Marla Spivack

World Bank

Blog

By ensuring that all girls are receiving inclusive, effective instruction in well-functioning education systems, we can grow closer to achieving SDG 4’s promise of universal literacy and numeracy and lifelong learning.

Today is International Women’s Day. Among the unprecedented challenges that COVID-19 presents, there are many, many, many issues in women’s lives that deserve urgent attention. Amid all of those pressing challenges, we should not lose sight of how COVID-19 is affecting today’s girls, who will become tomorrow’s women.

COVID-19 has closed schools. According to UNESCO, nearly 1.5 billion children in more than 180 countries were affected by the closures. For girls with access to the internet, this means time spent in front of screens, where too little is known about how the abrupt transition to online learning will affect their progress. But for girls in disadvantaged countries and communities who lack access to the technology that enables remote schooling, school closures have severely curtailed or even completely paused their learning.

Fortunately, schools are starting to open up again. This is welcome news. But school systems will have to act quickly to help girls catch up from this lost year of learning. Simulations and empirical estimates suggest that when children miss out on time in school, they can continue to fall farther behind after they return, if insufficient attention is paid to ensuring that classroom instruction matches children’s actual, post-lockdown learning levels rather than simply defaulting where the curriculum would have been under business as usual. Education systems need to focus on foundations when schools reopen, assess where students are when schools reopen, provide adequate time for remediation, and streamline curricula so that children don’t fall farther behind when they are back in the classroom.

Those are the immediate steps systems can take to help children catch up from this crisis, but the reopening of schools is also the right time to ask: what kind of school systems are girls returning to?

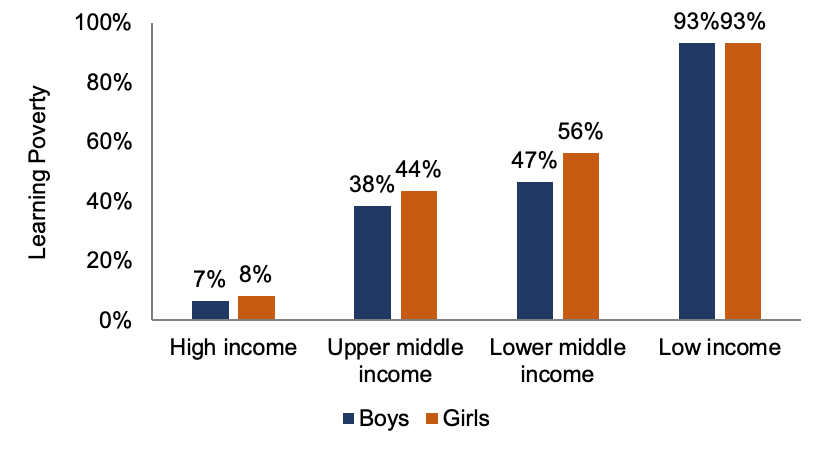

The World Bank’s Learning Poverty measure paints a stark picture of the poor quality of the education most children in low- and middle-income countries receive. 53 percent of boys and girls in low- and middle- income countries reach the age of 10 without mastering basic reading skills. In the world’s poorest countries, the figures are even more grim, as Figure 1 shows.

Note: The learning poverty indicator is the share of children at the end of primary age below minimum reading proficiency adjusted by out of school children. Source: Learning Poverty (October, 2019), The World Bank and UNESCO Institute of Statistics.

Though the aggregate learning poverty figures in Figure 1 show girls doing a little bit better than boys in all but the poorest countries, the relative performance of boys and girls varies by country and subject. But “doing better” is relative. Both boys and girls are doing extremely poorly, so whether you pick a country and a subject where girls are doing a little bit better or a little bit worse, girls are still overwhelmingly being left behind from the goal of universal basic literacy and numeracy.

For example, in a forthcoming paper (“Learning Outcomes in Developing Countries: Four Hard Lessons from PISA-D”) Lant Pritchett and Martina Viarengo estimate that across the 7 countries that participated in PISA for Development girls do 9.3 PISA points better in reading than boys, and 15.2 points and 5.9 points worse on math and science, respectively. But, overall just 12.6 percent of girls in those countries are reaching the SDG for reading.

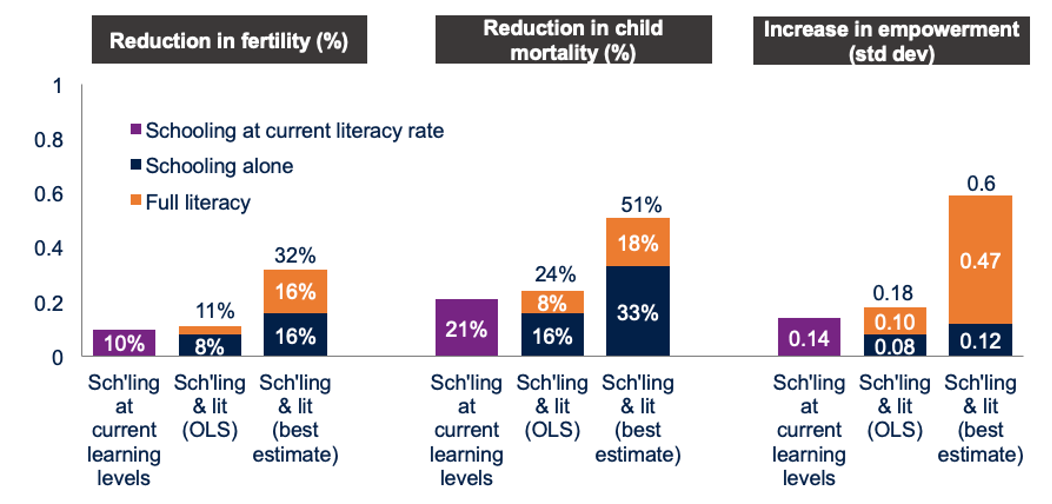

This is a tragedy not only for today’s girls, but also for tomorrow’s women. The benefits of girls’ schooling are well established, but a recent RISE working paper shows that those estimates might be selling the benefits of education short. Michelle Kaffenberger and Lant Pritchett show that the benefits of education in terms of reduced fertility, reduced child mortality, increased empowerment, and better financial practices are even greater than most existing estimates would lead us to believe. This is because most estimates only account for the returns to schooling—but the returns to the combination of schooling and learning are larger.

Source: Figure from Spivack (2020), “Quality Education for Every Girl for 12 Years” based on analysis from Kaffenberger et al. (2020), “Women’s Education May Be Even Better than We Thought: Estimating the Gains from Education when Schooling Ain’t Learning.”

What can be done to ensure that tomorrow’s women enjoy these benefits? With education outcomes that are so poor, incremental improvements are not enough. Systemic change is needed to improve outcomes for girls.

The first step towards ensuring girls get the education they deserve is getting them into school. Recent analysis from colleagues at the Center for Global Development (CGD) shows that girls’ schooling has increased dramatically over the past 50 years. Girls are still overrepresented among out-of-school children—UNICEF estimates that 55 percent of the world’s 59 million out of school children are girls. Moreover, girls can still expect to receive fewer years of education than boys, but the CGD report also shows that these gaps are narrowing and tend to get narrower as overall education and countries’ wealth rise.

Every girl has a right to attend school, and adequate early childhood education and on-time enrolment in school are critical first steps towards girls’ learning. However, universal enrolment alone won’t ensure we reach the crucial goal of universal literacy and numeracy.

Simulations using Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data on women’s schooling and literacy in 51 countries can show the gains in literacy we would expect to see if all women had the opportunity to complete primary school (meaning finish Grade 6). In other words, what would happen if the women who hadn’t finished primary school knew as much as their peers who had?

The results of these simulations vary by country. In places where many girls are out of school, and where learning profiles—the learning that children gain for each year spent in school—are reasonably steep, a world in which all girls complete primary school would produce a population of women with much higher literacy rates. This is the case in Ethiopia, where the literacy rate among women would rise from 18.1 percent to 75.2 percent1 if all girls were to complete primary school. But most countries’ simulated results did not show as large an increase, because the learning profiles in these countries are too flat. Overall, across the 51 countries, universal primary completion would reduce illiteracy by 17 percentage points, leaving 39 percent of women still illiterate.

Both universal enrolment and universal learning are crucial.

Sustainable Development Goal 4 highlights the fact that lifelong learning and universal literacy and numeracy go hand in hand. That is because foundational skills, like basic reading and math, are the building blocks of more complex learning.

To ensure that women gain the literacy and numeracy they need to be lifelong learners, girls must master foundational skills early. Failure to master foundational skills, combined with a curriculum that continues to advance and leave its students behind, is a major cause of flat learning profiles.

Reforms that prioritise universal, early, conceptual and procedural mastery of foundational skills can play a pivotal role in raising learning outcomes for girls, and unlocking their success in secondary school and beyond.

Incoherence among core components of the education system is a common stumbling block that hinders foundational skill development. For example, in many education systems, the curriculum, assessments, and instructional practices are misaligned. This sends mixed signals to teachers, who may be torn between teaching to tests and following the curriculum, and undermines students’ learning. Likewise, many systems struggle with a misaligned curriculum that either moves too fast or doesn’t devote adequate time and attention to mastery of the basics.

Systems can address this problem by pursuing reforms that are 1) contextually appropriate reforms, 2) set clear learning goals that are coherent with children’s current learning levels, 3) develop instructional approaches that align with children’s current learning levels and target their learning progress, and 4) provide effective support to teachers. Reforms that fit with those four ALIGNS (Aligning Levels of Instruction with Goals and the Needs of Students) principles have been shown to significantly increase learning for students in school—replacing those flat learning profiles with the continually increasing levels of learning that all children deserve.

Reforms like these, that shift systems towards greater coherence for learning, are reforms that promote inclusion, as they ensure that all children progress in their learning during their time in school. But inclusiveness in classroom practices is a complex matter, and also needs to take into account deep-seated mindsets and perceptions about the capacities for learning among different groups of students. As found in a recent RISE study in Vietnam, teachers held different implicit beliefs about the capacities of ethnic majority and ethnic minority children. It’s important to remember that girls will make up about half of almost any group, and girls in marginalised communities are likely to be at risk for even greater exclusion. So, for example, practices that ensure inclusion for marginalised students are likely to help marginalised girls.

To give girls, boys, and the adults they will grow up to be the best shot at healthy, productive, fulfilling lives, incremental improvements are not enough; systemic reform to education is needed. This will require making foundational skills for all a national priority, getting girls into school on time and ready to learn, and reforming systems so that curricula and instructional practices are inclusive and aligned to clear learning goals. Reforms like these can bring about the transformation that is needed to give every girl the education she deserves.

Many thanks to the RISE Directorate's Lillie Kilburn for providing input on this blog.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.