Luis Crouch

RTI International (Emeritus)

Blog

Given the learning crisis, with 600 million children learning much less than is desirable, there is an increased in interest in sharply improving support to countries wishing to move along on the learning and quality agenda.

The World Bank and UNICEF for example focus on foundational learning in the early grades, and especially in reading and mathematics. One of GPE’s three strategic goals is about improved learning.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, wishing to support such entities via the provision of global knowledge public goods, sponsored a workshop on how to use a systems approach to quickly improve foundational learning (FLN) in developing countries.

Actors from three jurisdictions presented their experience: Kenya, the state of Puebla in Mexico, and the municipality of Sobral in Ceará, Brazil. The results are interesting and worth sharing. This blog provides the highlights and a longer note sets out the lessons learned.

These jurisdictions are three of the few that have made systemic and substantial leaps that, if continued and extended, would put them on a trajectory to reach at least the first satisfactory levels in the OECD ranks in a reasonable time.

Few low- or middle-income countries could boast that. Further, the cases are not NGO or donor projects. While they may have had some inspiration from donors and NGOs, they are now at scale and system-wide, largely or altogether using only country-based systems.

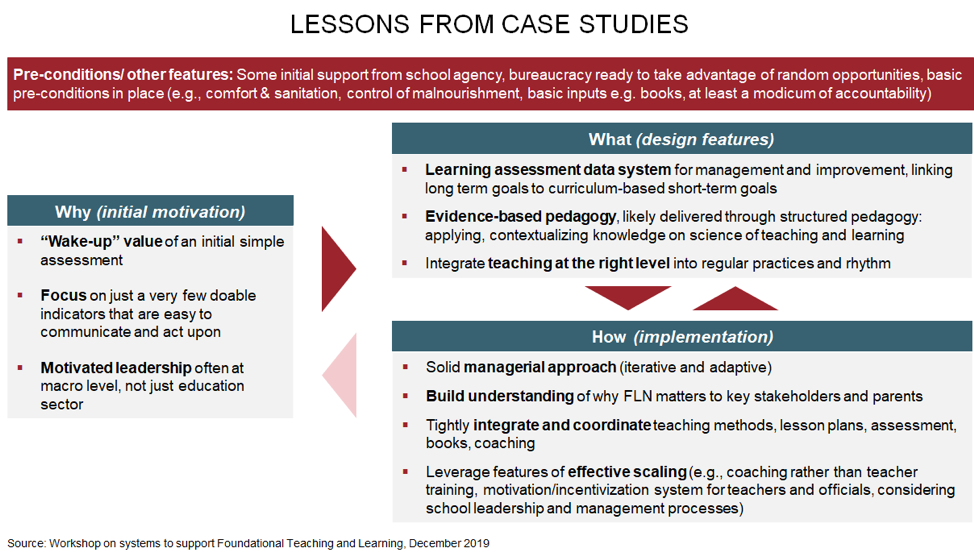

The approach from the three cases is summarized in the graphic below. It is important to note that all three cases had achieved universal enrollment but not 100% completion. Thus, a focus on learning quality were, in these cases, justified by the policy actors in terms of both in helping achieve higher primary school completion but also for their own sake. Since GPE cares about both completion and learning, the experience may be relevant.

The Why phase builds focus on just a few priorities (not more than three if possible) using data that can often have a wake-up value and then also support program design, teaching and monitoring. All three cases focused on learning, two of them foundational from the beginning, one of them starting with secondary but moving to the foundational aspects relatively early on.

The What phase ensures that the key components of an effective learning management approach are in place. A good learning assessment data tool is needed for management and improvement, linking long-term goals to intermediate curriculum-based short-term goals that measure children’s progress in ways that are easy to understand and communicate.

Most importantly, this phase focuses on teaching. This means supporting, via coaching and in-school leadership, the teachers that are already at work, for quick improvement using a clear and evidence-based model that meets the children at their starting place.

Motivation systems are key. Motivation was accomplished in the three cases by relying on the satisfaction of teachers in seeing their children learn (because the advice they are given is based on evidence and works) and professional accountability to their coaches, supervisors and trainers who are delivering advice that works.

The How phase uses a tight management model to ensure that all of the necessary inputs are coordinated, so that the lessons and lesson plans, coaching or teacher support, assessment (formative and summative) and books all go at the same pace and work with each other.

A certain level of prescriptiveness and centralism was seen to help, but only after considerable iteration and adaptation to context. For example, iteration and adaptation in making sure that the lesson plans and the lessons were liked and useable by the teachers. A focus on scaling was programmed from day 1, in terms of cost and do-ability. All efforts involved generating awareness of the issues and the solutions among the key stakeholders.

Tight management also meant concern, in all cases, from the highest level of government (mayor, governor or even president) for significant changes in the sector, often at the beginning of a new period of government. The call on the ministry was for movement on the results but allowed discretion as to the how, and the ministry itself and its stakeholders responded with tightly-managed approaches, after iterating and adapting.

Trust was key in all aspects, but particularly in cementing relationships of professional accountability between teachers and those supporting them as coaches or in-school leaders. Teachers saw that the advice helped. This created respect towards the advisors. Making sure that the advice actually works, by making it evidence-based, was key. Evidence, trust and respect went hand-in-hand and were an effective form of accountability.

The figure makes a key point that spans all: there is some phasing in that the Why, What, and How steps were arrived at approximately that order, conceptually if not chronologically. But in all three cases there was a lot of iterative feedback between phases, especially between the How and the What steps. For example, an adaptive management model (the How) can better discover that lessons are over-specified or under-specified (the What) and act on that information.

This blog was originally posted on the Global Partnership for Education blog on 9 July 2020 and has been cross-posted with permission.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.