Joseph Bullough

Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

Blog

In line with this year's theme, “Changing course, transforming education,” we reflect on how far we have come and how far we still have to go.

Today we celebrate International Education Day. It’s a day for recognising the achievements of teachers, students, parents, governments—all those who have been involved in supporting quality education for children and making schools a place where children thrive.

It’s also a time that prompts us to reflect on the vision that we have for every child. A vision where every child learns, develops to the fullest potential of their personality, and is able to direct their own destiny.

This year’s theme for International Education Day—“Changing Course, transforming education”—is inspired by the new UNESCO Futures of Education Report, which paints a picture of what a future where every child learns and succeeds could look like. In light of this, we take a moment to appreciate just how far we have come towards this vision as a community, and reflect on the road ahead, by proposing four steps for realising a future where every child learns.

It’s important to understand how far we have come to give children the promise of an education. Today, many children whose parents did not receive an education can themselves enjoy access to school. The rapid expansion of schooling attainment in low- and middle-income countries is one of the most notable achievements of global development in the last half century. Efforts to support improved transport to schools, books and materials, and trained teachers have simultaneously accompanied this. These great achievements are reminders of what we as a community can do when we set our mind to it.

At the same time, it’s critical to not lose sight of the gravity of the challenge that still stands before us. Today, roughly six out of ten children across low- and middle-income countries (many of whom are in school) are unable to read and understand a simple story by age 10.

In addition, learning levels vary dramatically across low- and middle-income countries, and are low overall, even in countries where spending on education has remained comparatively high. This is because inputs alone, such as education spending, don’t necessarily guarantee learning improvements in the end.

Without basic skills such as reading, writing, and basic arithmetic, students will never be able to reach their potential—and as a community, we will fall far short of our vision to support every child learn and be all they can be.

Foundational literacy and numeracy form an essential first, early building block—a critical prerequisite for all the skills and abilities that children will need to succeed in their lives.

You don’t build a skyscraper by starting with the windows. You build it from the ground up (as Girin Beeharry memorably reminded us). All of the characteristics and skills that we hope children to have mastered, from intercultural competencies; 21st Century skills; digital skills; citizenship; peace education; to environmental education, these start with foundational literacy and numeracy. These priorities can’t be achieved without laying strong foundations (as RISE Programme Director Kirsty Newman points out in her blog “Prioritise!”).

If we do not make learning (and, in particular, foundational learning) the focus of education systems—and measuring progress in learning, and orienting our success around whether children are learning—we cannot be sure whether our education systems are truly working to support children learn.

The COVID-19 pandemic and resulting school closures have made the learning gaps in classrooms more visible than ever. But even before the pandemic, there were significant gaps between children. For example, one (pre-pandemic) RISE study shows that by the time children in India reached grade eight, learning levels ranged from grade two to grade eight across the class (Muralidharan & Singh, forthcoming).

It’s important we don’t fall back into the status quo of assuming that children in the same grade are all at the same level. It’s imperative that we address these gaps by teaching kids where they are, and ensuring that curriculum components (assessment, instruction, standards) are aligned with each other and with children’s needs.

If curriculum progresses at a faster pace than children have been equipped to follow, and if curriculum components are out of line with one another, this can result in children learning very little—and can leave teachers overburdened, frustrated and burned out. Which leads to the fourth point.

It’s undoubtedly important to ensure children have the broad knowledge they need. But doing too much, too fast also has negative consequences for children’s learning.

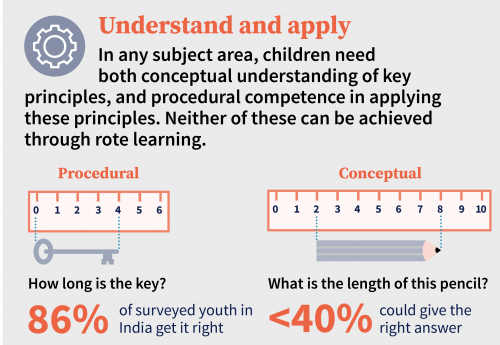

We learn new knowledge best when it builds on prior knowledge, like walking up a flight of stairs. Children need to master foundational skills before they can reach more advanced skills. Because of this, and because it takes time to master concepts and procedures, we need to ensure that teachers are given the time, support and autonomy to help children cultivate deep learning around foundational concepts (not just broad learning).

Overpacking curriculums and making teachers accountable for teaching too much, too fast means that teachers barely have time to scratch the surface of concepts, impairing their ability to cultivate deeper learning with students around these concepts. Ultimately, this can leave children with superficial—or inaccurate—understandings of foundational content, which makes it difficult for them to move to more advanced skills.

Illustration of measuring conceptual and procedural mastery

As the theme for today’s celebrations proposes, let’s join our efforts to change course away from classroom instruction that is misaligned with the needs of students and teachers alike—and to transform education so that all children can build the solid foundations that empower them to soar to great heights.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.