Luis Crouch

RTI International (Emeritus)

Insight Note

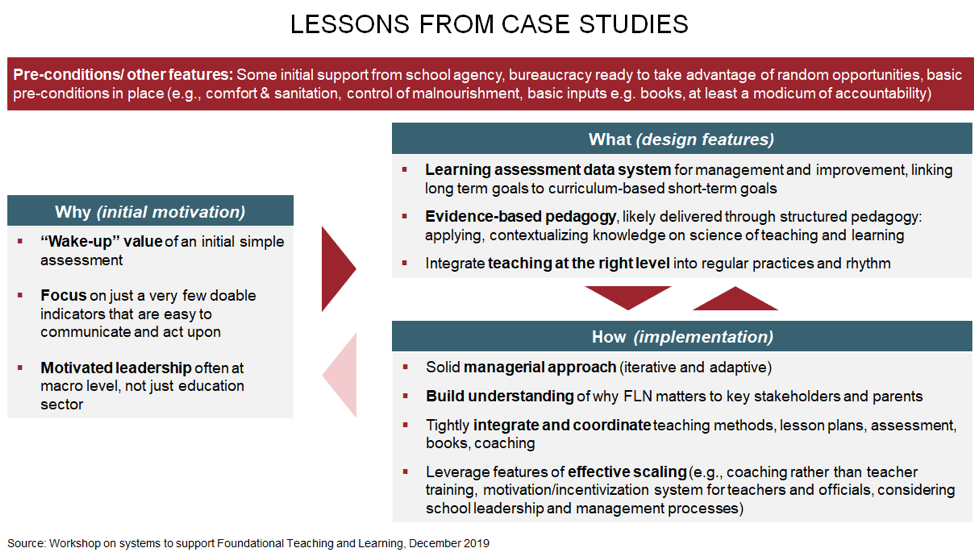

The case studies in this document highlight five tips that may be beneficial to other countries or situations:

As this note was being written in April and May 2020, the Coronavirus pandemic was sweeping the world. Children were out of school. Researchers around the world are now estimating a severe learning gap due to loss of school attendance. While the first priority is getting children back to school safely, the discussion in this note regarding foundational learning is all the more relevant, as it is this kind of learning that is likely most affected.

In recent years, the expansion of education systems has led to unprecedented numbers of children attending school—nearly 90 percent of primary-school-aged children globally are enrolled in school, and in low- and lower-middle-income countries, as a whole, far more than half complete primary school.1 However, there remains a learning crisis globally, and 6 out of 10 children and adolescents are not meeting minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics.2 The scale of this crisis requires bold, transformative changes to education systems. While there have been advances in know-how on specific learning interventions, the challenge now is in moving crucial parts of education systems so that all young people, at a minimum, are literate and numerate by the time they leave primary school.

One reason education systems struggle to address the learning crisis is that the quality of the sub-systems (curricular design and lesson plans, textbook design, assessment tools, and teacher coaching and support) is often low, and in some cases missing altogether. Just as importantly, though, the coherence among these “core” sub-systems is often missing. They are typically overseen by different agencies or units within the same ministry, with varying priorities and varying degrees of success in coordination. Examples of such incoherence:

In the context of these coherence and support challenges, there are several promising examples of how national and sub-national governments in low- and middle-income countries have aligned their sub-systems. These governments are either seeing rapid improvements in learning outcomes or are sustaining learning levels that are better than their peers. In December 2019, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation convened a workshop examining four education systems that have worked to build coherence across their systems, as viewed by “insiders” who played a significant role in carefully studying, designing, or maintaining the systems. The cases are the Sobral municipality in the state of Ceará, Brazil; the state of Puebla, in Mexico; and the countries of Chile and Kenya. In all of these cases, data suggest that the systems have improved performance relatively recently or have historically tended to perform above what one would expect based on context, or generally have a reputation for excellence and innovativeness in their country or region. The workshop was by invitation only, and invitees included individuals from implementing non-profits and NGOs, academia, and development agencies such as the World Bank, USAID, and UNICEF.

The presenters were:

This information note summarises the knowledge shared at the workshop and was produced at the request of key stakeholders at the meeting. It is intended for the benefit of the participants and those who may be designing systems interventions or research, especially around the issue of the “instructional core” and the coherence among the various elements of the instructional core. The note is presented as an informal contribution. It does not pretend to be an original research paper or to possess academic rigor. (No academic bibliographic references are used other than implicitly to the four presentations and background materials developed by the presenters.) The note also does not attempt to evaluate or prescribe or attribute causality. For instance, below, that an intervention may have been prescriptive (or less so) could be causal of the result. But there were other factors as well. All materials presented are based on the presenters’ presentations and related information exchanges unless otherwise noted.

The note was drafted by Luis Crouch, under consultancy to Unbounded Associates, and Kate Anderson of Unbounded Associates. We would like to acknowledge inputs and insights from the presenters, Clio Dintilhac of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Michael Crawford of the World Bank (informal peer review), Manuel Cardoso of UNICEF (informal peer review), Michelle Kaffenberger of the RISE Programme (informal peer review), Mauricio Holanda (consultant, government official, and professor associated with Sobral, key informant), Joe DeStefano and Ben Piper (informal peer reviews) and Ilona Becskehazy (informal peer review), Ed Davis of the Global Partnership for Education, and Melen Hagos of Unbounded Associates.

The note presents informal narratives of the cases derived largely from the presenters’ presentations. Following those narratives, in an Annex that is somewhat detailed but we hope is worth looking at, is an analytical and comparative matrix that compares and explains some of the main features of the three cases (pedagogical methods used, whether there was a “wake-up assessment” that motivated the attention, etc.), using categories requested by the stakeholders at the December workshop. Because that matrix is a little long, a summary is provided here.

As preliminary information, the basic statistics on the three cases (all data refer to most recently available information and are rounded) are:

|

Sobral Municipality, Ceará State, Brazil |

Kenya |

Puebla State, Mexico |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Total population |

209,000 |

49,700,000 |

6,200,000 |

|

Approximate GDP per capita (PPP, most recent) |

US$ 15,300 |

US$ 3,300 |

US$ 11,500 |

|

Number of primary schools |

56 |

38,000 |

4,650 |

|

Number of primary school students |

15,000 |

8,425,000 |

782,767 |

It is worthwhile to point out that while the gains in the cases noted here are impressive, there is still a lot of ground to cover. Even though Puebla is a state in a rather well-off country, compared to most lower-income and lower-middle-income countries, and even though Spanish is an easy language in which to learn to read, Puebla’s children perform at about 0.6 standard deviations below the OECD, or at about the 20th percentile of the OECD distribution, in spite of recent improvements.3 In Sobral, 5th grade children seem to actually perform at somewhere around the 60th percentile of the better-performing 30 countries on the PIRLS.4 Kenyan children, after the intervention shown here, read at about half the fluency expected in the USA.5 So, to varying degrees (though much less so in Sobral given that they seem to be at OECD levels in reading in Grade 5—which makes the case study all the more interesting), there is still work to be done.6 Still, these results are all much better than their own baselines, and also much better than other localities in their own contexts.

To summarise the matrix in the Annex, these were features of the three efforts, though to varying degrees, and are also supported by the emerging literature from, in particular, early-grade literacy efforts. The case studies show five tips that may benefit other countries or situations. The five tips are described more fully below and can be read from the case studies and the long Annex table. They are:

The graphic below summarises.

The graphic makes it clear, from the arrows, that there is a sequencing from the “Why” to the “What”, from the “What” to the “How,” and then also feedback and adaptation, especially from the “How” to the “What.” This creates a virtuous cycle that amplifies the effect over time, maybe a few years, but does not take too long if managed correctly. This was clear from the case studies. This sequencing and iteration are difficult to convey via lists such as the above, and the following, but are key to understanding how the change happened in the three case studies.

The lessons can be provided a bit more at length:

The three governments provide a case-oriented narrative that adds some nuance and chronology to the matrix above. Each case starts with a graphical summary of why the case is and should be of interest.

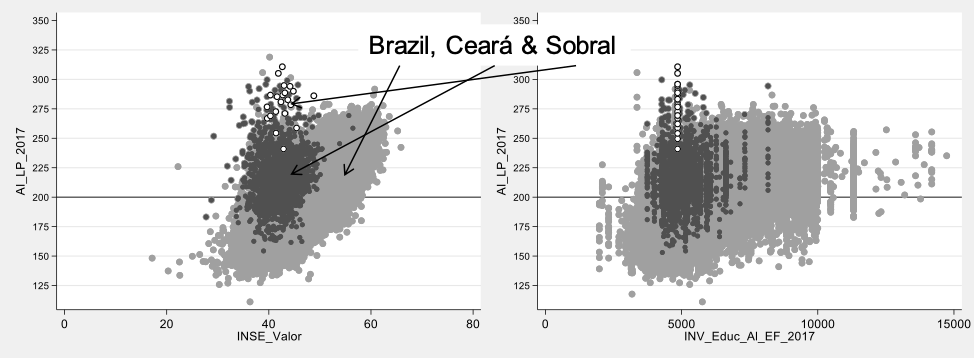

Sobral is a municipality in the state of Ceará, with a population of just over 200,000. Sobral ranks number one out of approximately 5,700 municipalities in Brazil in the national basic education ranking, up from 1,366th place in 2005 as shown in Figure 1 (next page). This rise has come despite high poverty levels, a five-year drought in the region, and a national recession. Sobral’s scores are about 80 percent higher than would be expected given their education expenditure.

The graphic above provides a static picture. The empty white dots are Sobral in the context of Ceara (solid black dots) and Brazil (grey dots).

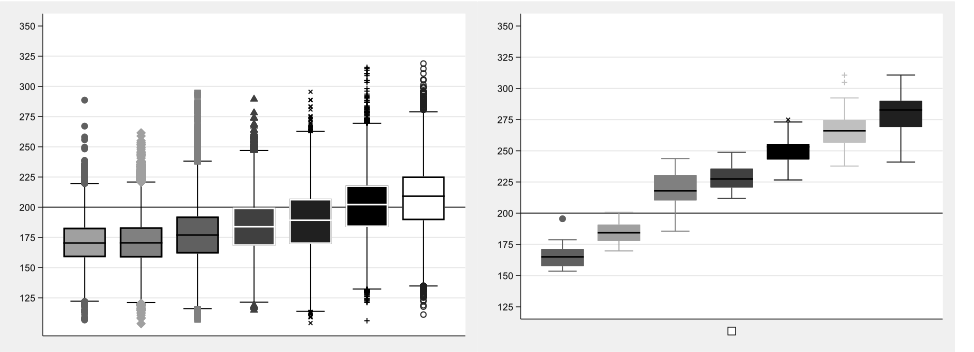

The rapid transformation of Sobral in comparison with the rest of Brazil is noted in Figure 2 (for Grade 5). Sobral is on the right, Brazil as a whole on the left. Both Sobral and Brazil were at the same level in 2005. Since then, Sobral has improved much faster, to about 285 on a 350-point scale, as opposed to 210 for the rest of Brazil (the minimum expected level is 200, in a range of 200 to 275).

The transformation of Sobral’s education system began in 1997 with the election of Cid Gomes as Mayor. Coming from an influential local family, Mayor Gomes first instituted reforms to increase access, improve infrastructure, and mitigate over-age and dropout rates. When these reforms did not have the intended effect on student learning outcomes, Mayor Gomes introduced an additional set of reforms in his second term aimed at literacy, the professionalisation of teachers and staff, decentralisation of non-pedagogic activities, and school autonomy.

The core goals were already set out in 2001, but the specific focus on “alphabetisation at the right age” and the interventions that make the case interesting, and led to the improvements, did not start until 2004. In 2001 the following goals were set:

These reforms started in 2001, but tended to emphasise the student flow issues, in reality. What changed in 2006 was that learning was not improving as markedly as was desired. This led to the introduction of a set of policies that could be summarised as (borrowing liberally and paraphrasing from interviews with Ilona Becskehazy, the analyst and presenter of the Sobral case, at https://tinyurl.com/u7dmoew):

All these factors were integrated into a coherent whole. In addition, the basic principles derived from the “effective schools” literature were applied. These are well known and widely available so are not summarised here.

More recent interventions include fuller and better specification of the curriculum and a focus on reading comprehension, for example, in expository writing, by asking students to a) explain the specific theme and main idea of a passage and explain why that is the case, b) summarise the arguments and connections established between them to support main the thesis, as well as the flaws in the argument, through excerpts that prove them; c) the conclusion of the author of the text on the topic through excerpts that prove it; d) the hypothesis exposed by the author in a specific way; e) the counter-arguments presented by the author in a specific way. (From Ilona Becskehazy at https://tinyurl.com/qsbo72c.)

From a political point of view, it is essential to note the prominence of the Gomes family. Two brothers were both mayors of Sobral and/or governors or congressmen with some focus on education reform for at least 20 years. One brother was Chief of Staff for the other at least once. It is rare to have such championship for an education cause. Countries and development agencies may wish to explore how such championship could be induced.

School autonomy is important in Brazil, so to strike a balance, the terms are negotiated and agreed with the school level, and then the processes are fully monitored and controlled by the central team. In some sense, autonomy is more about operational matters than pedagogical matters, as the pedagogical changes were centralist. Since 2016, Sobral has had a detailed curriculum for language and mathematics. There are annual teaching plans that are detailed down to a weekly basis at the central level, with school representatives participating in their development. Assessment is tightly linked to the lesson plans, as are the learning materials.

Teaching materials for the early years (pre-primary and 1st grade) are provided by an external vendor and are very prescriptive and detailed, including model lessons. Textbooks mainly come from the federal books programme and are complemented by locally produced, structured activities, but the schools (not the teachers) have some room to add materials and activities. Reading books are chosen and acquired centrally.

Though many aspects of the approach are prescriptive, the development was gradual and fairly organic, and came to be accepted, so in the end it may not “feel” all that prescriptive. There is some choice, for example, but the choices may not contain that much difference; they may conform to the same approach. At the same time, the political leadership was able to bring actors along so that the approach does not “feel” that centralist or prescriptive.

It is important to note that many of the reforms have the force of legislation. As elements succeed, they are formalized onto legislation or regulation.

As a last point, in Sobral, the schools in question are no-frills spaces but have all the basic elements for good pedagogy: infrastructure, books, teaching materials, absenteeism control, good and universal free meals in public schools (mandatory in all of Brazil, but better-implemented in Sobral), and playing areas. Having these features is not common in Brazilian schools.

After showing success in Sobral, and with the Gomes family elected to the state government, the Sobral approach is being scaled to all of Ceará.

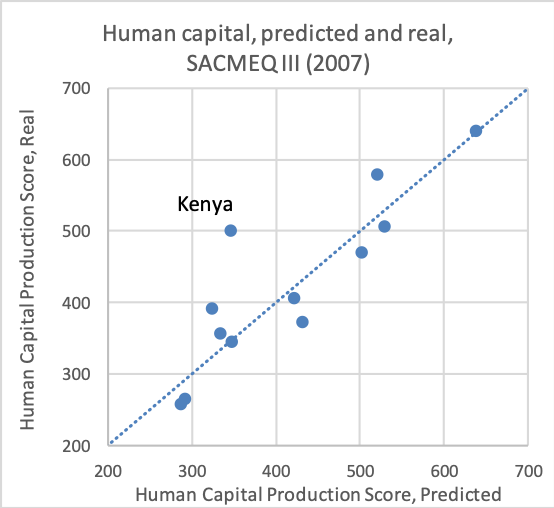

Kenya has a population of almost 50 million and ranks 25th out of 54 African countries in GDP per capita. Kenya’s 2007 SACMEQ scores were much higher scores than other countries in the SACMEQ region, controlling for both expenditure and income per capita (Figure 3 below). Kenya performed about two standard deviations better than the expected value based on expenditure and GDP per capita.

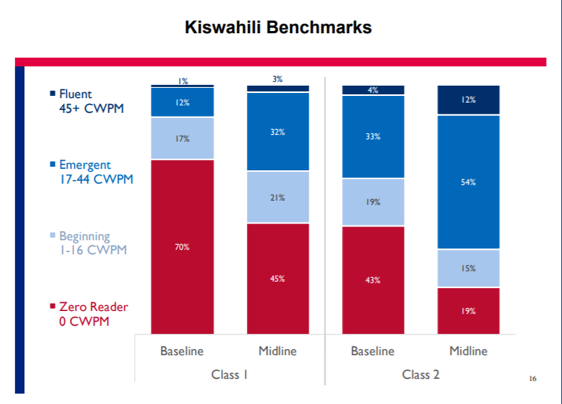

More recently, the Tusome experience in Kenya has produced remarkable results even by mid-line, as noted in Figure 4.

The dark blue color represents the percentage of pupils in either Grade 2 (right two columns) or Grade 1 (first two) reaching mastery at baseline and midline. The red color represents the percentage of students unable to read at all. To those familiar with learning impacts, it will be obvious that these are remarkable changes in just a year or two (but based on much prior refinement in PRIMR).

Since its independence in 1963, Kenya has had six commissions and several taskforces to reform its education system. Between roughly 1995 and 2010-2015, the emphasis of these reforms was on accountability, pay-for-performance, and measurement for accountability. Since 2010-2015, there has been a shifted focus to pedagogy, paying attention to the foundational grades of the education system, and having better books and lesson plans. There were additional reforms that were not necessarily part of these waves, such as reducing the role of double-shifting, moving to full-day schooling, and pro-poor funding.

In 2009-2012, several surveys of student learning, including the Uwezo citizen-led assessments and the baseline of literacy and numeracy through the USAID-funded Primary Math and Reading (PRIMR) pilot reading initiative, found that an alarming proportion of students could not read and write. Given Kenya’s traditional concern with learning, these results were a bit of a wake-up call. Interventions through PRIMR led by the Ministry of Education and RTI resulted in relatively large increases in reading levels, which garnered attention within the ministry and among teachers and motivated key actors to try this approach at full national scale. Beginning in 2014, early pilots were scaled to all public primary schools and 1500 low-cost private schools through Tusome, meaning “let’s read” in Kiswahili.

The Kenya case study is significant in that it is one of the few cases in the literature where the impact at scale-up (Tusome) has been equal to, or better than, the impact of the pilot, and also very quick. However, one should note that that impact would almost certainly not have been possible without the PRIMR pilot.

Since Tusome was to a large extent based on the features and success of PRIMR, it is worthwhile recalling the key lessons and components of PRIMR (borrowing liberally and literally from PRIMR’s final evaluation at https://tinyurl.com/wdzv9jk [and especially circa p. 18]):

Specific implementation features included:

Tusome clarified expectations for implementation of the curriculum and outcomes using national benchmarks for Kiswahili and English, and these expectations were communicated down to the school level. The initiative used functional, simple accountability, and feedback mechanisms to track performance against the benchmarks. These included regular assessments using the Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA). The data collected through the feedback mechanisms were used to inform instructional support at the county level. The effect sizes seen during the PRIMR pilot have been sustained, and in many cases strengthened, in the scale-up of Tusome.

The mid-term evaluation of Tusome (available here: https://tinyurl.com/y3h7wcgz) concludes that the main features responsible for success and suggestions for ongoing and further improvement (borrowing literally and liberally from it, especially pp. 29, 53) were:

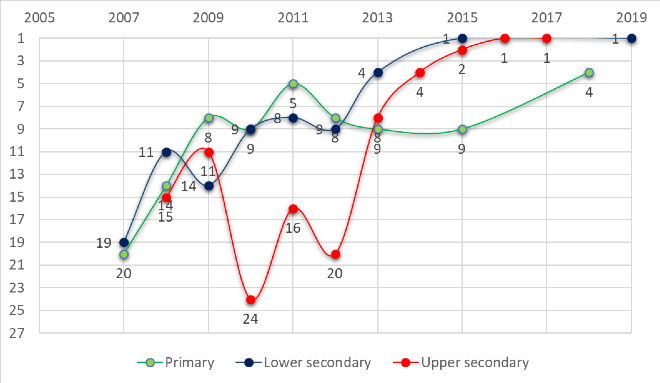

Puebla is the fifth most populous state in Mexico (6.2 million inhabitants; 1.8 million students K-12), and also ranked fifth highest in poverty levels out of 32 states. The state contains 14,000 schools (K-12). It has several native languages in addition to Spanish. In 2015, Puebla became the top state in Mexico at both the lower and upper secondary levels in the national Plan Nacional para la Evaluación de los Aprendizajes (PLANEA) assessment. Since then, Puebla has retained the 1st position in mathematics at the lower secondary levels in 2016, 2017, and 2019, and at the upper secondary level in 2016 and 2017. In language (Spanish), Puebla has ranked between 2nd and 3rd since 2015. When compared internationally, Puebla is one of the fastest improving education sectors participating in PISA. Between 2003 and 2012, the average performance of 15-year-olds increased by the equivalent of almost one full school year.7

This summary takes many points from the presenter’s (Bernardo Naranjo) inputs, including presentations, background writing, and subsequent information exchanges. Because the Puebla case was more iterative, consultative, and complex than the two others highlighted here, it also benefitted from other sources more so than the other cases.8

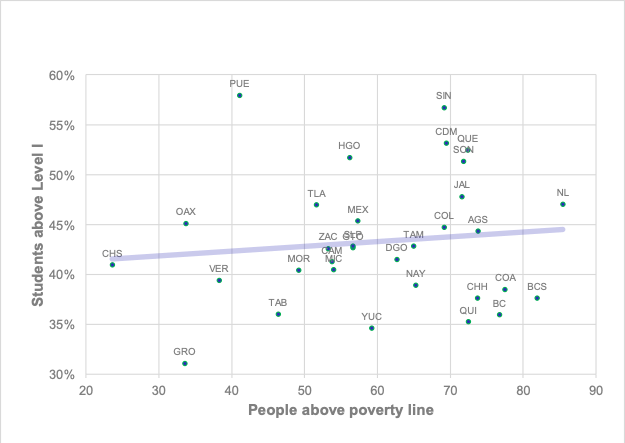

Two graphics explain why the Puebla case is so compelling, and what was achieved in such a short time. The first one shows Puebla to be a major outlier in terms of expected achievement conditional on income. The fact that the regression line is not very strong is immaterial. The point is that Puebla is very much on the edge of the scatter.

Figure 6 below shows academic results over time.

In 2011, a new administration was about to take office in Puebla for the 2011-2017 period. The state Secretary of Public Education (SEPP), a former senator not born in Puebla, immediately started a cultural change. Against a tradition of hiring local people only, he invited people from all over the country to work at the local Ministry.

The Secretary invited several external advisors to help him and requested help from the OECD to write policy recommendations for Puebla (this was the first time the OECD worked at the local level with a Mexican state). Most external advisors had to leave in 2013, when a very large budget cut also made it necessary to reduce staffing in the Ministry. The Puebla intervention survived after its results became known, and it helped that the advisors to that process were based on Puebla.

Initially at the upper secondary level, and by the end of 2013 in the entire K – 12 system, SEPP and “Proyecto Educativo”, a local group of advisors, developed a programme to improve the essential objectives of the education system. The Asistencia, Permanencia, Aprendizaje (APA) (Attendance, Completion, and Learning) model was developed with the following targets, and only three targets:

The SEPP and Proyecto Educativo referred to recommendations by international organizations and national specialists, but the strategy was entirely designed and implemented with local citizens. The model was adapted from an intervention in Ontario, Canada, in the early 2000’s that sought to improve graduation rates and basic learning in English and mathematics.9

The strategies developed to implement the APA model included:

One of the first actions in 2011 was to revive the CEPPEMS (State Commission for Upper Secondary Education), a group that formally integrated all institutions at the upper secondary level. The group met weekly, and technical subgroups formed to work on specific issues (teacher training, information systems, evaluation, dropout prevention, supply-demand analysis). Targeted schools at the upper secondary level kept using the same curriculum and textbooks as the rest of the schools, but received help (teacher training, institutional support) from other schools.

CEPPEMS decided on general strategies, and each subsystem was able to translate them into specific actions, but they all shared their experiences in the group. This allowed structure and creativity at the same time.

Interventions in the primary schools included:

The early-grades primary interventions were coordinated and designed to work together with preschools. Integrating the approach to these two levels was key. At the pre-school level, important steps included:

A certain style of intervention was common to all levels. In training and teacher capacity building, it included:

And in terms of systems management:

The following are lessons learned from the Puebla effort:

The annex includes a table that captures some of the essential elements of the four cases. The table is based on the PowerPoint presentations made by three of the country experts at the December 2019 workshop but also on prior and ensuing discussions regarding each case. We do not present the Chile case here as it covers a complex set of policies developed over a few decades, in a context of already-high performance relative to the rest of Latin America, which has also improved over recent decades. The Chile case also did not describe a pedagogical focus on foundational literacy and numeracy, so a comparison of the Chile case with the other three cases was not possible. Following the summary table are narratives that provide the context and story for each case, after providing data on why the case is worthy of study. In this table, the cases of Sobral and Puebla relate to fairly specific interventions that had a relatively clear beginning and specific development, and the Kenya case relates to a particular intervention with a clear starting point but in a context of historically good performance relative to peers. The table is organised in terms of the "what" (describing the approach or intervention), "why" (why that specific approach and what caused the government to embark upon it), and "how" (how the reforms were accomplished). Each of these three big themes has a set of sub-themes. The case of Puebla had different approaches for various levels; for this note we emphasize the primary or generic (all grades) interventions.

2 http://uis.unesco.org/en/news/6-out-10-children-and-adolescents-are-not-learning-minimum-reading-and-math

3 Approximate, informal but more than back-of-the envelope data only using ENLACE to link to PISA.

4 Even more approximate, informal, but more than back-of-the envelope data using SAEBE data to link to PISA and PIRS.

5 Fluency is used in many efforts as a goal or benchmark that is reasonably easy to explain and measure with reliability. Most experts would agree that the real goal should be comprehension. Some would argue that a good alternative proxy is accuracy of reading. (It is what is being used in UNICEF’s MICS learning module.)

6 We understand that Sobral’s relative performance at the secondary school level is much less noteworthy, which is understandable given that that is not where the efforts were directed.

7 OECD. (2016). Improving School Leadership and Evaluation in Mexico: A State-Level Perspective from Puebla. Paris: OECD. https://www.oecd.org/education/school/Improving-School-Leadership-and-Evaluation-in-Mexico-A-State-level-Perspective-from-Puebla.pdf

8 A working paper by Rafael de Hoyos and Benardo Naranjo on the case, forthcoming in Xaber, an upcoming civil society portal with data and evidence on education in Mexico; personal communication for now. Another useful one is also a study by UNESCO/Mexico titled “Marco de la Política Educativa en el estado de Puebla.” An informative interview with the Secretary of Education for Puebla at the time of the reforms, Patricia Vasquez, can be found at: https://www.inee.edu.mx/origen-recorrido-y-logros-del-modelo-educativo-poblano-asistencia-permanencia-y-aprendizaje/.

9 Some features of the Ontario model generalise what is noted for all three cases in this note; others do not. In common are: a limited number of goals (just three in Ontario, also three in Puebla: hence high focus), a focus on pedagogy rather than general management, province-wide assessment that was relatively low-stakes but thorough, using assessment to assess the system and approach, and help the teachers, rather than for accountability in a narrow sense, assessments that were criterion-reference (see benchmarks used by some of the efforts described in this note), and a province-wide achievement data set. Other features, perhaps more appropriate for a system that was already achieving at levels much higher than those found in Mexico, Brazil, or Kenya, included that the approach was much more teacher-led even in a technical sense, and worked less on teaching technique than on teacher reflection. See https://internationalednews.com/2015/10/28/learning-from-successful-education-reforms-in-ontario/ for a short summary.

Crouch, L. 2020. Systems Implications for Core Instructional Support Lessons from Sobral (Brazil), Puebla (Mexico), and Kenya. RISE Insight Series. 2020/020. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-RI_2020/020