Lant Pritchett

Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford

Blog

Lant Pritchett reviews The Politics and Governance of Basic Education: A Tale of Two South African Provinces, edited by Brian Levy, Irsula Hoadley and Vinothan Naidoo

Brian Levy visited the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford this Thursday to speak about the great new book, The Politics and Governance of Basic Education: A Tale of Two South African Provinces, which he edited along with Robert Cameron, Ursula Hoadley and Vinothan Naidoo.

The book starts from the puzzle of the very low learning achievement of students in South Africa. In the new harmonized learning data used to compute World Bank’s Human Capital Index, South Africa is the worst performer relative to its “expected” value based on its level of income. The book uses the contrasting cases of the Western Cape and Eastern Cape provinces and careful econometric work on student learning outcomes to show that, even after controlling for all the available observable correlates of learning, a child learns much more in the Western Cape than in the Eastern Cape. Moreover, the data also show that, all else equal, a child learns more in Kenya than in the Western Cape.

The analysis builds on Levy’s previous book Working with the Grain, which distinguished between different types of political settlements—how political power is distributed and used—and showed that different politics constrain and shape the available options for organizing and delivering services.

In this new book, that framework is extended. The authors show how the different politics in the provinces (the Western Cape where politics are more competitive; the Eastern Cape where politics are dominated by a single, if fractured, party) interact with different organizational strengths in their bureaucracies (the Western Cape, with its strong and capable bureaucracy in the usual sense; the Eastern Cape, with a more personalized structure), and how these then interact with local school-level governance to produce, sometimes surprising, results.

The detailed case studies of leadership transitions in four matched pairs of schools in the Western and Eastern Cape (in chapters 8 and 9) are revealing. The schools identified as high performing on learning in the Western Cape had a difficult time maintaining that excellence when new principals were chosen, in part because the school governance was weak and hence, performance depended on a charismatic leader. In contrast, the only school of the eight with sustained learning excellence was in Eastern Cape, where the very weakness of the bureaucracy led to strong local school level governance via strong engagement with the parents and community, creating more robust conditions for sustaining excellence.

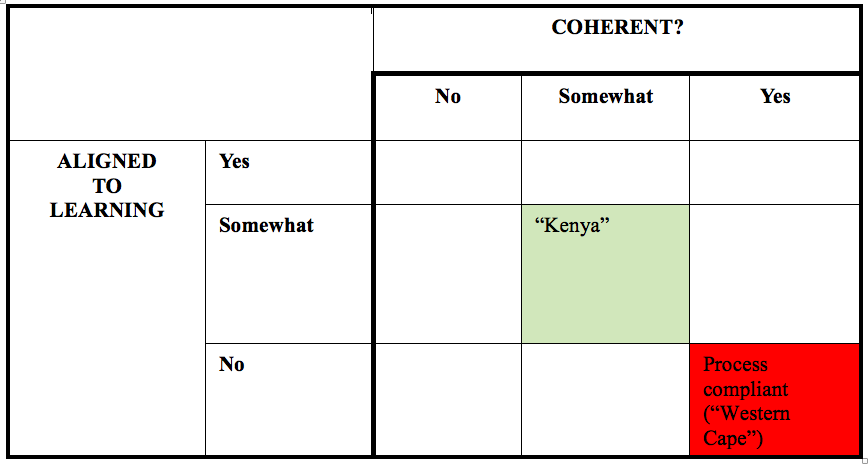

Brian’s discussion of the way forward was particularly illuminating. He includes a useful table (see Figure 1below), classifying whether systems were “coherent” (meaning, having the usual characteristics of a capable Weberian bureaucracy) and aligned around learning. He raised the possibility that there might be a “black hole” of a strong, process compliant, bureaucracies that are not aligned around learning. This would make progress more difficult as it would choke off space for innovation and for the engagement of parents and communities.

Figure 1. Progress on learning can be particularly difficult in systems that are coherent, but not aligned around learning

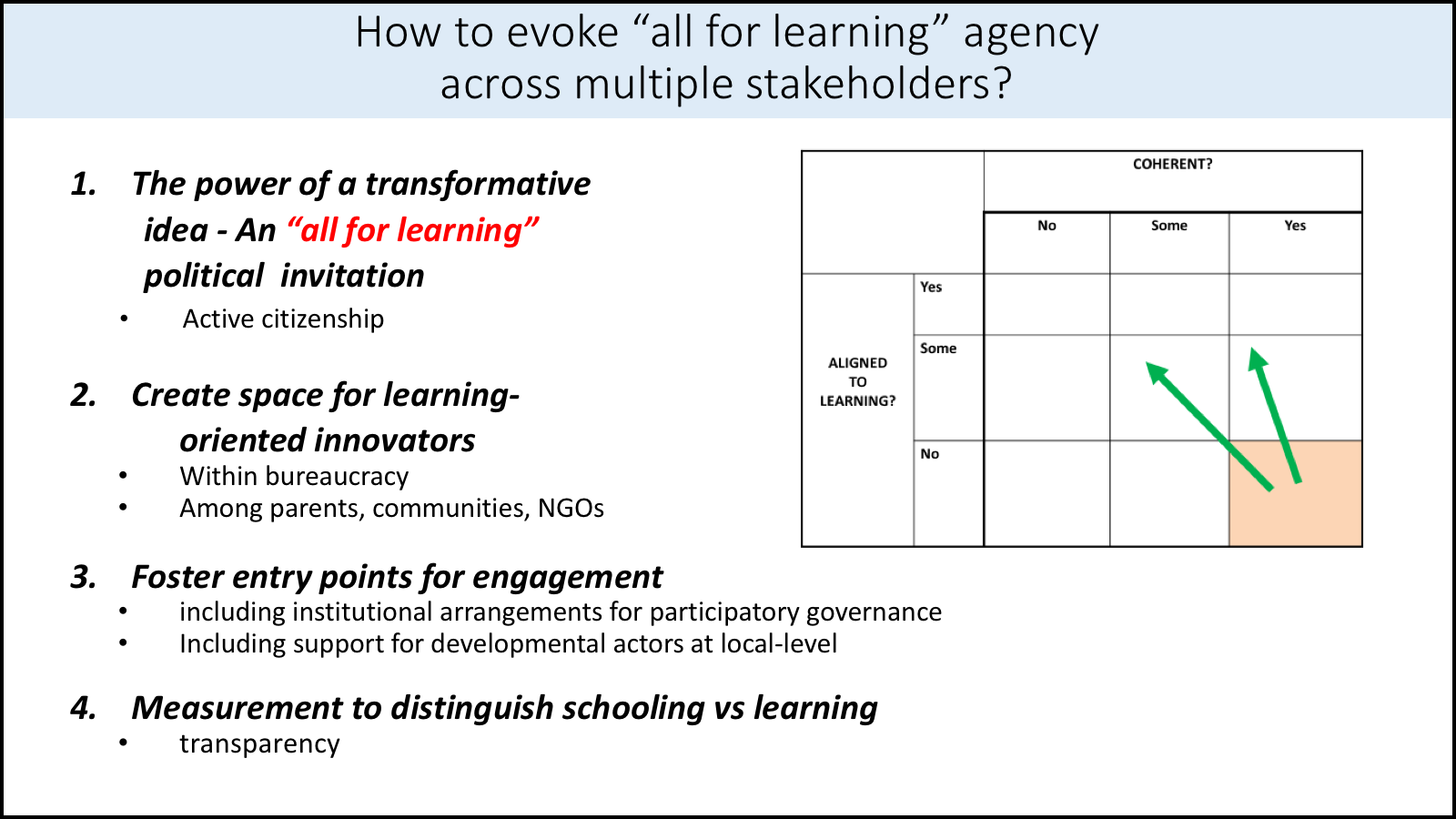

Drawing on the 2018 World Development Report, Levy discussed how to create an “all for learning” environment in these cases (see Figure 2below). His proposals for how to move forward seem possible and plausible, and not only because they map one-to-one onto the four principles of Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA). In order to escape the gravitational pull of the “black hole” of process compliance, one needs to create a political environment that escapes complacency and is driven by a recognition that in locked-in systems, “more of the same” will deliver “more of the same”, and hence, new ideas and new actors need to come into play.

Figure 2. Four steps to creating an “all for learning” environment

This is an important book that everyone working on how to address the learning crisis will profit from, and it was great to have Brian Levy in Oxford to discuss it.

To watch the full presentation by Brian Levy at the Blavatnik School of Government on 8 November, click here.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.