Yue-Yi Hwa

Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

Blog

What do buying vegetables and taking exams have in common?

Answer: cheating.

When incentive and opportunity align, some degree of cheating is likely to result. That is, if we can feasibly manipulate a system of exchange, and if we stand to gain by doing so, then some of us will choose to cheat. Like the supermarket customers who choose the ‘carrots’ button on the self-service checkout machine when they’re actually loading much pricier avocados onto the weighing scale.

Yet incentive and opportunity aren’t usually enough to make cheating so widespread that the system loses its meaning. This is partly because most people also need a third ingredient: justification. Cheating strays into the realm of immorality, so most of us will only cheat if we can tell ourselves a story to lighten the weight of the transgression. One such story could be, ‘The system is unfair.’ Most people would be more comfortable under-paying for vegetables at a multinational supermarket chain than at a makeshift stall set up by a toothy child in their front garden.

Another story—giving one of the most compelling justifications—is, ‘Everyone else does it.’ If cheating is seen as the norm, then this norm can become self-perpetuating, even among people who shun dishonesty in most areas of their life. If you’re at a self-checkout with your friends and they’re all weighing their avocados as carrots, then you might feel uncomfortably self-conscious if you tried to pay full price.

Unfortunately, student assessment seems to be an area where incentive, opportunity, and justification are often oriented toward cheating, at least in certain contexts. Exam cheating scandals have been uncovered in the UK’s storied Eton College and among wealthy and prominent US families.

Also, four new analyses of test score data in Indonesia and India have found patterns suggestive of substantial efforts to manipulate assessment results:

Here’s an example of how extensive cheating can be: Berkhout and her co-authors found that one-third of Indonesian junior secondary schools had suspicious answering patterns in the 2015 national exam. When these schools switched to a more secure mode of testing, their average exam scores dropped by 27 points (on a 100-point scale).

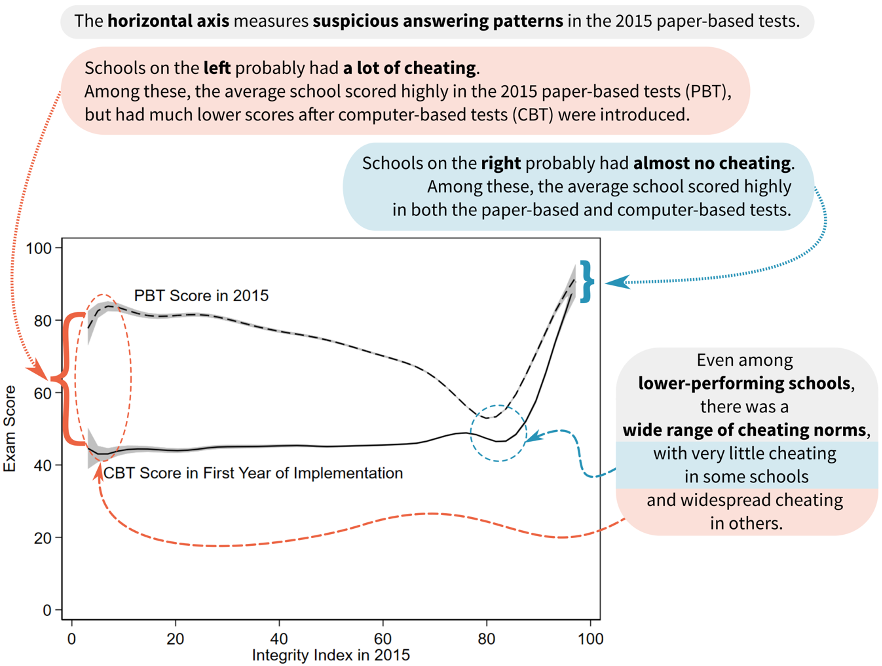

This doesn’t mean that all students, teachers, and schools were cheating. As shown in Figure 1, there was a lot of variation whether or not schools cheated. But it does mean that these was a widespread norm of cheating—to the point where the national exam system had lost a lot of its meaning. Without rich contextual knowledge or careful statistical analysis, it was hard to tell whether a high score in the 2015 exam was due to learning or to cheating.

Source: Berkhout et al. (2020), Figure 3; with added annotations

Fortunately, these new papers on India and Indonesia also point toward three (and a half) ideas for how to reduce cheating in tests.

One way to reduce cheating is by reducing the incentive to cheat. The lower the stakes of a test, the more likely it is that the test will yield accurate results. If the only standardised assessment data in an education system comes from a high-stakes test—whether those stakes affect students, teachers, or schools—then it may be worth conducting a separate low-stakes assessment to get an accurate picture of student learning.

One example of such a low-stakes assessment is the non-governmental, volunteer-administered Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) in India. Unlike teachers who have skin in the game, the volunteers who administer ASER assessments in households don’t have any incentive to cheat. As Johnson and Parrado found in their new analysis, ASER data appear to be far more reliable than data from the government-administered National Achievement Survey (NAS).

Other examples of such low-stakes national tests that don’t affect individual students or schools but give useful system-level information include long-running National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in the US, or the numerous sample-based assessments conducted by the Finnish Education Evaluation Centre.

A caveat: even if a test formally has low stakes, people might still try to cheat on it. The Indian NAS data that Johnson and Parrado analysed were, on the surface, similar to the American NAEP data. Both are nationally representative sample-based surveys that are meant to assess the overall health of the education system rather than individual student performance. Yet there were many indications that the NAS data were artificially inflated. The reasons for this inflation are beyond the scope of their study, but possibilities include informal reputational incentives, pressure from higher administrative tiers, or distorted test-taking norms such that many people are used to cheating on any official test that comes their way (which I discuss further under Idea #3).

Besides trying to tweak the incentives associated with a test, administrators can also try to minimise the opportunity to cheat.

In 2016 and 2017, the annual statewide census of student achievement in Madhya Pradesh was administered in three different formats:

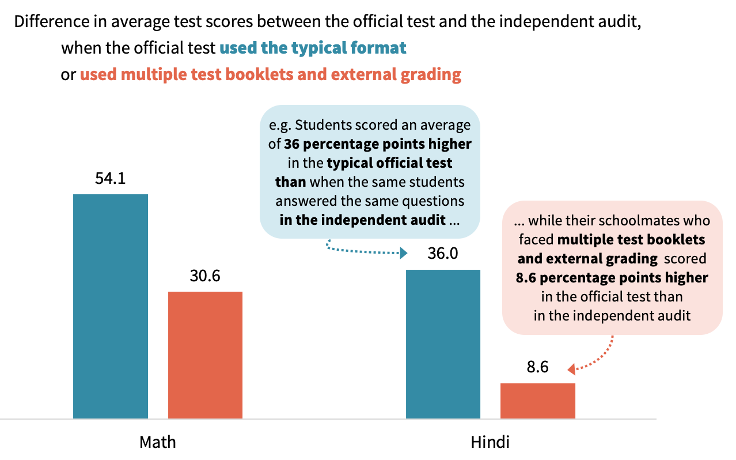

The modified test formats, with multiple booklets and external grading, were intended to reduce test score manipulation. According to Singh’s (2020) analysis, they appear to have succeeded, at least to some degree. When compared to the independently proctored re-test of the same children using the same test items, scores from the Grade 8 students who faced multiple test booklets and external grading were much less inflated than the scores of their Grade 6 and 7 peers in the same schools, as shown in Figure 2.

Notes: generated from student-level estimates with school fixed-effects in Singh (2020), Table 3. For both subjects, the ‘multiple test booklets and external grading’ group comprises students in Grade 8. For math, the ‘typical format’ group comprises students in Grades 6 and 7; whereas for Hindi it only includes Grade 7 students.

One specific method for reducing the opportunity to collude on tests is administering the tests using computers or tablets. Both Berkhout and her co-authors’ (2020) study in Indonesia and Singh’s (2020) study in Andhra Pradesh found that electronic devices made it harder to manipulate test scores.

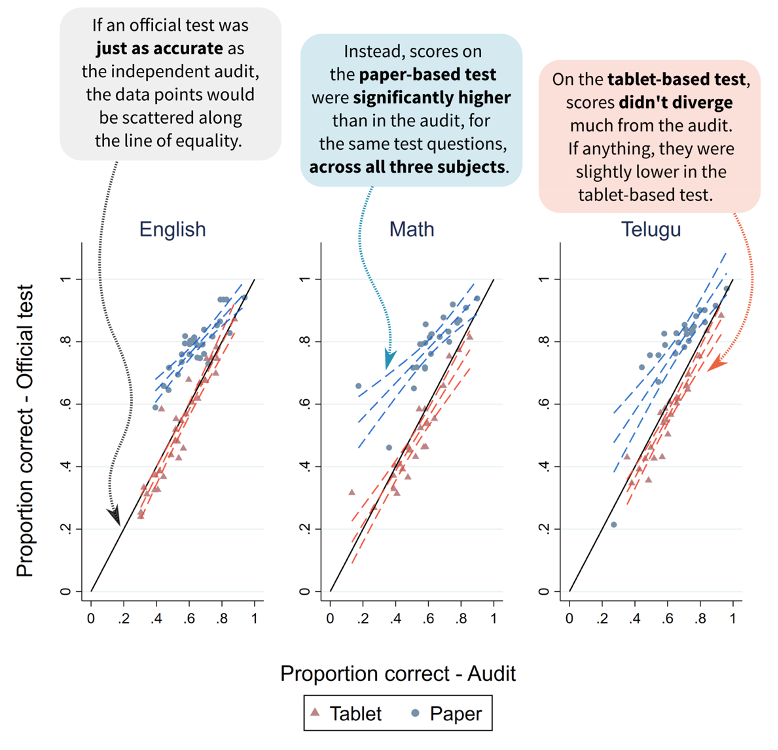

As shown in Figure 3, Singh’s Andhra Pradesh analysis found that the proportion of students who correctly answered a given question on the paper-based test was significantly higher than the proportion who correctly answered the exact same question on the independent audit, across all three assessed subjects. In contrast, the results of the tablet-based test closely follow the results of the independent audit. If anything, students performed slightly worse on the tablet-based test, perhaps because they were less familiar with this mode of assessment.

Notes: Each data point represents a single test item. From Singh (2020), Figure 6, panel (b); with added annotations

Administering tests on electronic devices rather than on paper can make it harder to cheat in a few different ways. In Andhra Pradesh, tablets were an efficient delivery mode for the multiple test booklets and external grading discussed in the previous section. Additionally, the tablets were managed and transported to schools by cluster-level authorities, which meant that every test was externally proctored (Singh, 2020). In Indonesia, the tests were administered on school-based computers, but each student’s set of questions was randomly drawn from a very large item bank on a central server. In addition to preventing students from copying answers, this prevented teachers from anticipating questions and coaching their students accordingly (Berkhout et al., 2020).

Besides eliminating an avenue for manipulation, the automatic grading and recording of electronically administered tests can also lighten teachers’ paperwork burden. Still, as with most education policy decisions, there are trade-offs. Maintaining and preventing theft of electronic devices may prove as big a burden to schools as grading exams by hand would be.

It’s also important to note that computers cannot magically overcome the prior technical challenge of designing high-quality test items. Test items that don’t actually assess the targeted knowledge will yield inaccurate results—whether their medium of delivery is easy to manipulate or ironclad.

Besides reducing the incentives and opportunities to cheat, another point of attack would be the justification for cheating. Test scores are also shaped by the practices of those on the receiving end, whether students, families, teachers, school leaders, or administrators. All of these actors have various and sometimes competing priorities. These priorities, in turn, can shape local test-taking norms.

In some settings, test-taking norms have turned cheating into an acceptable—or even desirable—practice. For example, one teacher interviewed in Madhya Pradesh suggested that there are reputational incentives for self-serving inflation of test scores at all levels:

On paper, all achievement is very good, all students are in A Grade. […] If we say that all of these students, whom we have shown to be A grade, are actually only at C grade level, then there will be someone here from the administration with a stick asking why this is the case. […] We send A grade results, the Jan Shikha Kendra compares our result and claims accolades that the cluster is doing so well, he sends it to the BRC, who sends it to district-level officials and then finally when the state-level officials look at this on the online portal, they think the school is functioning very well (Singh, 2020, p. 12).

Another teacher suggested that test-score manipulation is normalised, and manifests equally in top-down directives and playground chatter:

[…] we are told that we should not fail the children till class 8. So even if the students aren’t coming to school they are passed. There is one girl who is always absent but confidently says she will pass the exam by copying from others (Singh, 2020, p. 48)

However, even if cheating norms may be widespread, they can still change. In their analysis of Indonesian junior secondary exam data, Berkhout et al. (2020) found within-district spillovers in test-taking integrity as increasing numbers of schools in the district opted into the switch from paper-based to computer-based testing. Even if a school continued to administer paper-based tests, both its test scores and its incidence of suspicious answering patterns declined significantly (on average) once all its neighbouring schools had opted into computer-based testing.

There are two possible mechanisms for these spillover effects. The first is a reduction in the opportunity to cheat for the schools that continued to use paper-based testing. One strategy for cheating was obtaining and circulating the answers to the test before it was administered. The larger the network of potential beneficiaries, the more likely is that these answer sheets will be clandestinely circulated. But teachers and students facing the computer-based test (with its large bank of randomly selected test items) had little to gain from these answer sheets. So as computer-based testing expanded, opportunities for answer-sheet collusion shrank.

The other possible mechanism required active effort from the teachers whose schools had adopted computer-based testing. As Berkhout explains in a blog summarising their analysis:

… teachers from CBT schools might be stricter when proctoring the exams of schools that still take the paper-based exam, to which they are assigned by the district government. (The national exam proctoring procedure is that teachers never proctor students from the school in which they teach.) If their students cannot cheat, to ensure a fair competition, they might also prevent cheating in schools that conduct paper-based exams.

Strikingly, this mechanism also entails a combination of incentive (ensuring that paper-based schools don’t have an advantage), opportunity (proctoring exams in other schools), and justification (favouring fair competition)—but oriented against the old cheating norm. The more schools in a district switched to computer-based testing, the more the scales tipped in favour of test-taking integrity, thus generating new norms.

Here’s to new norms, better information, and fairer competition—whether by closing off channels for cheating; penalising leaders who pressure their subordinates into inflating test results; or (most importantly) giving all children meaningful opportunities for cultivating their academic growth.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.