Jason Silberstein

Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

Blog

At the recent CIES 2023 Conference, a RISE-organised panel highlighted four practical, collaboratively developed tools for applying systems thinking in education.

There is growing demand for practical ways to apply systems thinking in international education. The RISE Programme and its partners have been working to develop rigorous, research-informed tools to analyse education systems. These tools clarify systems thinking into something you can “do” or “use” to gain concrete insights into how to improve student learning in a particular context.

At the CIES 2023 Conference on 18–22 February in Washington DC, a RISE-organised panel highlighted four of these tools. The blog discusses each tool in turn (including a bonus tool at the end). The tools are roughly ordered by the level of insight they offer, from more granular analysis of how specific parts of an education system are working together within a specific country (i.e., whether the steering wheel connected to the ship’s rudder) up to comparative analysis across countries of which high-level polices to prioritise in order to improve learning (i.e., what direction to steer the ship in).

Here is a summary table of each tool’s purpose and the products that the tool produces, along with a partial list of the organisations and countries where each tool has been put into practice.

| Tool | Purpose | Product | Users/partners | Country coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surveys of Enacted Curriculum (SEC) | Teacher professional development and tracking curriculum implementation (among others) | Heatmap visualisation and quantitative measures of alignment between curriculum, assessment, and teacher instruction |

|

|

| RISE Education Systems Diagnostic | Strategic planning or retrospective policy analysis (for government); programme design (for organisations) | 10-page qualitative narrative diagnosing which components of the education system are not working together as well as they could to deliver learning |

|

|

| Learning Trajectories | Policy prioritisation (national and subnational levels) | Visualisations and policy simulations to understand and plan to address the learning crisis |

|

Global |

| Spotlight Series | Monitoring progress and peer learning (cross-country level) | Comparative analysis of challenges and solutions to low primary school completion and foundational learning |

|

Africa |

| Education Systems Course | Establish systems thinking as a subdiscipline within graduate schools of education | Open-access syllabus and recorded lectures from leading researchers and practitioners |

|

|

A frequent challenge when trying to practically apply systems thinking is interconnectedness: do you have to change everything to get anything done?

My frequent answer is to bring up the idea of alignment between different parts of the system. Systems thinking doesn’t have to always encompass and attempt to interrelate every single element of the system at once. In fact, it can sometimes be more useful to deep-dive into subsystems and how their constituent parts are fitting together (or working at cross purposes).

The Surveys of Enacted Curriculum (SEC) is a methodology to do exactly this for the instructional subsystem. It offers a systematic, quantitative method to explore how well the curriculum, assessments, and teacher instruction are aligned with each other.

The SEC approach has been used for 25 years in the USA. More recently, it has been adapted to developing-country contexts, first by RISE researchers in East Africa and now through a collaboration between RISE, RTI, and the government in Nepal.

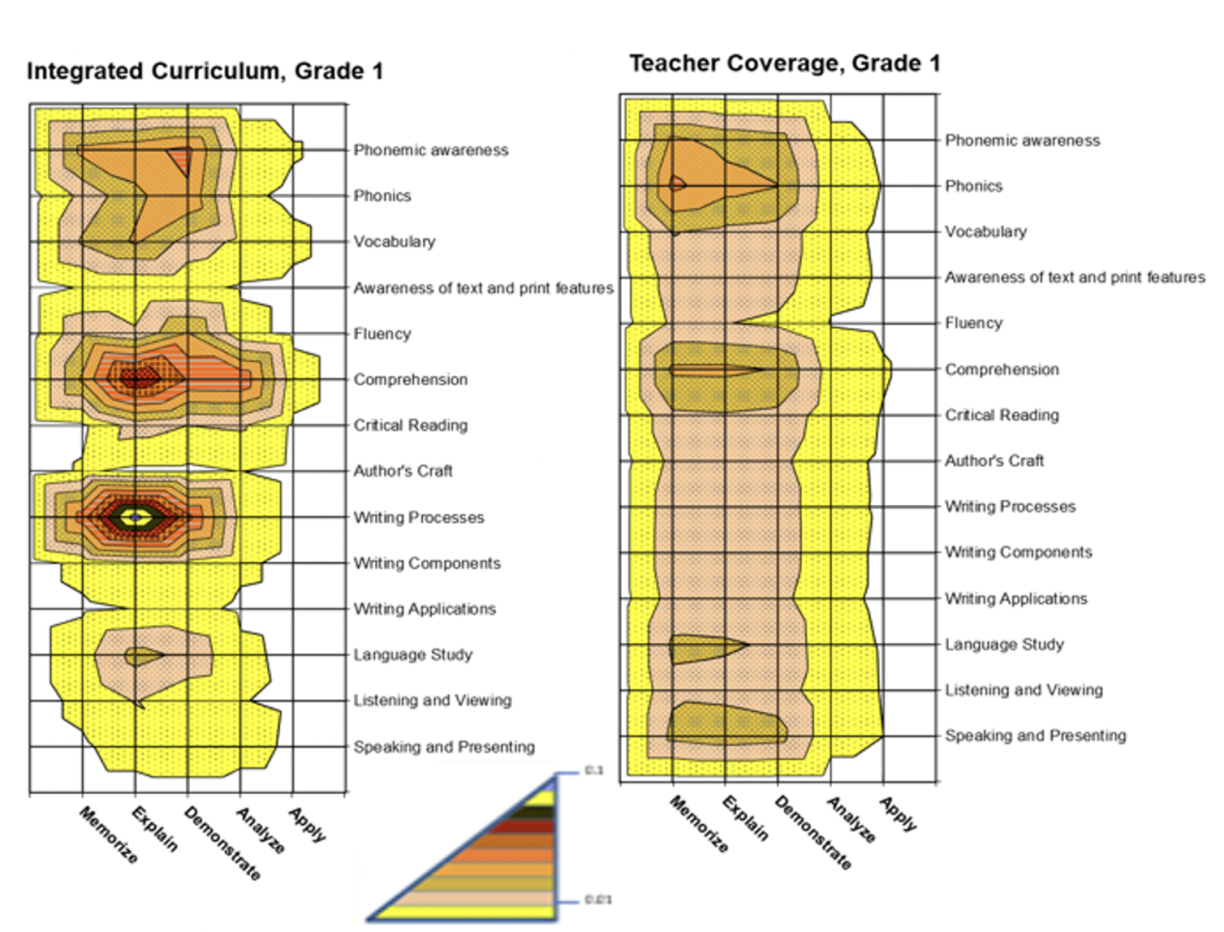

At CIES, Jodie Fonseca of RTI discussed how Nepal recently rolled out a new Grade 1–3 “integrated curriculum”. They recognised the SEC methodology as a way to study how the new curriculum content was being implemented by teachers in practice. It also offered a way to gain insight into how well an adapted Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA)—which was being used for teachers to understand their student’s learning levels—lined up with the curriculum.

The findings are fascinating. For example, the study finds that the new curriculum covers the five basic reading skills (phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, comprehension, and fluency) throughout the early grades of primary school, providing the necessary foundation for subsequent learning.

However, both the curriculum and teacher instruction emphasise low-to-middle levels of cognitive demand. This means that children may not gain the mastery needed for higher-level analysis and application of skills. Furthermore, while the curriculum prioritises specific skills, teachers spread their instruction across topics. The content maps below show this relatively small but still noticeable misalignment between curriculum standards and instruction.

Note: Surveys of Enacted Curriculum study in Nepal, 2021–2022. Visualisations represent 3-dimensional content maps. Instructional topics are on the Y axis, levels of cognitive demand on the X axis, and level of emphasis on the Z axis. Within each component (i.e., curriculum and teachers’ instructional coverage), the levels of emphasis at each topic/cognitive demand intersection point sum to 1 (totalling 100 percent of emphasis).

Source: Atuhurra et al. 2023

The full study has many more content maps and many more findings.

The potential applications of the SEC methodology are many: to study curriculum implementation, to provide feedback loops into teacher professional development, to rationalise the curriculum so that it is in line with student’s current learning levels, to consider the progression of content across grades, and to study the alignment of textbook content, among others. With further studies already underway in Nigeria, SEC is just getting started.

Over the past few years, a team at RISE has been working to convert the RISE systems framework (also known as “the 5x4”) into a practical diagnostic tool to identify system-level constraints on improving children’s learning.

The resulting Diagnostic toolkit (also available in Spanish and Portuguese via SUMMA Laboratorio de Investigación e Innovación en Educación para América Latina y el Caribe) was piloted during 2022 in six countries by six different partner organisations.

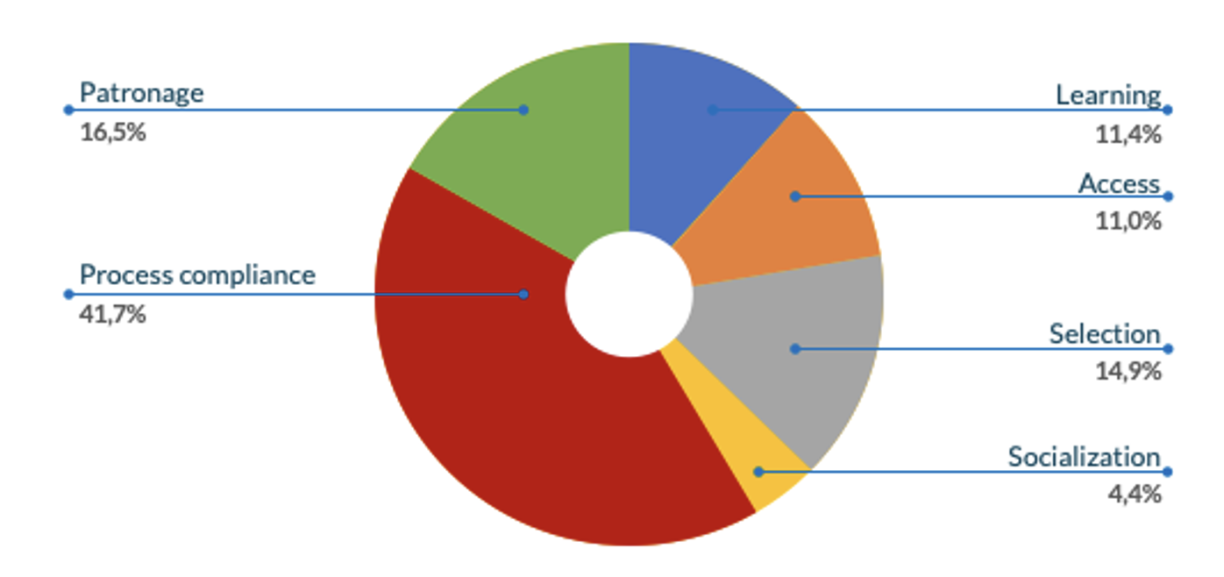

At its core, the Diagnostic offers a process for teams to first develop a qualitative description of the different parts of an education system and then analyse their findings in relation to a detailed template of what the different parts of an education system typically look like under different possible alignments. (For example, what does a system look like when it is pursuing learning goals vs. schooling access goals vs. process compliance vs. patronage?) This allows the teams to diagnose specific misalignments in the education system and to highlight specific system levers that could have an outsized impact on shifting the wider system toward children’s learning.

At CIES, Javier González of SUMMA (a leading education think tank in Latin America) presented the results of the organisation’s pilot of the Diagnostic in Ecuador. Over seven months, through workshops and interviews with 53 participants, the SUMMA team concluded that the Ecuadorean system is predominantly aligned around complying with central administrative requirements, like filling in reports.

The study offers multiple examples of how specific parts of the system have become too tightly aligned around top-down compliance and lost sight of the goal of learning. (It should also be noted that the report discusses how compliance with rules was a positive, or at least logical, response to pre-existing corruption in the system). For example, the report describes management structures that incentivise pedagogical improvement staff and school leaders to focus on administrative oversight and reporting rather than on offering support to teachers.

The findings from this Diagnostic have been published as a working paper by the SUMMA team and summarised in a blog. They have also been discussed in Ecuador by a steering committee with representation from across the government, including the minister of education.

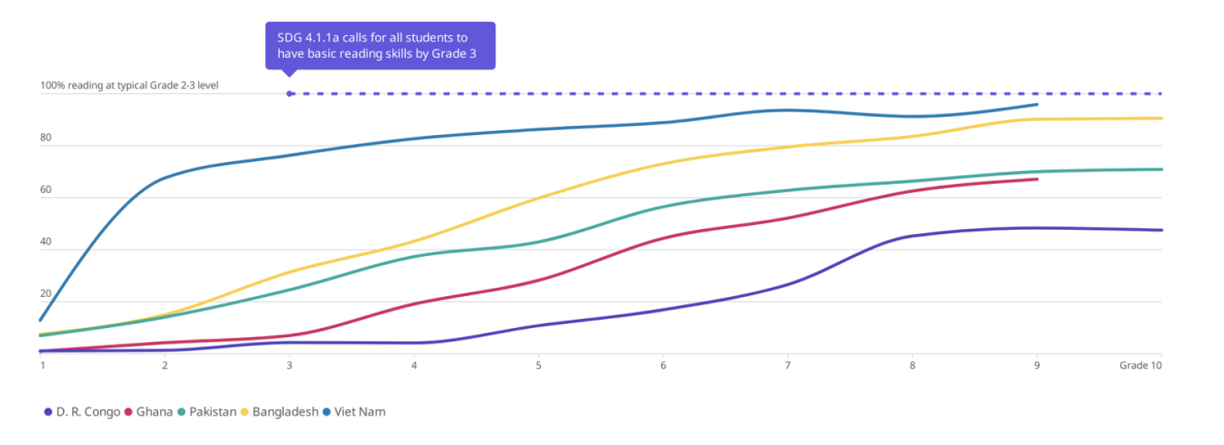

Learning trajectories are a tool for high-level policy prioritisation. They enable users to better understand and visualise the learning crisis and to run simulations that estimate the impact of common policy reform strategies on children’s learning levels.

Perhaps the easiest way to understand learning trajectories is by seeing one:

Source: GEM Report SCOPE website based on analysis of UNICEF MICS6 data as described in Kaffenberger and Silberstein (2022)

This graphic comes from an interactive online tool which RISE and the Global Monitoring Report (GEM-R) have developed as a one-stop-shop for learning trajectories. The online tool allows users to build and analyse their own learning trajectories, explore key policy messages through interactive data visualisations, and run their own policy simulations.

During the CIES panel, RISE researcher Rastee Chaudhry gave a demonstration of the tool’s breadth and depth. In terms of breadth, the tool currently covers 30 countries. It is powered by data from the MICS6 household survey. (Led by a team at UNICEF, the MICS6 education module is among the largest recent surveys of foundational reading and math skills around the world. It is nationally representative for children of ages 7–14.)

In terms of depth, the presentation highlighted a number of key insights from the tool, such as:

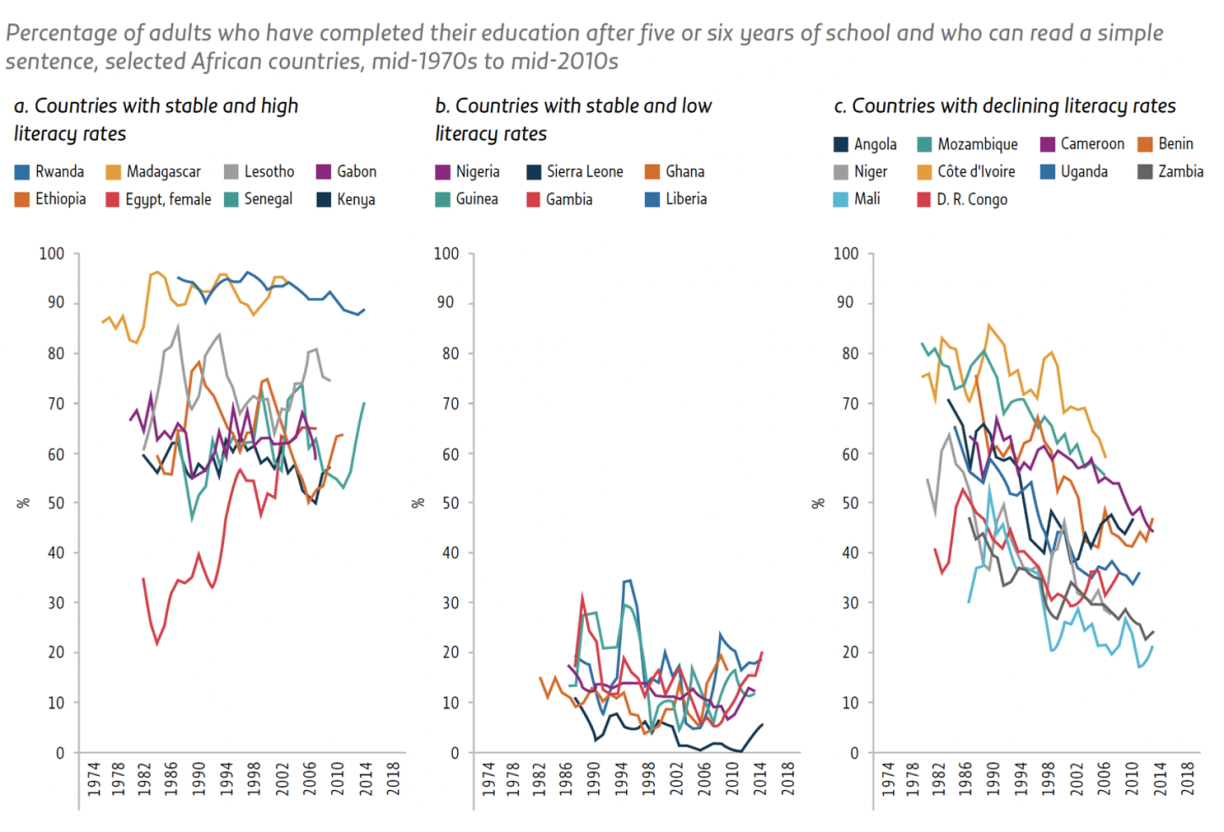

The Spotlight Series is a new initiative from the Global Education Monitoring Report (GEM-R), shining the spotlight on primary school completion and the state of foundational learning in Africa. It is as a tool for comparative analysis of how African countries are progressing against these goals and of the challenges and solutions these countries are encountering.

The Spotlight Series incorporates data from the other interactive databases that the GEM-R maintains (i.e., VIEW on completion rates; WIDE on inequality; PEER on national policies; SCOPE on cross-country progress over time for multiple indicators) and combines these data sources with original research.

Source: UNESCO (2022)

At CIES 2023, Spotlight lead Jo Kiyenje presented on the first of three planned cycles of the Spotlight. This first cycle focused on 12 African countries.

In addition to being an analytical tool, the Spotlight also offers recommendations for high-level policy priorities, both at the system level (e.g., set an explicit foundational learning target and centre it in the national educational vision) and the student level (e.g., one textbook per child, home-language instruction, school meals).

Perhaps most ambitiously, the Spotlight seeks to increase the political salience of foundational learning and help countries learn from each other. It will pursue these goals through the Spotlight’s core partners at the African Union and the Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA).

(For more on the Spotlight Series, check out this podcast with Manos Antoninis, Director of the GEM-R).

The Systems Course did not fit into the CIES panel since it is aimed more at academia than practitioners. However, for those who are interested in incorporating systems thinking into their teaching or training, the Systems Course provides a 10-unit syllabus with an accompanying reading list and recorded lectures from 18 globally recognised scholars and experts. All these resources are open-source and can be repurposed piecemeal or as a whole. With support from RISE, the course was jointly developed by faculty at four universities. It has run as an elective module for two consecutive years at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) in Pakistan, the University of Cape Coast (UCC) in Ghana, and University College London (UCL) in the UK, allowing master’s students to learn collaboratively across three continents.

The RISE Programme will soon formally come to an end. However, these tools will live on, and continue to offer the education sector empirically backed ways to apply systems thinking in practice.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.