Zainab Qureshi

Harvard Kennedy School

Blog

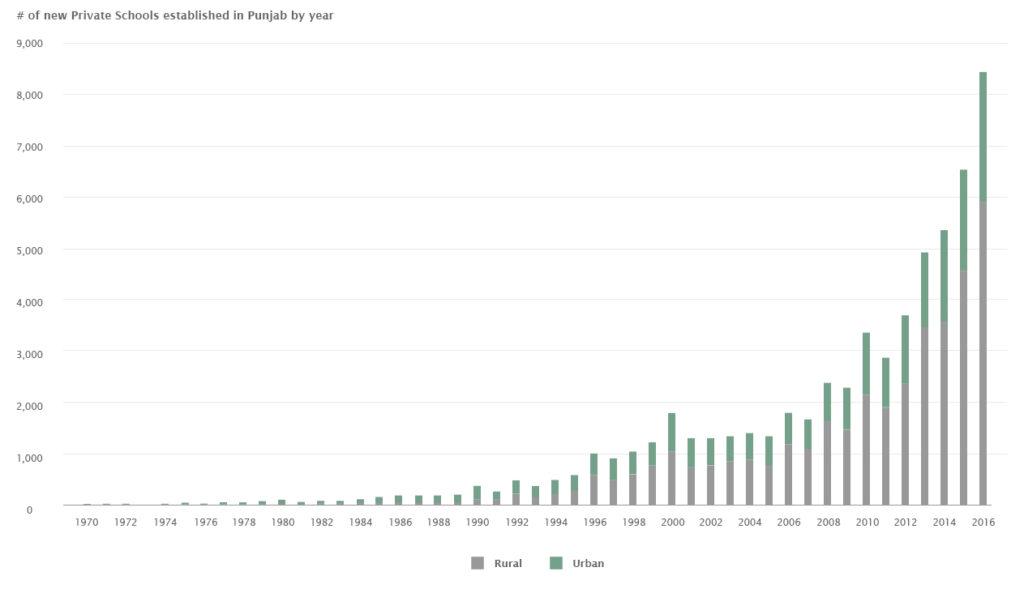

Consider that of the 47.5 million school going children in Pakistan, 42% attend private schools. Of the 317,323 schools in the country, 38% are private. From 1990 to 2016, the number of low-cost private schools in Punjab alone increased dramatically from 32,000 to 66,000. Interestingly, the majority of new private schools opened up in rural areas.

Source: Programme Monitoring & Implementation Unit

In 2008, the Learning and Educational Achievements in Pakistan Schools (LEAPS) research program reported that 40% of the private schools they surveyed in Punjab charged a monthly tuition fee of less than PKR 400, 34% charged between PKR 400-600, 15% between PKR 600- 800 and only 11% more than PKR 800. If the line for low-cost is drawn at a tuition fee of PKR 800 per month, that means 89% of private schools are extremely low-cost, catering to the bottom of the pyramid.

These figures should put the myth that private schools in Pakistan are for the elite to rest. Private schools are not only providing access to schooling but, going by average student performance, are doing a better job at it, too. They are also the single largest employer of women across Pakistan, as an estimated 900,000 women work there as teachers.

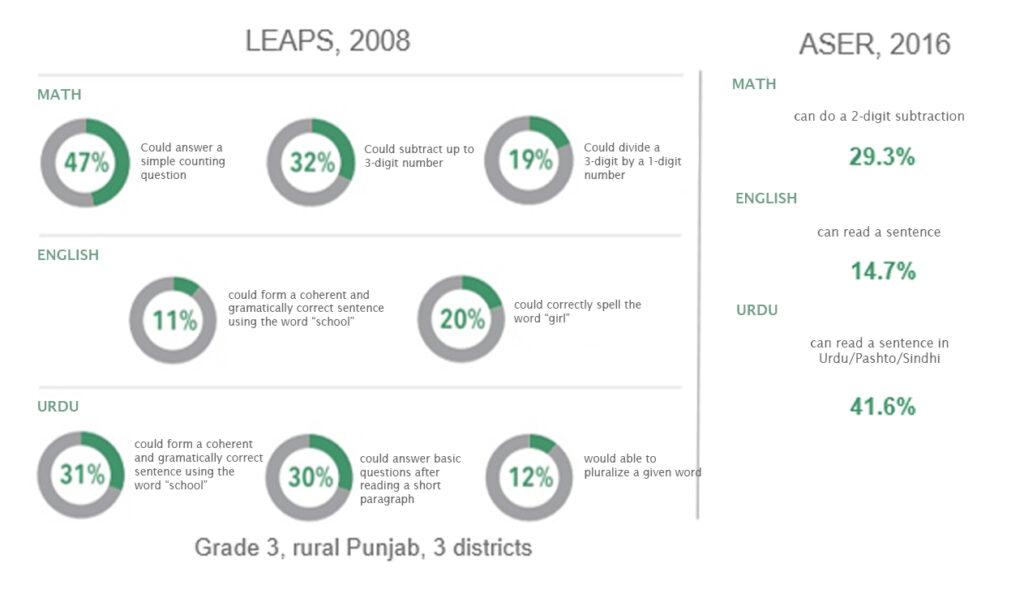

While research shows that private schools have consistently out-performed public schools in terms of student test scores, absolute learning levels in Pakistan remain shockingly low. When data on third grade test scores in Urdu, English, and Math from the LEAPS study in 2008 is compared to the nationwide ASER survey conducted in 2016, it becomes evident that student performance has not budged in nearly a decade. Both tests indicate that a student who drops out in Grade 3 is very likely to be functionally illiterate.

Source: Learning and Educational Achievements in Pakistan Schools (LEAPS) and ASER

Despite poor results overall, LEAPS data shows that private school children perform better than their public-school peers. The median percentage of correct answers given by public school children in Math, English and Urdu range between 25 and 35%. For private school children the range of median scores for the same subjects is between 40 and 50%. The gap in learning outcomes between students in private and public schools is between 8 and 18 times larger than the gap between students from rich and poor socioeconomic backgrounds. This does not mean that every private school outperforms every public school, but, on average, private schools are outperforming public schools by significant margins.

The government of Pakistan has been cognizant of the learning crisis and has actively tried to tackle it. While public spending on education still lags other emerging markets, it has still been on the rise since the passing of the 18th Amendment. Between 2000 and 2015, 69 education policy reforms were passed nationally and in Punjab, far more than in most low-income countries. However, student learning outcomes did not budge. We hypothesize that one of the reasons for this is that each reform has unintended consequences, and the effects of one may actually neutralize the effects of another, resulting in net zero impact on learning outcomes.

We also theorize that the dominant approach to education reform interventions has not been holistic. Traditionally, we have seen an ‘input augmentation’ approach to improve education: pick one input that seems important for the education production function, such as teacher training or textbooks or infrastructure, test to see if it helps improve learning outcomes, and scale if successful. But how do you decide which specific input to pick? What if it works differently in different contexts?

Instead, the LEAPS team uses an alternate approach that flips the question to the following: What obstacles are holding schools back from performing better, and what happens if we alleviate them? We understand that schools do not operate in a vacuum but are embedded in a dynamic ecosystem inhabited by various stakeholders, each of whom has to be involved effectively in order to make schooling work. LEAPS research has tested this ‘systems approach’ experimentally with both the public and private sectors in Punjab, and offers some valuable insights. The core pieces discussed below include:

Premise: This particular piece of research tests the hypothesis that schools want to improve and innovate but are constrained by lack of resources. Where public schools usually have limited access and/or independence to spend resources to address their needs, private school owners are limited by their revenues.

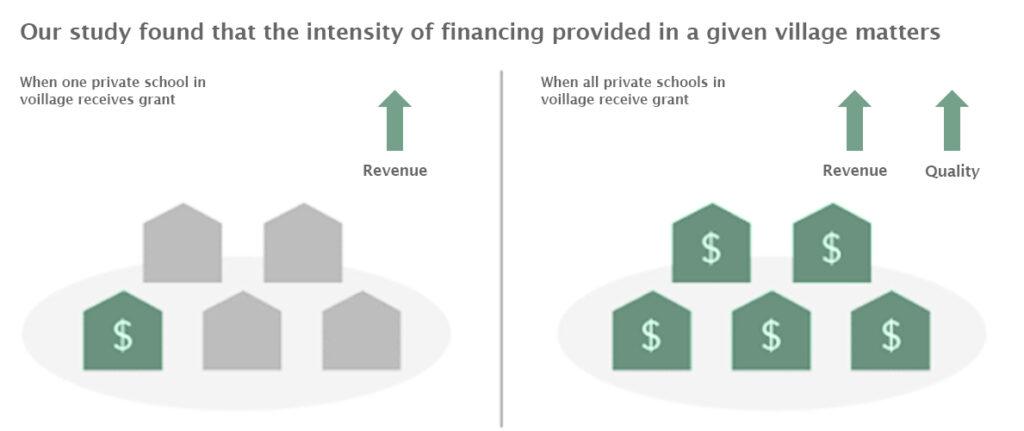

Approach: We conducted an experiment in which we offered 342 private schools in 189 villages an unconditional grant of $500. To explore whether schools react differently when other schools also receive the grant, we gave the grant to only one school in some villages (one-financed/ low saturation) while in other villages we gave grants to all private schools (all-financed/ high saturation).

Results: While enrollment (thus revenue) increased by 12% in one-financed villages as opposed to 5% in all-financed schools, tuition fee and test scores only increased in all-financed villages. Tuition increased in all-financed schools because schools signaled to parents that their quality had improved and were able to charge on average 7.9% higher tuition fees the next year. When all schools are financed in a village, the only way for them to compete is by raising quality. All-financed schools were more likely to pay their teachers more and spent on a variety of things while one-financed schools spent more on fixed items and were less likely to increase teacher pay.

The immediate policy implication from this study is that the method of financing matters just as much as the grant money itself. The all-financed model leads to larger total social returns for the entire village compared to the one financed model, where school owners benefit most.

Source: LEAPS

Premise: Village education markets are a very tight knit community. Information flows fast and competitive parents demand better quality. Even public-school outcomes improve.

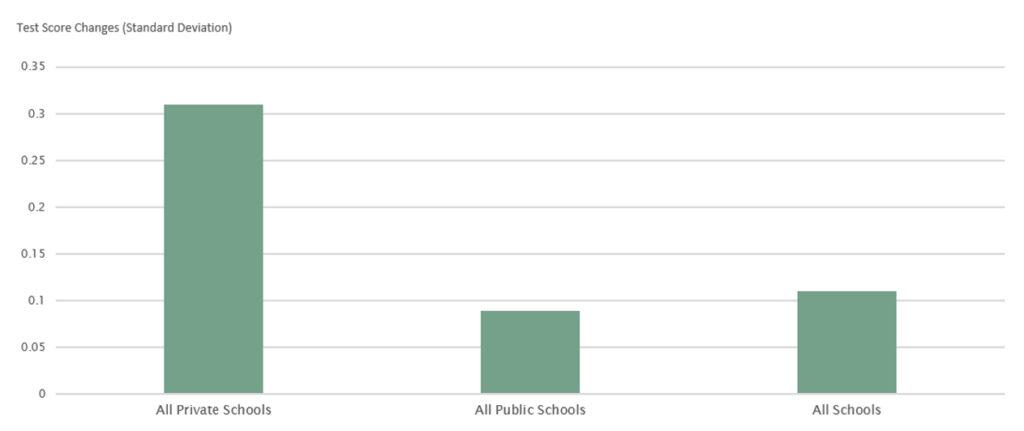

Approach: The LEAPS team conducted a randomized controlled trial in 112 villages across Punjab province. Students were tested and treatment village families were provided report cards with information about their child’s test scores as well as a comparison of the average test scores in the school their child attends versus those in all the different schools in their village.

Results: Treatment villages saw average student test scores increase by about 42% (0.11 Standard Deviations) more than control villages at a cost of $1 per child. Even public schools improved due to parental pressure.

Source: LEAPS

In addition, at least 40 extra unschooled children were enrolled per village at a cost of $22 per child, and private schools lowered their fees by an average of 17% in treatment relative to control villages. The worst-performing schools were more likely to shut down in treatment villages, as their students transferred to other schools.

Policy implication: Easily understandable Information about school quality is a cost-effective and sustainable way of improving quality through parental involvement. An article summarizing this paper can be found here.

Premise: We know that teacher quality matters to student learning and that teachers should ideally be compensated on the basis of their ‘value-add’. However, teacher ‘value-add’ remains an elusive construct. This piece of secondary research tried to deconstruct the concept and offers some important lessons for policy formulation on teacher pay and performance.

Approach: We analyzed a dataset on teachers in Punjab from 2003-2007 to calculate a Teacher Value Added (TVA) score – an estimate of the increase in test score points a student would receive if assigned to a particular teacher.

Results: Teacher quality matters – a 1 Standard Deviation increase in a teacher’s TVA score led to a 0.21 Standard Deviation increase in their students’ test scores. This implies that moving a student from a low-performing teacher to a high-performing teacher can lead to a massive gain, nearly equivalent to one full year of schooling, in learning outcomes.

Interestingly, however, the conventional public-school teacher pay system (that pays based on qualification and number of years of teaching) does not necessarily reward the value a teacher adds. This study found that only 5% of TVA is accounted for by observable characteristics, i.e., teacher content knowledge and experience. Other characteristics such as teacher training or having a bachelor’s degree do not impact TVA significantly. Similarly, lower wages do not necessarily lead to poor teaching. This is evident from the performance of contract teachers (paid 35% less than permanent teachers) hired in the public sector, and from data that shows that private school teachers, who are paid significantly less (about one-fourth) than their public-school peers, perform better.

Policy Implication: Teacher productivity (value-add) impacts student test scores but is not currently always linked to their pay, especially in the public sector. Summary of this paper here.

Premise: LEAPS work spanning over a decade shows that three key failures may be limiting the ability of private schools to innovate, including:

Approach: To tackle each of these constraints, we incorporated findings from multiple studies and are testing a new systems-level solution: Ilm Exchange, a digital education marketplace platform. The idea is to aggregate a large number of schools (public, private and nonprofit) across the country in one place and enable easy access to a large marketplace of educational goods and services, including financial services.

The objective of the platform is to allow for the exchange of:

This is a work in progress but has exciting long-term potential.

This blog has been re-posted with permission from Macro Pakistani.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.