Maryam Akmal

Center for Global Development

Blog

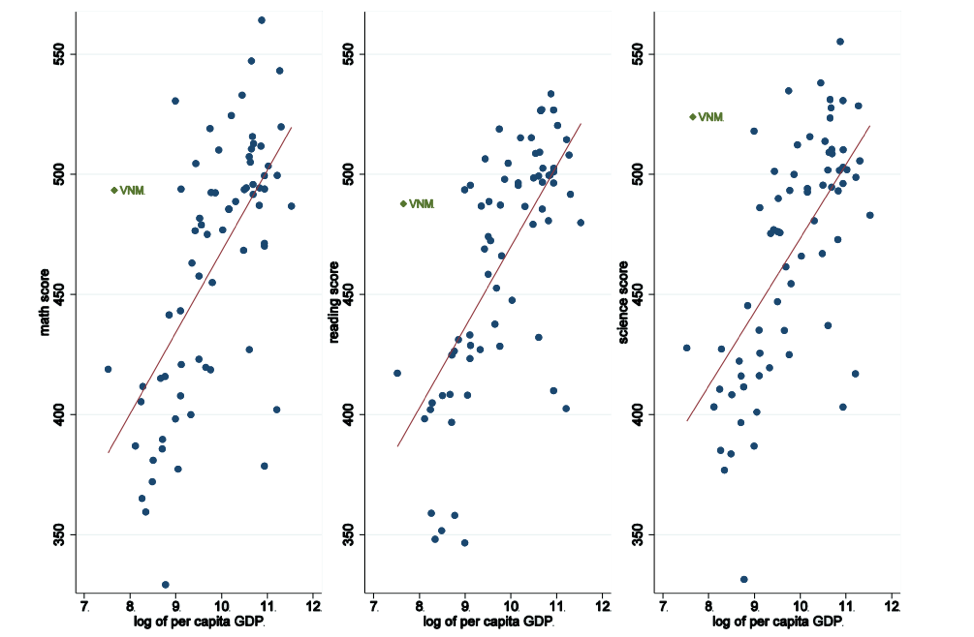

In the last international PISA assessment for math and science, Vietnam outperformed many developed countries, including the UK and the US. Yet Vietnam only has a small fraction of the GDP of these countries. No other low-income country performs at the same level or better than developed countries on an international assessment.

This “Vietnam effect” shows that high education quality is possible even with lower income levels, and appears to reveal revolutionary possibilities. Should other countries with similar income levels, such as Indonesia, be asking themselves: “Why not me?”

Figure 1. PISA test scores versus country income levels, 2015

Source: Dang, H. & Glewwe, P. (2017) Well Begun, but Aiming Higher: A Review of Vietnam’s Education Trends in the Past 20 Years and Emerging Challenges, based on data from PISA and World Bank WDI

The case for Vietnam as an exemplary outlier rests on the measurement of Vietnam’s performance being valid and reliable. Questions have been raised about the validity and reliability of PISA results and whether the high performance of some countries is representative of only a small privileged part of the population. There are two possible concerns: first, the test covers only in-school populations so it leaves out all those children who are not in school, and who may also be more likely to be academically weaker. Second, the PISA sampling may allow some education administrators to select the best performers from “better-off” cities or regions, which could lead to samples that are not representative.

On the first point, not only does Vietnam do exceptionally well on learning outcomes, it also has great results for school enrollment and completed years of schooling. Vietnam has close to universal school enrollment at the primary level and lower secondary levels. Upper secondary enrollment has also seen amazing improvements, tripling from 27 percent in the early 1990s to 70 percent in recent years. In fact, the mean years of schooling of Vietnam’s adult population is higher than would be predicted by its per capita income (Dang & Glewwe, 2017). Therefore, the concern that PISA is not testing a significant proportion of out-of-school children is an issue when drawing comparisons with countries with universal enrollment at the PISA testing age of 15 years, but not a dominant issue.

On the second point, if there are sampling issues where some countries are able to select top performers from “better-off” cities or regions, then these are legitimate concerns that need to be independently investigated. However, the recent RISE paper by Dang & Glewwe (2017) uses alternate data sources to see what learning for Vietnamese children looks like. The paper uses nationally representative high-quality household survey data spanning a period between 1992 and 2014 combined with national grade 5 assessment data. Pulling together all the different data sources and analyzing the results still paints a promising picture of the learning outcomes for Vietnamese children. While these national databases do not allow for cross-country comparisons, they paint a clear upward trend for learning in the country. For math, test scores for grade 5 students jumped 0.40 standard deviations between 2001-2007. For Vietnamese language test, the jump was 0.22 standard deviations. These are huge jumps for a short span of 6 years, particularly compared to countries like India and Indonesia where indications are that scores have been stagnant at best.

Vietnam’s strong performance isn’t a mere illusion.

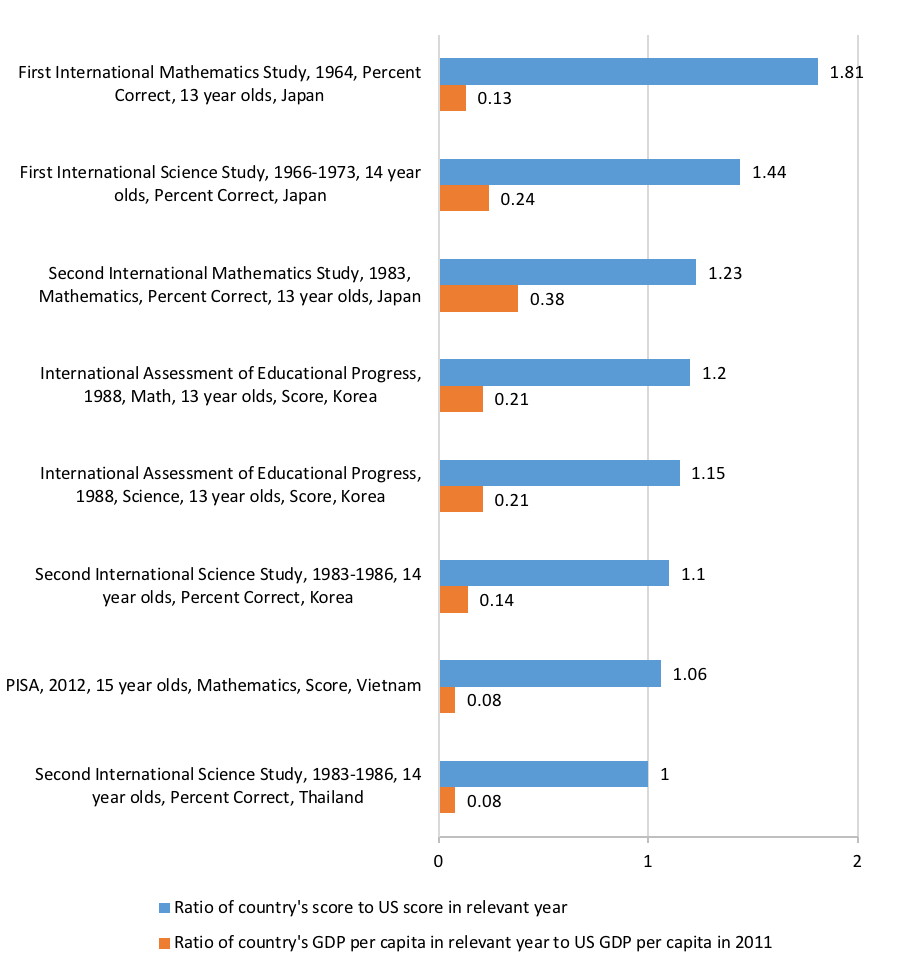

But a second concern is that since Vietnam is the only country in Figure 1 in the “low income/high performance” part of the graph, other countries could draw the conclusion that there is something completely unique about Vietnam. However, Vietnam appearing alone in that part of the space is an artefact of using current scores and GDP per capita. If one looks historically, one sees a number of other countries (albeit perhaps just by bias in the sample of countries for which international assessments took place, we have only East Asian examples) that achieved US levels of performance at levels of GDP per capita that are very low.

For instance, Japan in the early 1960s had only 13 percent of US current income level but already was far ahead of the United States in mathematics performance. In the early 1980s Thailand was still quite poor (had only 8 percent of US current income level, the same as contemporary Vietnam) but had science achievement of 13-year-olds equal to that of the United States.

Figure 2. Many countries have achieved US levels of learning in mathematics and science at very low levels of income

Note: Figure uses the 2011 GDP per capita figure for Vietnam. Figure uses simple average for cases with multiple years.

Figure 2 is potentially good news for two reasons: One, the fact that other countries besides Vietnam have managed to achieve high student learning performance at low levels of income suggests that Vietnam is not a singular experience and hence raises some hope that others can reach similar levels of performance. Two, one reason why the graphs in Figure 1 with just data for 2015 don’t show Japan, Korea, and Thailand as outliers is that they have had very rapid growth and hence have achieved high levels of productivity consistent with high levels of learning achievement. Hence, if Hanushek and Woessmann are right about the huge potential benefits for economic growth of higher learning outputs, then this explains why Vietnam appears in a current cross-section like an outlier—the others who were outliers had massive gains in income.

This still leaves the question of why Vietnam (and not other countries) is such a contemporary outlier? The question is the subject of the RISE Vietnam country research team agenda that is seeking to understand how Vietnam “got it right.”

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.