Yue-Yi Hwa

Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

Blog

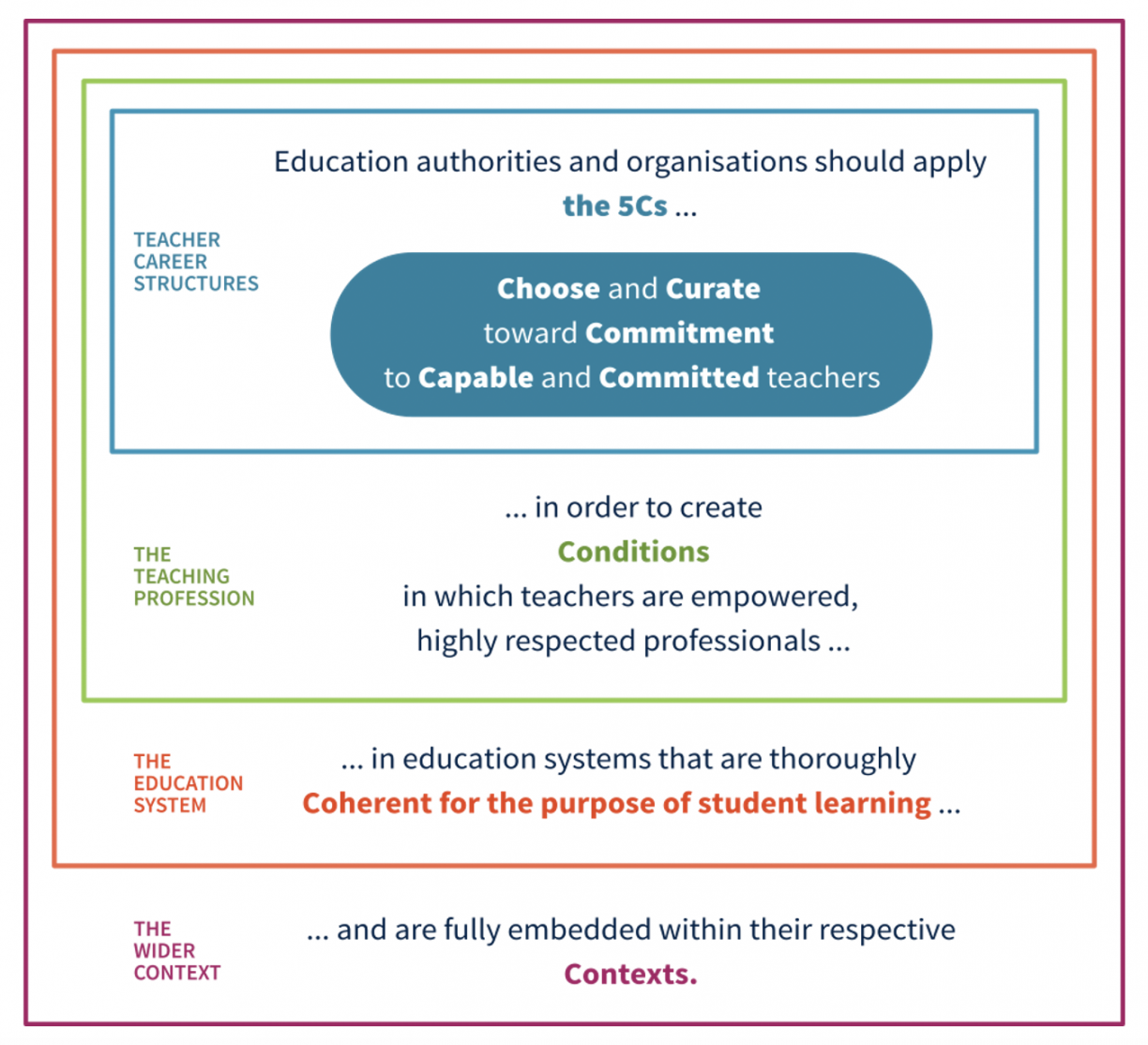

How can education systems develop teachers who are empowered, highly respected, strongly performance-normed, contextually embedded professionals who cultivate student learning? New research from the RISE Programme proposes the 5Cs as a set of principles for building toward that vision.

From the time a young person enters an initial teacher education programme to the time they retire as a veteran educator, a teacher’s career is shaped by countless interactions with a wide range of people, processes, and resources—including varied cohorts of students, fellow teachers, school leaders, and district officers; as well as administrative requirements, school leaving exams, curriculum revisions, and textbook updates. Put differently, teaching and teacher careers are complex.

In a new primer* for the RISE Programme, Lant Pritchett and I try to make sense of this complexity by synthesising research related to teacher careers from across a range of academic disciplines and country contexts. This synthesis culminates in a set of principles that we call the 5Cs, as reflected in the title of the primer: Teacher Careers in Education Systems That Are Coherent for Learning: Choose and Curate Toward Commitment to Capable and Committed Teachers (5Cs).

Underlying the 5Cs is a vision of empowered, highly respected, strongly performance-normed, contextually embedded teaching professions that cultivate student learning. This may not yet be the reality in many education systems around the world, but we hope that it can be and believe that it should be—children everywhere deserve such teachers. We offer the 5Cs as a set of principles for building toward this vision.

Here’s a brief overview of each of the 5Cs:

| The 5Cs | What they imply |

|---|---|

| Choose … | Education authorities and organisations should initially choose teachers based on their potential capability and commitment to cultivating student learning. |

| … and Curate … | The novice phase of teaching should be viewed as a period of curation, during which there is ongoing attention to teachers’ professional development—and also to identifying those teachers who are most willing and able to make careerlong contributions to children’s learning. |

| … toward Commitment … | After the initial curation, education authorities and organisations should make a long-term employment commitment to those teachers who have demonstrated capability and commitment in classroom practice. |

| … to Capable … | Effective teachers need to be technically capable and equipped for cultivating student learning in their specific school, classroom, and curricular contexts. |

| … and Committed teachers | Teachers also need to be motivationally committed to the systemwide goal of cultivating student learning. |

In the primer, we discuss each C at length, explaining why it matters for teacher careers, and how it contributes to the 5Cs as a coherent set of principles for teacher careers that cultivate student learning.

Among the 5Cs, probably the most contentious C is ‘curate’: the principle proposing that the first few years of teachers’ careers should be a meaningful probation period, in which novice teachers are extensively supported to develop their capability and commitment to the teaching profession—and during which they are offered straightforward pathways to voluntarily leave the profession if it becomes clear that they are unlikely to thrive in teaching long term.

Yes, curation can be costly. Teacher turnover causes frictions in the distribution of teachers across schools and classrooms. Training pre-service teachers who don’t ultimately stay in the profession substantially increases the teacher education budgets of education ministries. And, at the individual level, switching occupations can incur a lot of emotional, logistical, and financial costs.

Yet, as we argue in Part 3 of the primer, these costs are worthwhile—because the alternative is paying a premium for a stable but not necessarily effective and probably not purpose driven corps of civil service teachers.

Prior to writing this primer, Lant (an experienced development economist) was already convinced of the value of early-career curation in teacher careers, having written about it in the context of the Indian education system in previous papers co-authored with Varad Pande and Rinku Murgai.

In my case, it took me (an early-career education researcher) a while to be convinced that curation was really worth its high costs. What changed my mind?

And I’m now fully convinced that curation matters. In short: if we really believe that teaching is a complex task—which it undoubtedly is, not only because human cognitive development is influenced by so many factors, but also because classrooms are open systems that are affected by everything from national-level political decisions to whether any given student feels focused or hungry or sleepy or antsy—then we should also accept that no prospective teacher can know with 100 percent certainty how much they will thrive in the classroom until they have had an extended period of time to experience firsthand how they interact with the challenges and thrills of classroom teaching.

For a much more detailed version of this argument, see Part 3 of the primer. For a slightly more fun version, see this TED-style talk that I recently gave about the 5Cs:

To make the 5Cs a bit more concrete, we also propose five ‘premises for practice’, which suggest possible action areas for education authorities and organisations that are considering teacher career reform. We will discuss starting points for other education stakeholders in subsequent publications.

| Typical approach | 5Cs approach | Premises for practice |

|---|---|---|

| Assume that the education system is independently committed to learning. | Articulate and prioritise a core purpose that is oriented toward student learning so that teachers can be capable of, and committed to, fulfilling that core purpose collectively. | Premise for practice #1: Clear, consensus-based prioritisation of learning, delegated from education authorities and organisations to schools and teachers, is fundamental to teacher career reform. |

| Don’t pay any particular attention to the novice phase. | Recognize that professional norms developed during the novice phase—including the norms that are implicit in processes for choosing, curating, and committing to teachers—can shape teachers’ careerlong beliefs about what it means to be a capable and committed teacher. | Premise for practice #2: Contextually embedded, learning-oriented teacher professional norms must be cultivated throughout the novice teacher phase. |

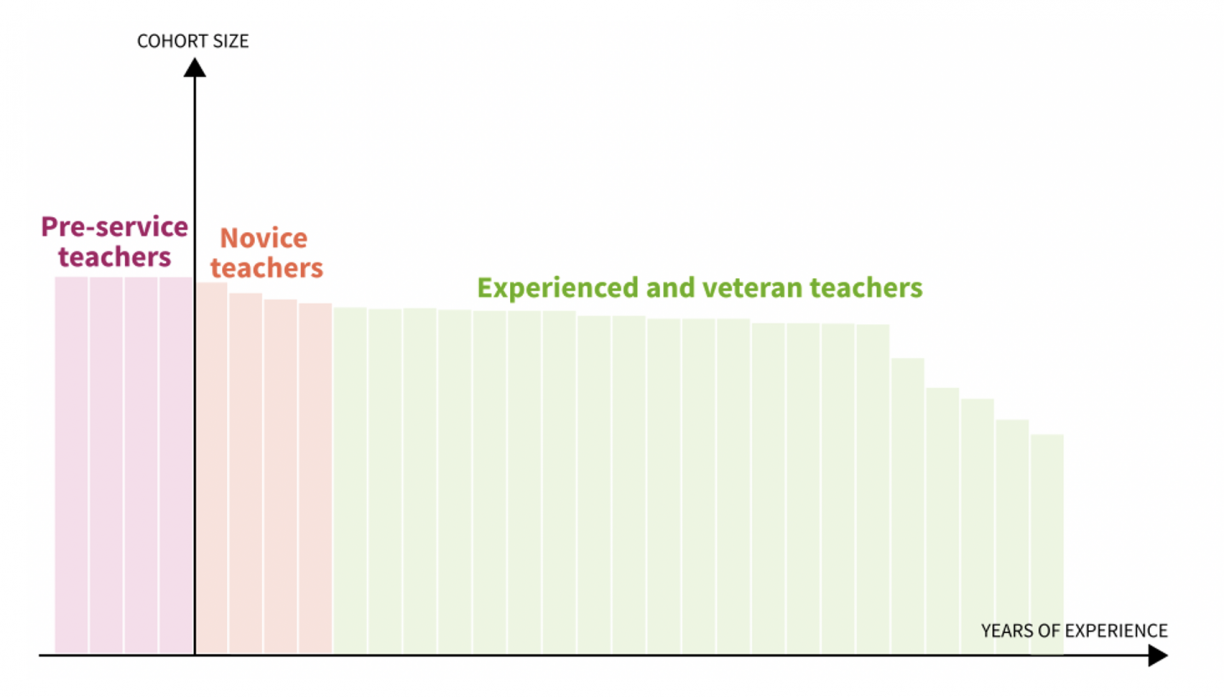

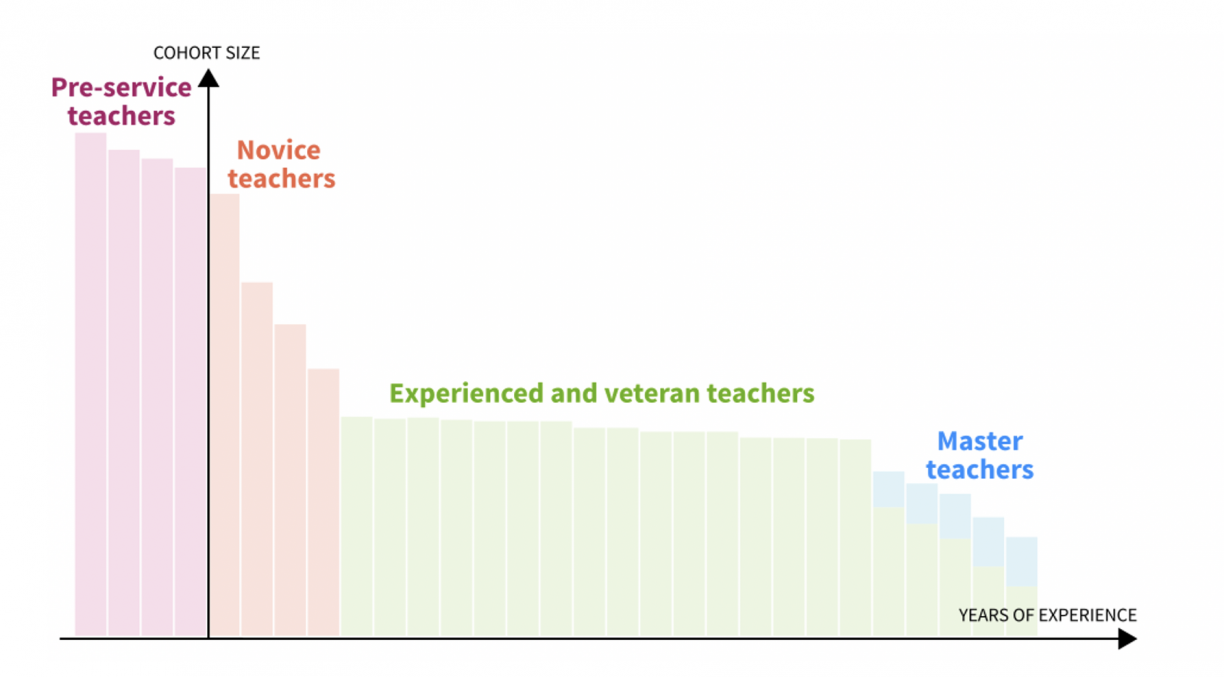

| Award permanent job tenure from day 1. | Prior to a permanent employment commitment, include curation in the pre-service and novice phases so that both employers and teachers have the opportunity to discern, through engagement in classroom practice, whether they will be capable and committed to classroom teaching long-term. | Premise for practice #3: The pre-service and novice phases should be a period of curation, such that, as with nearly all other professions, a substantial proportion of initial entrants do not persist in the career. |

| Rely on EMIS indicators, years of service, and formal certifications as the main (or only) sources of information about teaching quality. | Earmark resources for ‘thick’ information systems and extensive professional support so that teachers have the best chances of being capable and committed in the complex work of classroom teaching, and education authorities and organisations can make the best possible choices about whom to employ long-term. | Premise for practice #4: Education authorities and organisations should invest in building multi-component ‘thick’ information systems about teaching quality and in supporting teachers to continually improve their pedagogical competencies. |

| Define fairness in teacher compensation in terms of seniority (and perhaps formal qualifications and responsibilities). | Make decisions about compensation, as with all other aspects of teacher careers, based on the goal of cultivating capable and committed teachers who, in turn, cultivate student learning. | Premise for practice #5: Fairness in teacher compensation should be defined based on what, in the specific context, will attract, retain, and motivate capable and committed teachers who make the best possible contributions to student learning. |

To be clear, we don’t think that the 5Cs are the be-all-and-end-all for quality teaching and learning in education systems. This is partly because the 5Cs are a set of principles that should be applied differently in different contexts, and also because the 5Cs focus on teacher career structures, which are a subset of the factors shaping the conditions in which teachers act and teach, which in turn are a subset of education systems and their wider contexts.

Also, we certainly don’t think that the 5Cs can or should be the last word on teacher career structures. Far from it. Instead, through this primer we hope to contribute to ongoing discussions that aim to inform improvements in teacher careers in order to better serve the children in our education systems. Here’s hoping for good conversations and for better teacher career structures, for the sake of teachers and students alike.

Note: all of the tables and figures in this blog are taken from the primer, Hwa & Pritchett (2021), Teacher careers in education systems that are coherent for learning: Choose and curate toward commitment to capable and committed teachers (5Cs).

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.