Clare Leaver

Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

Blog

Why do some students learn more in some schools than others? In the last two decades, standardized learning assessments such as PISA, ERCE, and TIMMS have helped us understand the state of student learning in education systems across the world, and have documented substantial variation both across and within countries. While there are many contributing factors at system, school, and household-level, one consideration receiving growing attention is school management—the processes and practices used by principals day-to-day as they run their schools. Currently, researchers interested in school management face two challenges: how to measure school management accurately and cost-effectively at scale across schools and countries; and how to explain any observed relationship between school management and learning outcomes in a way that elucidates the underlying mechanisms to guide policy. Our project addresses both of these challenges.

In our recent working paper, we develop a new approach to measurement that can be used with existing public data, and apply it to produce two new school management indices—a PISA-based index and a Prova Brasil-based index—that researchers can download and use immediately to study the role of management in education systems across a far wider range of countries and schools than was previously possible. We also develop a theoretical model that explains the consistent, positive link between school management and student learning in terms of incentive and selection effects among teachers, and incentives among students and parents. The predictions of the model are well-supported in our PISA data, and point to several areas for management reform in public schools, particularly around the use of people management (teacher appraisals), and operations (quality promotion in the classroom, school reviews). Schools that get these practices right experience fewer teacher shortages, and report more motivated and hardworking teachers, students and parents, all of which contribute to better learning.

Management used to be viewed as an unmeasurable “productivity shifter,” to be relegated to the residual in any performance regression. Over the last decade, improvements in survey methodology and data access have allowed for advances in measurement. The current “state of the art” approach uses a dedicated survey—the World Management Survey (WMS)—to measure establishments’ adoption of structured management best practices. But, while the WMS offers uniquely rich information about management practices, it costs approximately USD400 per interview and takes about four months to conduct a single country wave. In view of these high costs, the WMS has only been undertaken in the education sector of a small set of countries to date: eight using the original WMS schools methodology (Brazil, Canada, Great Britain, Germany, Italy, India, Sweden, USA) and eight using the D-WMS, a version adapted to low income settings (Andhra Pradesh, Brazil, Colombia, Haiti, Mexico, Mozambique, Pakistan, Tanzania).

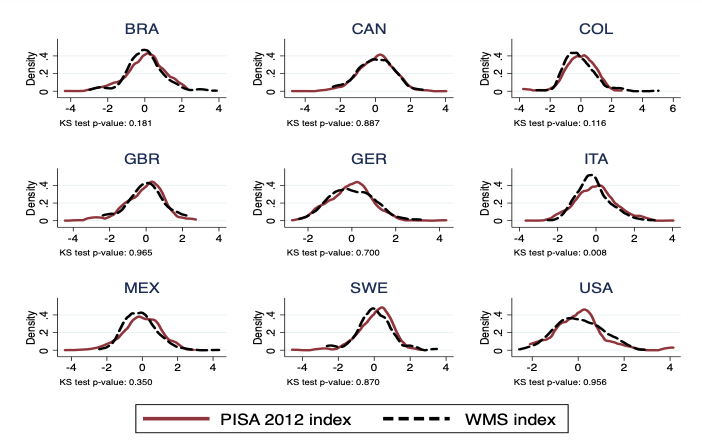

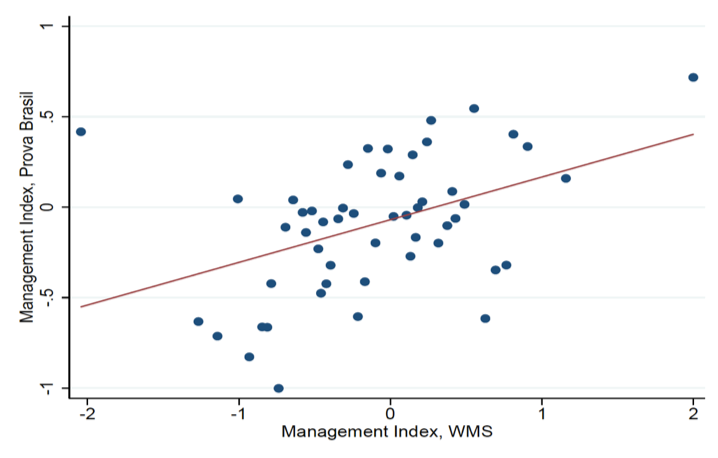

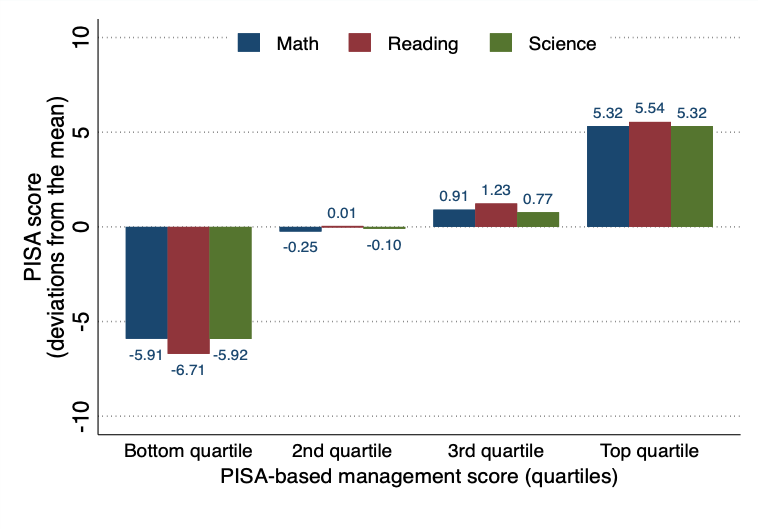

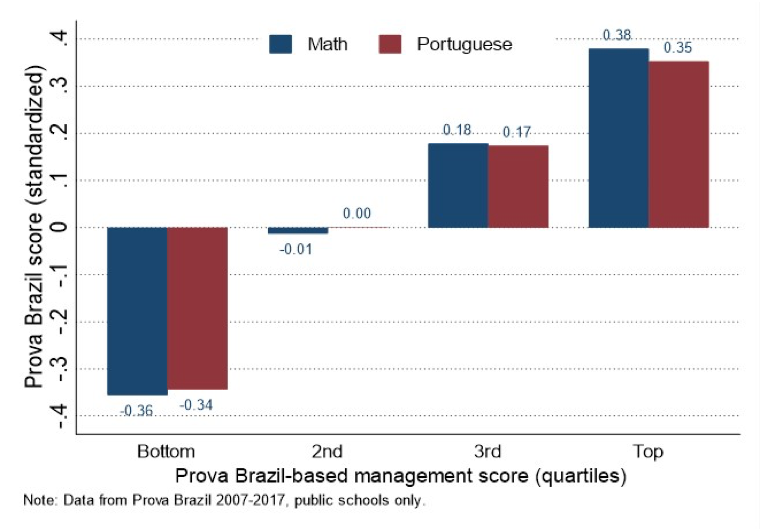

Our new approach to measurement can be used with existing public datasets containing question items about school management. To illustrate, we have applied it to two popular public datasets: the OECD's Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), and the Brazilian school census survey, Prova Brasil. Our PISA-based index covers over 15,000 schools across 65 countries, and our Prova Brasil-based index covers nearly all public schools in Brazil. We validated these new indices against the World Management Survey, and they hold up well (Figure 1). And, consistent with previous research using the WMS in schools, both indices show a strong, positive relationship between school management and student learning (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Validation of new management indices against WMS

(a) PISA-based management index vs WMS

(b) Prova Brasil-based management index vs WMS

Figure 2: New management indices and student performance

(a) PISA-based management index and student performance

(b) Prova Brasil-based management index and student performance

The association between school management and student learning in Figure 2 is not trivial. Schools in the bottom quartile of their country’s PISA management index score about 6 points below the PISA global mean, while schools in the top quartile of their country’s PISA management index score about 5.5 points above the PISA global mean, a gap of approximately four months of learning. These PISA results, and those for Prova Brasil, reinforce earlier findings using the WMS and data from randomized controlled trials in the U.S.

Given this evidence, we turned our attention to the second challenge: understanding why management matters in schools. Our working paper sets out, in general terms, how the impact of school management can be decomposed into learning gains that arise because given actors (teachers, students and parents) become more productive, and learning gains that arise because different actors join the school. To explore why these incentive and selection effects might arise, we developed a specific model that captures key features of education systems in Latin America.

This model has two main building blocks. The first is the education production function: we assume that student learning depends on teacher ability, teacher effort, and household effort. The second is the impact of management practices where, considering the personnel policy restrictions the public sector faces, we distinguish between operations and people management. Put simply, good people management practices enable managers to observe and contract on the performance of their employees, as well as to cultivate intrinsic motivation. Good operations management practices enable managers to use resources efficiently and hence offer a higher level of teacher compensation and a more stimulating environment for students.

Our framework predicts that good people management practices increase expected test scores via teacher selection and incentives, which result in fewer teacher shortages, and higher teacher motivation and effort. Good operations management practices are predicted to increase expected test scores via teacher selection and household incentives, which result in fewer teacher shortages, higher teacher motivation and effort, and greater household effort.

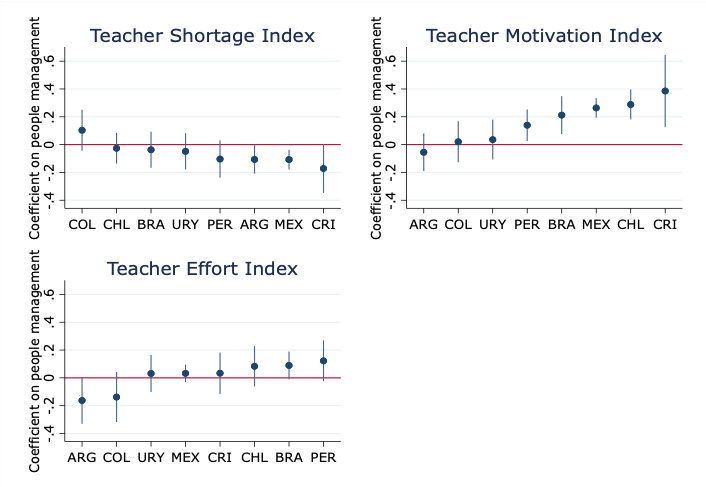

We focus on Latin American countries and find strong support for these predictions in our PISA data. Principals in schools with higher PISA-based people management scores (predominantly private schools) are less likely to report experiencing teacher shortages and also report higher levels of teacher motivation and effort, compared to principals in schools with lower PISA-based people management scores.

Figure 3: People management and intermediate outcomes in public and private schools

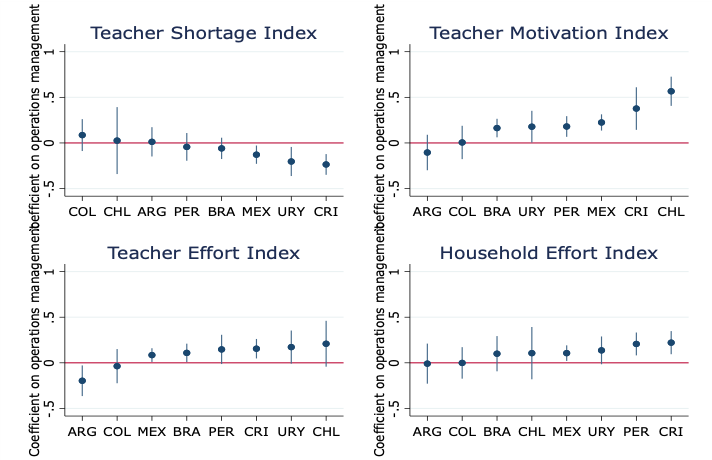

Figure 4: Operations management and intermediate outcomes in public schools only

In turn, principals in public schools with higher PISA-based operations management scores are less likely to report experiencing teacher shortages and also report higher levels of teacher motivation, teacher effort and household effort, compared to principals in public schools with lower PISA-based operations management scores.

While not definitive causal evidence, this combination of theory and descriptive empirical analysis offers a novel insight into why management matters in schools. People management practices such as performance pay, while common in the private sector, may not be possible in public schools. But there would seem to be fewer barriers to conducting assessments to judge teacher effectiveness, and letting such appraisals lead to changes in public recognition, opportunities for professional development, likelihood of career advancement, and/or greater responsibilities. That is, these people management practices help to attract, develop and reward good performers, and, our analysis suggests, should improve both teacher selection and incentives.

There is also substantial variation in the strength of operations management practices within the public sector. This suggest a role for government to encourage principals in public schools with weak operations management to follow best practices. Specific areas suggested by our analysis include processes that facilitate: personalization of learning; dialogue among staff, students and parents focused on continuous improvement; and collection and use of student assessment data.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.