Fredo Bankole

Institute for Empirical Research in Political Economy (IERPE)

Blog

When people are educated, they are more likely to participate in politics. But this relationship depends on the type of political regime in place in the country. In non-democratic regime, increased education level may not lead to political participation.

This blog explores the relationship between educational attainment and political participation using evidence from RISE data collection in Nigeria. This relationship has been explored in numerous countries utilizing a wide variety of methodologies. Bömmel and Heineck (2020) find that schooling reform (an extension of compulsory schooling from eight to nine years and a shift of the start of the school year from spring to autumn) did not stimulate political participation through education attainment. In contrast, Larreguy and Marshall (2016) find that Nigerians with higher levels of education are more attentive to politics.

The relationship between educational attainment and political participation may also be dependent on the type of political regime in place. Croke et al. (2016) use data from Zimbabwe to argue that increased education levels can lead to decreased political participation under authoritarian or ‘non-democratic’ regimes. This is because more educated people tend to be more critical of authoritarian governance and often support democracy. They may believe that their political participation corroborates the power of an authoritarian regime. As such, they prefer not to participate in politics in this context.

In this blog, we seek to study the causal relationship between educational attainment and political participation in western Nigeria. We rely on a similar methodological approach to Osili and Long (2008), who studied the causal relationship between women’s fertility in Nigeria and their level of education, and Bömmel and Heineck (2020), who used exogenous change brought by an educational reform as an instrument to measure the causal relationship between education and political participation while correcting for the endogeneity bias of the education variable. The reform we will rely on as an instrument is the Free Primary Education (FPE) program implemented in Western Nigeria from 1955 to 1965.

Our analysis utilizes data collected by the RISE FPE Project from research participants who were of primary school age (including both school children and non-school children) during the time of the FPE program in western Nigeria, from 1950 to 1970. Data collection took place in western Nigeria where the reform was implemented, in bordering areas of Nigeria where the reform was not implemented, and across the border in the region of Benin bordering Western Nigeria, which shares linguistic, cultural, and economic ties with western Nigeria. Information was collected on a sample of 3,340 subjects total across these regions.1

In this blog, we present results from an instrumental variable estimation focusing on the 1,853 subjects who lived in Nigeria at the time of the FPE. Our main outcome variable is political participation, an indicator variable defined as being active in politics, being a member of a professional association, being a head of a community, or being a traditional chief. Of course, political participation goes beyond this narrow definition and may also include voting, participating in peaceful demonstrations, etc. The team did not collect data on these metrics as part of the FPE project – this is one limitation of our analysis.

The key explanatory variable is whether a research participant is ‘at least primary educated’ (meaning they graduated from primary school). Additional explanatory variables include gender, religion, social network (having a political leader in one’s family or having an intellectual in one’s family), state of residency, and ethnicity. We follow the example of Bommel and Heineck and use exposure to an education program as an instrumental variable (the FPE program in our case). Although being exposed to the FPE program is correlated with the educational attainment of individuals, it is exogenous their political participation (it should not impact political participation except through the mechanism of increased education).

Nigeria is a major oil and gas producer and the most populated country in Africa. Its population is extremely diverse in terms of religion and ethnicity. Since its independence in 1960, Nigeria has oscillated between military and democratic rule, undergoing ten military coups. Democracy was instituted in 1999 and since then federal elections for its presidency, senate and house have been used to determine political representation (Larreguy and Marshall, 2016).

Despite this change in regime, Nigerian political institutions are weak and voters are characterized by low demand for vertical democratic accountability (Bratton and Logan, 2006). (Wantchekon and Jensen, 2004) state that “from 1965 to 1990, nearly all African low-income countries, including the resource-dependent countries, were authoritarian including Algeria, Nigeria, Libya, Gabon, Cameroon, and the former Zaire”. Thus, Nigeria’s political context was characterized by a non-democratic regime during our period of study, the time of the FPE program. This insight into the political context of Nigeria can help us to interpret our results.

We utilize Pearson chi2 tests to assess the correlation between our explanatory and outcome variables. Our data shows a correlation between the variable ‘at least primary educated’ and the political activeness variable (Pearson chi2(1) = 10.3297; Pr = 0.001) and between ‘at least primary educated’ and membership in a professional association (Pearson chi2(1) = 40.3439; Pr = 0.000). The data also shows a correlation between our education variable and being a traditional chief (Pearson chi2(1) = 14.8869; Pr = 0.000). That said, there is no correlation between our education indicator and ‘being head of a community’ (Pearson chi2(1) = 0.0215; Pr = 0.884).

While these correlations are revealing, a key technical challenge in determining whether increased education causes increased political participation in Nigeria is that an OLS regression estimate or Pearson chi2 test cannot provide conclusive evidence on the causal relationship between the variables of interest. This is because our education variable may be correlated with other unmeasured characteristics (such as family background, social norms or community wealth) that could also impact political participation. In other words, those who are more educated might also be more likely to have other characteristics that lead to differing levels of political participation. Thus, we may observe a correlation between education and political participation that is in fact caused by these other characteristics.

Using exposure to the FPE program as an instrumental variable can help us to overcome this endogeneity challenge. Assuming that the FPE program does not have any direct effect on political participation, other than through the channel of increased educational attainment, we can use exposure to the FPE program as an instrument to analyze the causal impact of educational attainment on political participation. We perform a two stage least squares (2SLS) analysis of the political participation variables on our education variable (‘at least primary educated’).

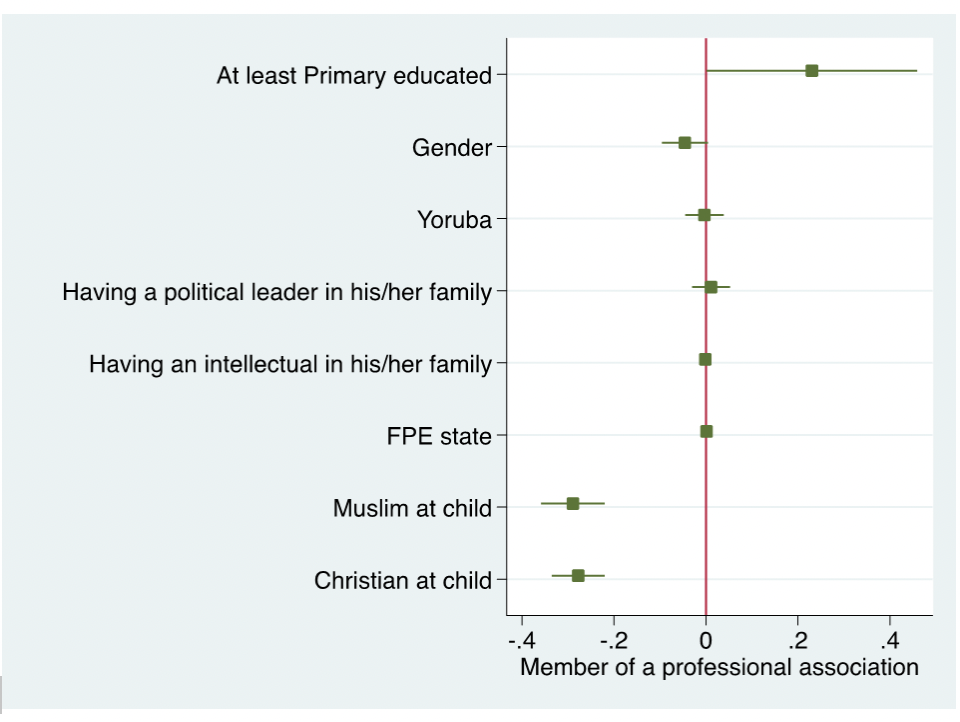

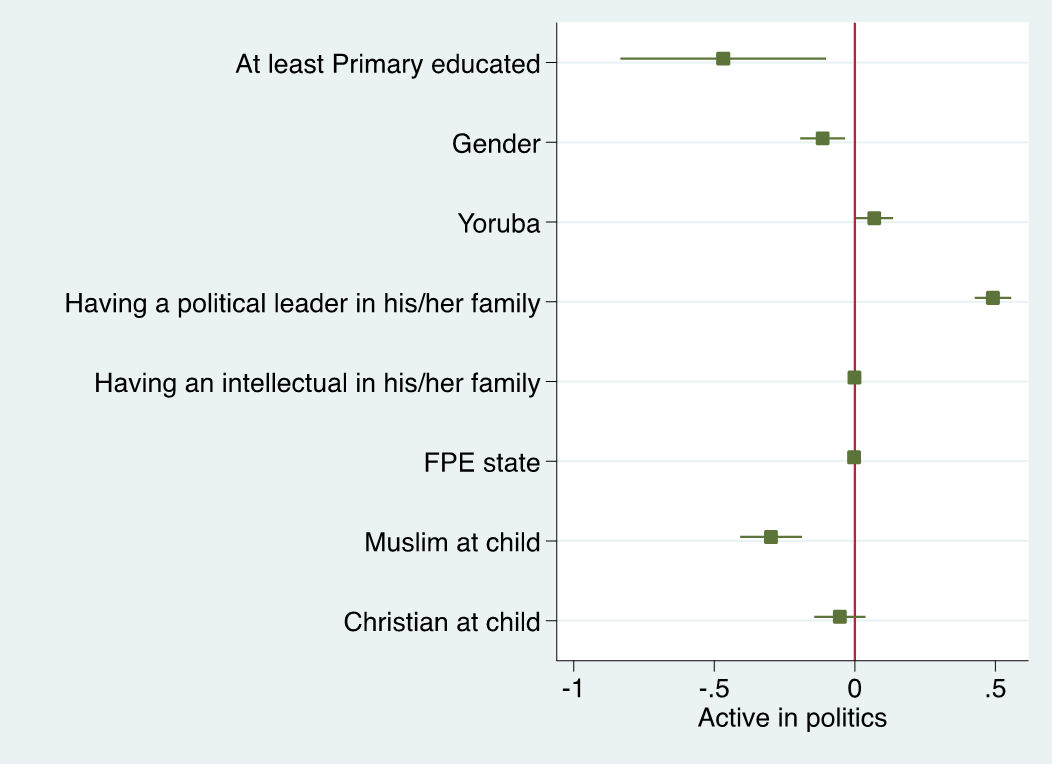

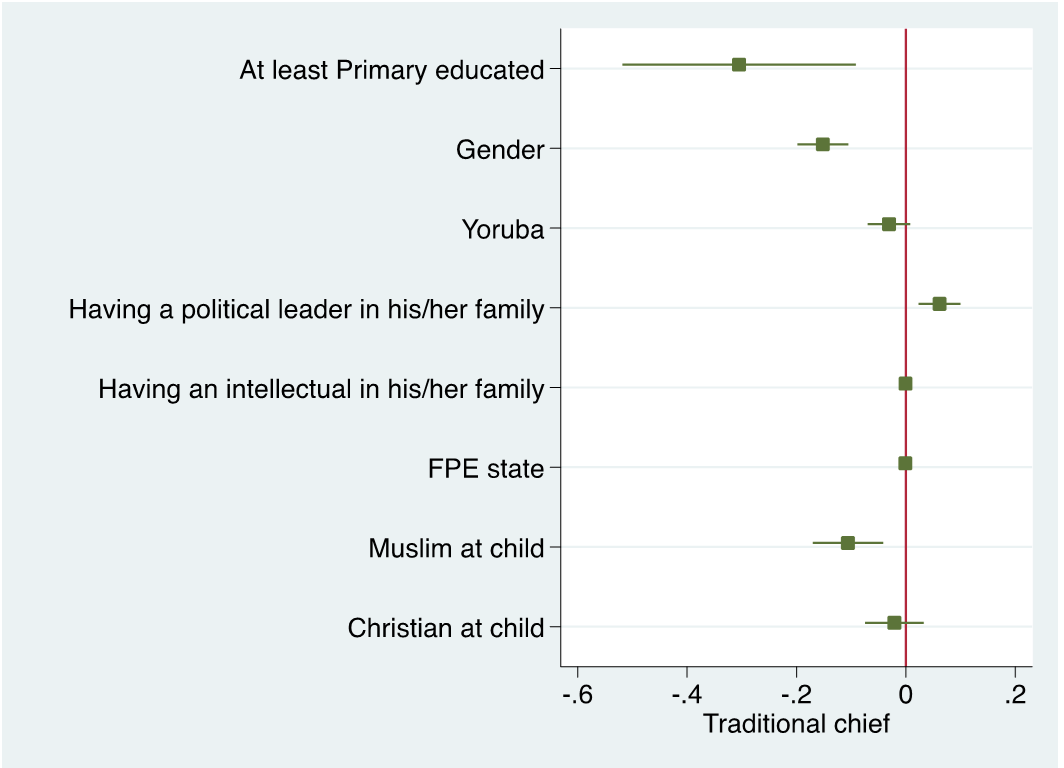

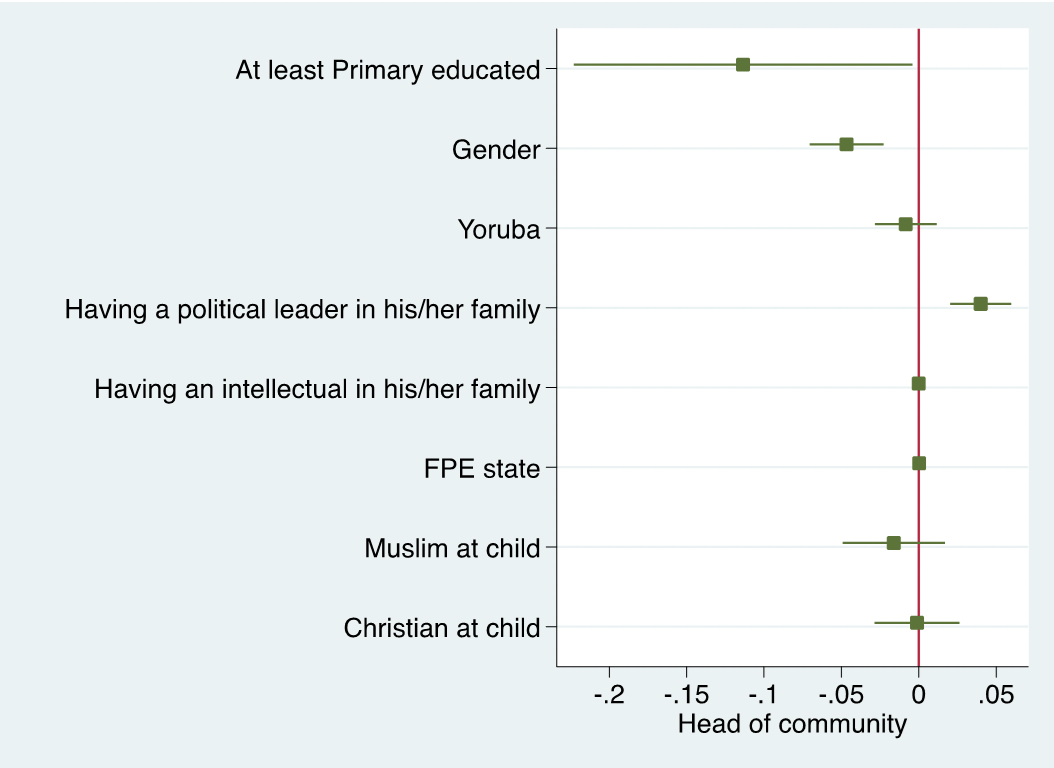

Results from this analysis are shown in the figures below. In all of the figures, our key explanatory variable is ‘at least primary educated’. The location of the horizontal line indicates the magnitude of the impact education had on political participation in terms of percentage points. Being on the left side of the vertical line indicates that the coefficient is negative whereas the right side indicates positive coefficients. The length of the horizontal line is the 95% confidence interval. If the horizontal line crosses the vertical line, then the impact of this explanatory variable on political participation is not statistically significant from zero.

Figure 1 illustrates that having a primary education is associated with a 23 percentage point increase in the likelihood of becoming a member of a professional association. Educated subjects are more likely to be members of professional associations, and the result is statistically significant (p<0.05).

As shown in Figure 2, having at least a primary education is associated with a reduction in the likelihood of being politically active of 46 percentage points. This result is highly statistically significant (p<0.05) and indicates a strong relationship between these variables. This revealed relationship fits Croke et al.’s hypothesis that higher levels of education lead to decreased political participation under authoritarian regimes.

Figures 3 and 4 depict similar results to Figure 2. The educational attainment variable is negatively correlated with the community participation variables (traditional chief and head of community). Having a primary education decreases the probability of being a traditional chief and being a head of a community by 30 percentage points and 11 percentage points, respectively (p<0.01 and p<0.05). Assuming our instrument is valid, the fact that the 2SLS results are significant suggests a causal relationship between these variables. Research participants who have attained at least primary education are less likely to hold traditional community leadership posts.

Our analysis provides some evidence that research participants’ level of political activeness is likely to be predicated on their level of educational attainment within our study area. Completion of at least a primary school education was correlated with lower levels of political participation in the majority of our analyses. These results align with the results of Croke et al. (2016) in the sense that when people are more educated , they are less likely to participate in politics (including community participation) if the local political regime is not ‘’purely democratic’. As outlined in our brief background section on Nigeria’s political context, the period targeted by our study was marked by an authoritarian regime in Nigeria. If we believe the hypothesis of Croke et al., this might explain the reason why people educated during that period are less interested in participating in politics.

The positive relationship between education and professional association membership is more difficult to explain given the results of our other analyses. One possible explanation is that while education does not lead to increased political participation, for the reasons mentioned above, it could lead to increased interest in discussing professional issues to advance one’s career, which is in alignment with support for democracy and does not serve to legitimize authoritarian rule. It also makes sense that the more people are educated, the more they might want to get involved in labor negotiations, which are a key function of professional associations.

Although this analysis gives some insight on the relationship between education level and political participation, and the use of instrumental variable regression means we should theoretically be able to draw causal conclusions from our data, it has some key limitations. The first limitation is that our data collection took place only in the western region of Nigeria and thus cannot be generalized to other regions. The second limitation is the political participation variables we were able to use (being active in politics for instance), which do not include key aspects of political participation like voting and participation in political demonstrations. Additional data collection including these types of variables can lead to a stronger conclusion on the relationship between education and political participation in this area.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.