Barbara Bruns

Center for Global Development

Blog

What does it mean for a country to “pivot to learning”? What specific education policies change? How hard is it to implement these – both technically and politically? And above all, how long does it take for student learning actually to improve?

These questions are at the heart of the RISE Programme and are being explored in depth in the six RISE countries. It may be that there are relatively few commonalities, especially across countries in widely different regions and at different levels of economic development.

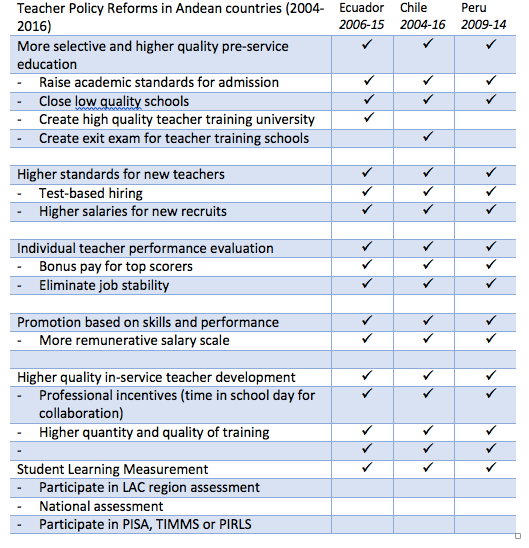

But in Latin America, some commonalities are apparent. Four countries in particular – Chile, Ecuador, Peru, and Mexico – have watched each other strengthen the focus on learning over the past decade and have implemented variations on the same policies (see Table 1). Those that started earlier – Chile, Ecuador, and Peru – have seen significant learning gains on PISA and the Latin American regional assessment.

Ecuador’s turnaround was the most dramatic, and although a unique political context is a major part of the story, our new RISE paper looking closely at “how Ecuador did it” offers some relevant lessons.

First, the country made a clear “pivot to learning.” In the late 1990s, Ecuador was the only South American country which declined to participate in the first regional learning assessment, LLECE, in 1998. But by 2006, with the low quality of education becoming a political issue and inspiring a national referendum, Ecuador signed on to the second regional assessment (SERCE) in that year. When the results showed Ecuador near the bottom in every grade and subject tested, it became a political rallying cry of newly-elected President Rafael Correa that the education system was failing Ecuador’s children and needed deep reform. In 2013, Ecuador launched a census-based national assessment, in 2014 it participated in the third regional learning assessment (TERCE), and in 2016 it joined PISA for Development, to benchmark learning progress internationally. TERCE results in 2014 showed Ecuador’s learning gains were the largest in the region. Starting from no learning measurement, tracking and cross-national benchmarking of learning progress has become central to Ecuador’s education system.

Second, reforms focused on the quality of teaching. In 2009, the core teacher law was re-written, to eliminate teachers’ union control of teacher hiring and Ministry appointments, to raise the bar for teacher quality at entry, and to make teachers more accountable for performance in service. Teacher hiring was now based on competency tests and clear standards; all teachers were subject to performance evaluation at regular intervals that included assessment of their classroom practice; promotions were based on performance evaluations rather than years of service; and dismissal was mandatory after two successive poor evaluations, notwithstanding teachers’ civil service status. These policies were strengthened further in the 2011 Education Law, which took the additional steps of closing low-quality teacher training institutes and raising the minimum university entrance score for teacher training candidates to the same level required for medical school.

Third, reforms were pursued with high continuity over a ten-year period. President Rafael Correa had three successive terms and a single team (a minister succeeded by vice minister) led education over a seven-year period. (In the decade prior to 2008, Ecuador had nine education ministers.) Under technically strong ministers, a cohesive and technocratic implementation team was built for teacher evaluation, student testing, planning, infrastructure management, and other core functions. Ministry technical staff participated in regular sessions with the economist President that left no doubt of his personal strong commitment to an “education revolution.”

Fourth, policies were adopted to speed reform impacts. Most notably, when teachers and school directors resisted the new meritocratic processes for selection of school directors and mandatory competency testing for teachers in-service, the government offered an attractive early retirement incentive. Over 40,000 teachers and directors (including many unwilling to be evaluated) left the sector, making room for younger and better-prepared teachers; this represented a 25 percent turnover of the teaching force in the space of four years (2008-2012). After the house was cleaned, Correa consolidated the support of new teachers with a doubling of salaries. There are two lessons from Ecuador in this. First, part of the reason that teacher policy reforms take a long time to impact student learning outcomes is that they often only affect new hires; mechanisms to accelerate turnover can help. Second, unlike the experience of Indonesia, which doubled teachers’ salaries but saw no impact on learning, Ecuador did it right: set higher standards first and when the ranks are cleaned, raise the incentives.

A final lesson from Ecuador is that the country enjoyed “tailwinds” driving progress that cannot be easily replicated. Ecuador’s starting point in 2006 was a crisis that unified public opinion around the need to reform and a national referendum that codified the public will. President Rafael Correa has been an unusually powerful, as well as divisive, figure in the country’s history. His healthy election margins and high support in opinion polls empowered radical confrontations with the national teachers’ union. Protracted strikes and violent protests in 2007-8 were met with crackdowns and policies to cripple the union’s political and financial power: eliminating the automatic payment of union dues from teacher salaries; making striking teachers subject to immediate dismissal; and naming successive technocratic ministers over union opposition. By 2016, the union was virtually decimated. Not many Presidents in Latin America have dared to take such actions.

The strong and central role that Correa played in the education sector is not without downside, though. Data and public information about the education system have been less freely available than in other Latin American countries, and there has been almost no critical review of education policies and their implementation by local researchers. In Chile, numerous studies have validated the criteria and rubrics used in the teacher evaluation system; neither the Ministry nor local academics have tested this in Ecuador. And a new IDB study – drawing on data the team collected directly in the context of other research – found that the tests used to screen temporary teachers for permanent positions do not predict better teacher performance, in terms of student learning outcomes.* If tests used in teacher hiring and promotion are not meaningfully linked to better teaching, higher standards will not raise system performance. It remains to be seen how new President Lenin Moreno will respond to this and other policies launched by Correa.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Ecuador’s education reform wave coincided with a commodity boom that allowed the country to increase education spending dramatically – from 1 percent of GDP in 2000 to more than 5 percent (of an expanded GDP) in 2014. With virtually no spending constraint, the government was able to build new schools, upgrade schools, and expand enrollments at all levels, while investing in books and materials, a new teacher training university, retirement bonuses, and doubling teacher salaries. There is no doubt that Ecuador designed and implemented major, politically challenging reforms of education over the 2006-2014 period. But there is equally little doubt that the absence of fiscal pressure created a favorable context that very few reformers enjoy.

Ecuador’s education policy choices and results offer a useful window into how “pivoting to learning” and major reforms focused on teaching can substantially transform an education system in the space of one decade. Unique features of Ecuador’s political and economic context over the same period that facilitated reform, but may undermine sustainability, are equally important fodder for reflection.

*If tests used in teacher hiring and promotion are not meaningfully linked to better teaching, higher standards will not raise system performance. It remains to be seen how new President Lenin Moreno will respond to this and other policies launched by Correa.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.