is necessary to get the task at hand done. For example, during beta testing when teachers found out that they are only required to enter the diagnostic results for the app to sort students, they only entered diagnostic data and skipped checking off completed lesson plans and entering scores from quizzes. They would just check quizzes and do manual grouping for revision lessons, which took time. So, we added the ‘revision peer group formation’ feature in the app as an incentive to enter quiz results.

Similarly, we observed that teachers were only opening the app to enter required testing data and were not using other materials (lesson plans, training materials) in the tech app. We have now added visual prompts such as the watch videos instruction in red font as shown in the photo. This serves as an additional incentive for teachers to open the lesson plan module, despite having physical copies of the lesson plans.

Ultimately, most teachers understood the value of our tool. Some teachers who did not have personal smartphones at the time of training had even decided to purchase devices just to be able to use the tool. Others, in the control group with no technology access, persistently reached out to gain access to the tool to conduct the diagnostic activity.

We realised that once the programme is rolled out, teachers will still need some nudging to use the tech tool. So, we assigned one proactive teacher in each school as a ‘Tech Captain’ - someone who would make sure that teachers add data to the tech tool when they are required to do so as well as help resolve technology related issues such as helping with logging into the app or connecting to the Internet.

Once the TIP-KP programme rolls out ends, we expect to answer, with evidence, the following questions and more:

The evaluation of a version of this programme in the Islamabad Capital Territory zooms in on the role of technology in distributing content equitably, sustainably, and cost effectively. We expect to answer a broader series of questions even beyond technology uptake, including how empowering teachers and parents with information and guidance through technology can help their children improve their learning.

We would like to thank all our collaborators for supporting these projects, including RISE, the World Bank, Douglas B. Marshall Jr. Family Foundation, the EdTech Hub, the Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training and the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Elementary & Secondary Education Department (KPE&SED).

This blog was originally posted on the EdTech Hub site and has been re-posted with permission.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.